Edición 10.5: ALAC Reader "Soñadores" - California EE.UU. Los Angeles USA

Tiempo de lectura: 6 minutos

01.02.2018

A cross-generational narrative of queer Chicanx and Latinx artists finds a common space in LA.

(Este artículo solo está disponible en inglés.)

I don’t attempt a critique of Pacific Standard Time or the myriad queer Latinx works that will be presented in it. What I offer instead is a personal reflection as a gay Chicano artist who is beginning to be considered an “elder” in the queer community, an identity I am learning to embrace and one that I don’t take for granted.

Over the last several years I have participated in a number of art exhibitions that explore queer and Latinx themes. In most of these, my works from the 1970s, ’80s, or ’90s are positioned as “pioneering” attempts to provide a visual exploration of gay Chicanx or maricón identity often juxtaposed with work by artists born in the 1990s—a younger generation exploring their queer identity. The impulses to create community, to seek out others like us and to visually provoke the hetero dominant cultural assumptions are in both generations’ work. We draw from the same popular culture and ethnic iconography for inspiration. But it seems to me that the advent of social media has allowed younger Latinx artists much larger virtual networks of artistic collaboration and a faster exchange of ideas and access to images. The gay artist circles of my youth seemed to have been smaller and more intimate.

Right now, I realize like never before just how different our paths have been. I assume, as queer Latinx, we align as a community galvanized against a cultural hegemony of white supremacy. Accepting that as a given, it is the wide variety of how we declare queerness in art that I find interesting. Not all queer Latinx art looks alike. But whatever the medium and whether in a public space or a white cube gallery, the prevailing theme for me is always “look at me:” Mírame! Mira! It declares and validates our presence and defies the world to be indifferent. Looking at the art of queer artists over the last couple of years, two things stand out to me: the role of AIDS and its impact on queer Latinx artists of my generation, and how social media shapes the current discourse, networking, and exploration of artistic practice.

The impact of AIDS on my generation left a gap between those that lived through that period and those born just before or shortly after anti-retroviral therapy (ART) was made available in 1996. Death and devastation left its psychological imprint on the older queer and Latino artist community. Post-traumatic stress is a given for those of us who have survived while our homo-social networks got smaller, as artists, friends, lovers, gallery owners, and art patrons died. Collectively, relationships were forged amidst the onslaught and, as a community, we cared and advocated for one another. The anger, grief, fear and loss became subjects in our work, but it was also important to continue declaring our sexuality, our friendships and homo-romance. iMuérdeme! ¡Mírame!

There are four exhibitions that are taking place in California that I would like to use as references to share a little bit of our stories, not just mine but those of my friends and artistic “partners-in-crime” who are no longer here.

In August, as an early start of the Pacific Standard Time, Los Angeles County Museum of Art opened Playing with Fire, a long overdue retrospective of the work of Carlos Almaraz, one of the most prolific and recognized Chicano artists, who died of AIDS in 1989 at the age of forty-eight. His untimely death becomes part of his story. A portion of the exhibition addresses his bisexuality and the internal conflicts about his same gender desire. These conflicts imbued some of his paintings with a queer subtext that provides them with a visual energy and passion that might be missing otherwise. Through a feast of expressionistic animals, body parts, and figures of both sexes (cis-gender male and female) with suggested sexual interplay, these paintings offer us an opportunity to rediscover the difficulty of coming out of the closet and of being honest with yourself in the pursuit of happiness through freedom.

Exhibitions like these were impossible to find when I was young. There were no spaces where you could find yourself represented as a queer Chicanx. I recently gave a tour to Latinx students in their teens and twenties of the exhibition ¡Mírame! Queer Latinx Expressions at La Plaza de Cultura y Artes, curated by Erendina Delgadillo, who has indicated that artists were selected specifically to reflect the “evolution in the arts community in both message and medium.” Works by Alma Lopez, Laura Aguilar, myself, and Hector Silva anchor one end as older artists, alongside the work of younger artists like Ben Guila, Julio Salgado, Yosimar Reyes, and Xandra Ibarra. Overlapping explorations of immigration, racism, and deconstructed gender identities intersect with queerness without hesitation. Senadores, undocumented youth, cholos, and Mexican iconography blend together proudly. Where Almaraz struggled to resolve his identity as “Chicano” and to come to terms with his same gender desire, here the queer subtext is both intergenerational, front-and-center, and, in some cases, quite literal. This exhibition works then as a space of recognition that assures integration to a young generation.

A third exhibition, Axis Mundo, is split between MOCA PDC and the ONE Institute. It chronicles queer Chicano Networks in LA over the course of three decades from the 1960s to the 1990s, and features the work of Mundo Meza, who died in 1985. His paintings, drawings, costumes, and displays are represented as an “axis mundi” or central pillar from which pivot various networks of queer Latinx artistry, ranging from performance, fashion, design, painting, punk music, mail art, and AIDS advocacy. Included is the work of Jef Huereque, Teddy Sandoval (d. 1995), Jack Vargas (d. 1995), and Ray Navarro (d. 1990). With Meza as “axis mundi,” it documents our queer artistic collaborations when a Chicano avant-garde in LA was emerging. With this exhibition more than any other, Pacific Standard Time starts to bridge the gap between queer Latinx generations. Míranos!

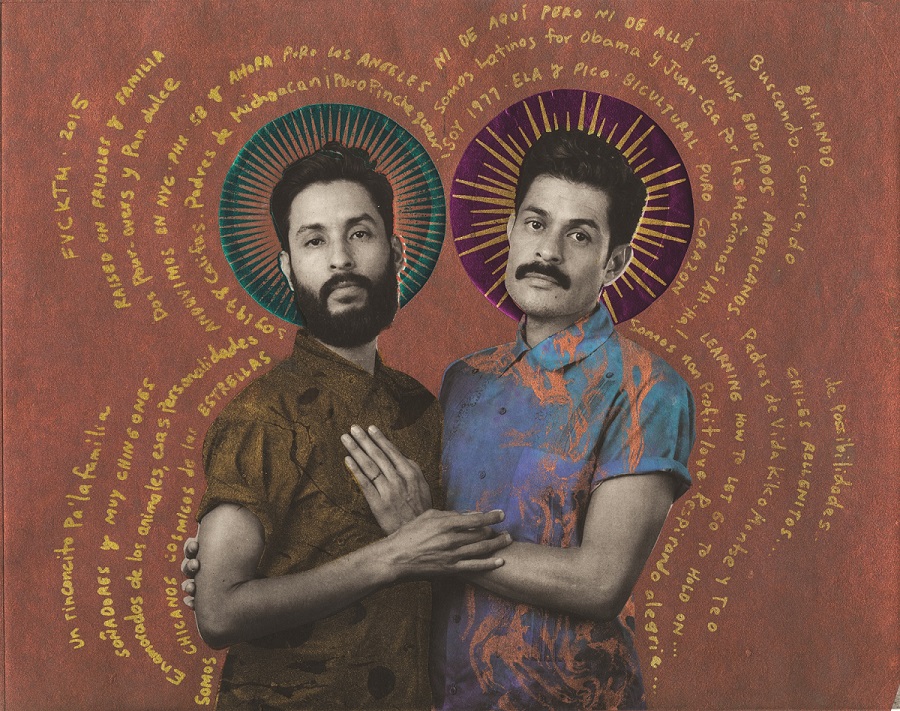

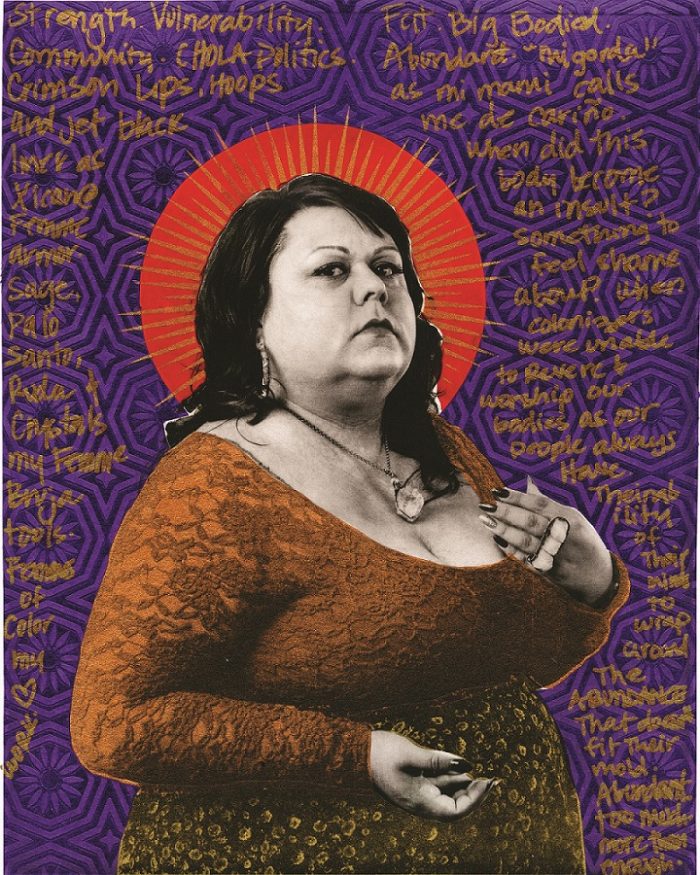

As Gabriel Garcia Roman explains, there is an ugent need for inserting our queer Chicanx stories and narratives out into a world that benefits white hetero-normativity. His work is currently featured in the exhibit Queerly Tehuantin at Galeria de La Raza in the Mission District in San Francisco. At forty-four, he is closer to my generation, and like me he chooses to borrow from the religious iconography of his Catholic upbringing as a starting point for creating beautiful portraits. Russian icons are his trope of choice, which he takes and re-engages by featuring friends and acquaintances with shimmering haloes and incorporating written text. I believe by replacing the faces of saints with portraits of Latinx advocates he bestows them with a secular holiness, recognizing them as “saints” within the Latinx community, a gesture that recognizes the sacrifices they have made for freedom and recognition.

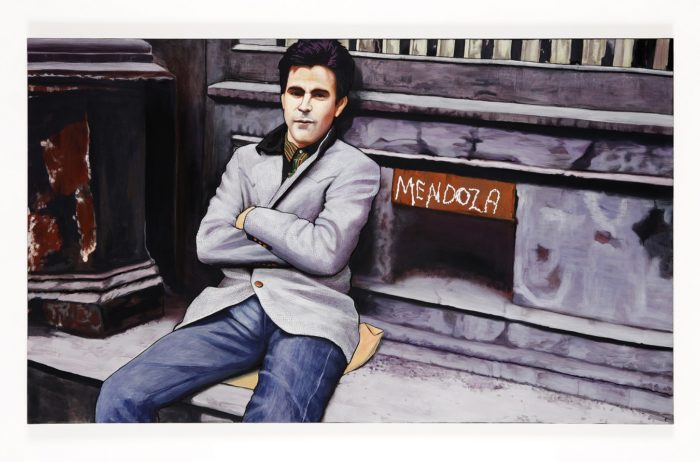

Like Meza, Gabriel’s artistic productions are collaborations that visualize diversity within our community. Gabriel states that through his icon portraits he wants “to push the narrative further by having the subject write about their identity around their portrait.” He amplifies their voice by adding a screenprint of handwritten texts that spoke of their identity around their image inviting them to embrace themselves proudly. In each work the individuals literally proclaim their identity. Under the rubric of “queer Latinx” those declarations link his work to mine thematically, yet our strategies for creating work couldn’t be more different. In the ’70s when I started exploring the dual identities of being Chicano and “gay” the work was about where they intersected but also where they clashed which became the impetus for my art. Under the prevailing feminist mantra of the “personal is political,” I proudly declared myself maricón, but also made confessional work about sexual dysfunction and romantic heartbreak. Calling myself Homeboy Beautiful, I called out racism in the gay white male community but also critiqued the machismo and self- loathing in the Chicanos and homeboys I knew. I used satire and visually borrowed from comic strips and novelas. My intent was to create a Chicano homo “space” (in popular culture) where we could declare and reveal all.

Comentarios

No hay comentarios disponibles.