Gelen Jeleton, Jesús Arpal Moya, Aimar Arriola, Juan Canela

Tiempo de lectura: 16 minutos

17.04.2017

The Spanish curators and artists reflect on the usefulness of the combination of magic and theory and the spells we must craft to endure a schizophrenic reality.

Juan Canela: Now that 2016 —with all its frightening developments— is almost finished, I don’t think there’s any need to pore over the current situation to agree that the world is not experiencing its finest moment. What do you think? How do you see the general situation and what lies ahead?

Aimar Arriola: Analyses on the “macro” level are abstractions I have no idea how to inhabit. At the University of London, where I’m currently studying and researching, I’ve spent a year attending conferences and debates on “global” matters that I know affect me, but they’re not getting to me in terms of how they’re being posited: “big data,” accelerationism, “the end of the world as we know it” (that was the title of the last talk I attended). Bigger, stronger, faster…like a documentary [of the same title] on culturism and anabolics I saw not long ago. I don’t know how to read the big stuff, I can only read the small things. For example, in this research and archive-production project on the politics of AIDS that I’ve been working on for a few years with my colleagues Nancy and Linda, we say we’re approaching AIDS from “a place where we can read the limits of experience in the present,” which sounds really pompous (and is a statement we’ve got to change right away). [1] But then, in my case, this translates into paying attention to things like why in the AIDS archive there are so many images related to touch or so many representations of birds and ladybugs [words that can have homosexual associations in Spanish]. If for example we’re going to talk about economics, what I want to know is which texts Jesús is reading in the classes he’s currently teaching on feminist economy. Or ask Gelen what you do for a living after writing a thesis past forty, which is where I’m at, too.

JC: I’m in complete agreement with your stepping away from the “macro,” Aimar. Lately I’ve been thinking a lot about how to pay attention to what’s right in front of me. I want to focus on what we don’t see, what we don’t understand, the dark stuff. In how essential it is to accept the impossibility of knowing it all. Allowing for the possibility of not seeing with our eyes, leaving room for the unpredictable, the unknown, the unexpected. I want to face my most absolute doubts with affection and devotion.

“Without light and without eyes one has other ways to (fore)see,” wrote Hélène Cixous.

Jesús Arpal Moya These days I’m reading Amaia Pérez Orozco’s Subversión feminista de la economía (2014) published by Traficantes de Sueños. Right now I’m sitting at the counter at my bookstore, La Caníbal, in Barcelona, surrounded by babies doing a sign language workshop, trying to stay focused as I overhear the wealth of sounds they put out. Christmas is around the corner and the phone will ring and ring, because even in a radical bookstore Christmas rules consumption.

I think there are words for confronting financialization of the economy, “double death,” “necropolitics” (as per Mbembe), “gore capitalism” (see Valencia) and “fascism.” Maybe we’re coming up a little short when it comes to practices and spells to face down the dangers the editors mentioned.

I remember when a trans, racialized author asked me for help distributing an urgent political tract in the independent European press, but they [i.e., the tract’s author, using non-gendered pronouns] needed some kind of compensation to get by. I reached out to a number of people and the big response was, “if the media commissions it, they’ll give the author a euro or two, but if they present it on their own, the media takes that to mean they don’t have to pay.” A spell like that, that gets repeated every day in quotidian situations, strikes me as very harmful and powerful because it manages to cut across everything, underneath the authors we’re citing, the governments of which we may be subjects. So let’s start learning some good little spells and in the quick-time.

AA: I’m writing this in pencil from an international airport, on my way to Bilbao. It’s five in the morning. I ran out of data soon after I got here, so I’m spending the time looking at people and thinking of what Jesús said about the spells that surround us, the ones that get so repeated that they end up creating a reality. I’m not aware of the exact formula of the spells that are active in this airport but their effects are apparent.

One is that almost all the bodies marked as feminine have their legs crossed and everyone else no. The former are listening and the latter are speaking. Another effect is that most of the people that are cleaning and picking up are non-white; unlike the people who are buying things, who are white indeed. A third effect is that no matter how much I stare at people, they don’t look at me. They’re looking at their mobile screens. Sitting around here and there, I see three boys I’d like to stand up and kiss. But there’s another spell that keeps me from doing it.

JC: Just the other day at Donosti we were with Gelen, at a conversation between Amaia Pérez Orozco and Silvia Federici in the context of Feministaldia [2]. There was a lot to think about and discuss. Amaia spoke of the importance of several Latin American female colleagues’ struggles and how they developed an economy rooted in the body-earth space. And someone asked why those female colleagues from Latin America were not on the panel.

I took down some of Federici’s remarks, like: “…there is nothing we can do in isolation…;” “…transform our communities, families and economic structures into resistance spaces…” and “we women do not know who we are, we shall only find ourselves in struggle.”

You’re right, Jesús, we need to learn those incantations and fast. How do we learn them, how do we practice them and what do we want to achieve with them? In the project we’re starting to collaborate on, for Tabakalera in Donosti [3]. I’m asking myself these questions… Can I curate through magic?

Gelen Alcántara Sánchez: I think of self-defensive spells as antidotes to the ones that get implanted, time and again, that guide you and sometimes lead you to get into the game in every life situation, like asking for more because you know they’re going to cut your budget, or when they lie about the deadline without telling you so you’ll deliver on time.

I’m through with conventions, values, things that are obvious.

I don’t want the obvious stuff that keeps you from going into the dark,

don’t want to see what’s in front of me because I long to reach the interior.

I do not want to read more than what I’ve written.

I do not understand more than is already known.

And to answer the question of what you do to make a living after writing a thesis when you’re 40-something —Oh, jeez! Alternative, parasite and queer CVs since we don’t fit in with the official.

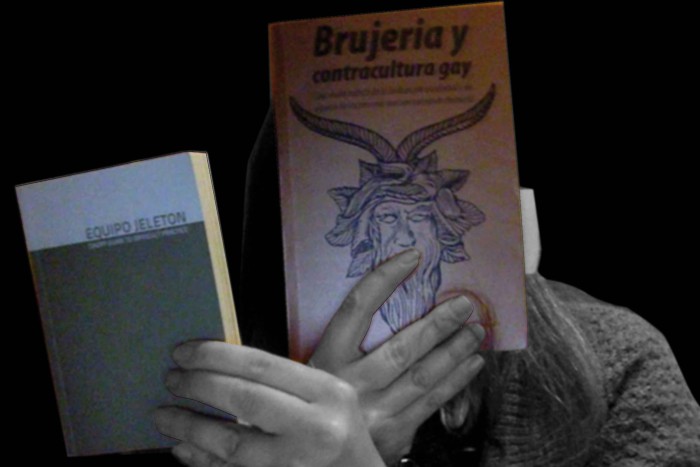

AA: A couple of days ago I revisited Arthur Evans’s Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture (1978). One of the prologues [in the Spanish edition] is by Brigitte Vasallo, which I liked, and it’s been a reminder that I don’t read her enough and I need to read more. I’m left with how powerful the word chusma (i.e., “rabble, riffraff”) is and Vasallo’s invitation to enact a “decolonial history of magic,” to reclaim magic, the magic that informed our aunts’ and grandmothers’ ancient knowledge. And I’m mortified because I can barely remember the spells (esaera-zaharrak) my amama María used to tell me.

Another prologue is the introduction to the clandestine edition Feral Death Coven did in 2013, that interests me because they compare the book to Federici’s Caliban and the Witch (2004), and they appreciate and critique things in both. But I feel like I can’t really offer an opinion on Federici as I confess I haven’t read her book yet.

Another person who went to Donosti to see Federici was my Aunt J, without really knowing who Federici was. I don’t know what she thought but I’m going to ask her. This Christmas she’s been cleaning at my maternal grandfather’s house, going one-by-one through every book or magazine she wanted or needed to let go of, looking at them, touching them, and thinking who they might be good for. Rumpite libros [4] and affective redistribution, I think that’s feminist economy as well.

And connected to the idea of difficulty that’s brought us all here, Jesús and Gelen, what was the title of that little volume that collected the work you two edited in Berlin a few years ago? Wasn’t it something like Manual de una práctica difícil? There have got to be counter-spells there we can use.

JC: I think it’s essential to remember and reclaim those spells our grandmothers had. And related to a few things Gelen was saying —working from the dark, from the margins, from what’s forgotten. Aimar, thinking about your aunt, touching the magazines, it seems to me there’s something about working from the surface that you’re ultimately proposing and that may have to do with all these issues… Can you tell us a bit about how you frame that?

JAM: I finished Amaia Pérez Orozco’s book. It has spells like writing the word production always crossed out. Now I’m reading Miren Etxezarreta’s ¿Para qué sirve (realmente) la economía? (2015).

Our little book is called Equipo Jeleton: short guide to Difficult Practice (2012). I open to a page at random and there’s the poster from the Decora-Chan! 7 action. It was a tee-shirt party; there’s a picture of it. I’m not sure what that’s supposed to be saying to me.

Today is January 1st and I’m in bed writing, with a glass of wine that fortifies me for the task. It’s not easy for me when I’m spending eleven hours a day at the social economy fair. Today is my day off this week. In the living room, I’m listening to D. and M. who are cuddling and giggling. I’m happy because a while ago we and H. were speaking about how to face the risk of being arrested and fined (but surely not deported, because of certain privileges) this year, until a lawyer can resolve their visa issues —we weren’t laughing then.

Regarding the issues you bring up, Juan, they’re tough —I’m not sure. So I’m going to consult two tarot decks I have here in bed: the Sforza Family tarot and the Barcelona “present-soon-to-come” tarot. I wish I could add the Invasorix, but I don’t have it.

How do we learn spells? How do we cast them and what do we want to get out of them? The first two are valid questions, the seeker herself has to answer that third one. I’m dealing two cards from the Sforza tarot:

learn:

two of swords, “a bon droyt,” upside-down:

a tortuous path, a break in dialectic and justice

practice:

king of batons, upside-down: meaningless gestures, eluding strength, chasing old age. “Kill the King” is a children’s game.

Can I use magic to curate?

I can’t see curators doing anything through magic, at most maybe magic could move through curating to bring on changes in the world.

Finally, I’m going to deal a card from the Barcelona “present-soon-to-come” deck, to hit you with a question or frame an enigma for you:

“The Lovers” (the card shows someone at the precise moment of smashing a piñata).

A clue: now I know what the Decora-Chan! 7 image was trying to tell me. There was a piñata at that party in the form of a seven. In the Catholic tradition, it’s the cardinal sins; in others, it’s the magic number.

AA: I’ve had my tarot read two times in my life. Last time N. read the cards in Barcelona, a month and a half ago. The tarot N. uses is the Motherpeace deck, that I wasn’t aware of. They’re these really cute, round cards plus illustrations you wouldn’t believe. The California healer and writer Vicki Noble and the artist Karen Vogel came up with them in the 1970s. To develop them, they researched folklore, art, healing and the spiritual life of ancient civilizations from a feminist perspective. In the Motherpeace tarot, 7 symbolizes inner contemplation. The Motherpeace tarot and Evans’s Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture are strictly contemporary, and are after the same thing: reclaiming positive, pacifist values from pre-patriarchal times. In fact, last night I realized that Jeleton’s Short Guide and Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture share something: both of their “surfaces” make reference to a planetary metal. Witchcraft’s cover is copper-colored; Jeleton’s is gold. I don’t know much about alchemy but Gelen and Jesús know a ton.

On the other hand, I have thought a lot about surfaces this year. What can we understand from superficial practices? I ask myself that question because of the discomfort the words we habitually use to speak of research —dig deeper, penetrate, unearth, drill down— bring on in me. These are words that drag centuries of violence and oppression along with them. The surface is also the umbrella concept under which other issues that interest me reside: the animal question, touch, the garden. For example, Western man has thought of animals and plants as surface bodies, lacking interiority in comparison to the human, who has a soul. For colonizers, racialized bodies also lacked interiors. The depth-surface divide is the central argument that justified, historically, that some people oppressed others. The other day when this straight dude told me not to be superficial, what was he really saying to me? Motherpeace and Witchcraft traffic in a different relationship when it comes to surfaces. For instance, in ancient healing practices, surfaces were important. For the Bribri indigenous people, the surfaces of shamanistic objects were a fundamental part of their symbolic value. Healing started on a surface level. I learned that this summer in Costa Rica when I visited the state collections of pre-Columbian gold —collections also assembled based on violence.

GAS: That reminds me of contact —being touched, wanting to touch someone and how hard that can be at times. Touch as a way of curing, of healing. Not long ago I saw the movies Selena (1997) and Gilda, no me arrepiento de este amor (2016), about two cumbia performers who were venerated as saints. In Gilda, there’s a scene where a woman who was at a concert asks the performer to touch her head, to heal her, since according to that woman Gilda cured her daughter through her music. These touching practices have been associated with the popular, the vulgar and the genteel; when they’re miracles, it comes from Rome, the Pope decides. And you don’t ask a lot of questions, for instance, with doctors and white-coated pharmacists (“don’t ask so many questions,” my mother kept saying to me the last time I went with her to the doctor). It would seem that everything goes through the state-institution required for survival.

Aimar mentioned the book Witchcraft and I think it’s no coincidence that I carried it in my bag while I was at Feministaldia and that I showed Jeleton’s drawing of “finocchio,” that’s in her book where she mentions Evans, to Federici [5]. And that I showed it to Juan before going into the talk. And that Jesús passed it on to me after I gave him Sociología de la imagen (2015), by Silvia Rivera Cusicanqui (whom I’m going to mention here by way of invocation, wishing she were at the panel and hoping she’ll be there next year). And it’s no coincidence that I also have Jeleton’s Difficult Practice with me now, so we can take pictures of them both —but with no flash, as they’re shiny.

Regarding readings, you’ve got to read Federici more —or was it Marx? (it’s a joke).

“You’ve got to read Marx more” is what a friend said to me after Federici and Amaia Pérez Orozco’s conversation. “I have read Marx,” I told him. “What, like all three volumes?” he replied. Ok, I haven’t read all of Federici, or Marx, but I have drawn them. I’ve only got Amaia to go.

There are lots of way to speak and lots of ways to shut people up, casting aspersion on ways of reading or writing. Even not wanting to speak is often speaking —said [seventeenth-century Mexican poet] Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, who, by the way, was a marvelous character who would fit perfectly into Evans’s Joan of Arc chapter in Witchcraft. Let’s think about what we want to say. By chance do we want to repeat the great stories, from the great books, verbatim? What Gloria Anzaldúa calls the mythopoeisis —better said, self-history, or what Audre Lorde called biomythography— is a resistance strategy. Let’s cast spells that do not erase memory, that speak not of a single knowledge and that in their disorder are written in sundry languages, time and again. To return to the problematic of the bad times we’re living through, this sorcery becomes a kind of embodiment of the theory for deciding what we need to hear.

JAM: Today is Epiphany, the Feast of the Magi. The remains of Idrissa Diallo have been located in an unmarked niche in a Barcelona cemetery; Diallo died in a migrant detention center on the night of Epiphany back in 2012.

Closing note: this conversation was created in writing based on a Piratepad collaborative document and was edited on an ODT text file between December 2016 and January 2017, from Barcelona, London, Markina and Murcia.

Notes:

[1] The project entitled Anarchivo sida [AIDS Anarchive], was initiated in 2012-2013 and presented as an exhibi- tion in Spring 2016 at Tabakalera-International Center for Contemporary Culture, Donostia-San Sebastián. e exhibition is scheduled to travel to Madrid, from May to October 2017.

[2] A festival of feminist culture held annually at Donos- tia-|San Sebastián in the Basque country. Begun by the Plata- forma Política de Mujeres Plazandreok, the festival celebrated its eleventh edition in 2016, coordinated by Josebe Iturrioz and Leire San Martín. Activity archive available at https://feministaldia.org

[3] Juan Canela’s project Cale, cale, cale! Caale!!!, chosen for the Tabakalera, Donostia-San Sebastián curator’s residency program. e project “asks what may be the role of magic, ritual and the irrational in relation to nature in

the Anthropocene age” and takes the form of a collective exhibition in which Jeleton will participate (Autumn 2017). [4] Rumpite Libros (2007) was a project by Jeleton involving getting rid of their books. e title makes reference to the phrase rumpite libros, ne corda vestra rumpantur (“break books lest they break your heart”). Aimar Arriola got to know Jeleton’s work on this project.

[5] Finocchio, i.e., “fennel” in Italian, is an insult in that language used to refer to homosexual men, faggots, cocksuckers, fairies; and was an illustration by Jeleton in their project Historia política de las ores that in turn cited work by Federici and Evans. In Caliban and the Witch, Federici mentions how when witches and homosexuals, faggots, cocksuckers and fairies were burned, fennel was used as an aromatic herb to mask the stench of burning esh (p. 271).

Comentarios

No hay comentarios disponibles.