23.10.2020

“Can the 11th Berlin Biennale be a weapon?”

Arpilleras; Unidentified women artist, [Untitled], ca. 1973–1985. Pieces of fabric sewn together (arpillera). All works Collection Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA), Chile. 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9. – 1.11.2020. Photo by Mathias Völzke. Image courtesy of Berlin Biennale

In mid-2019, when the activities for the eleventh Berlin Biennale (BB) had begun with a series of lectures and workshops at ExRotaprint (an independent, community-led project space located in the northeast section of the city), the particular character of this edition of the Bienal became evident. Alongside the production of a major exhibition, the curators’ interests—those of María Berríos, Renata Cervetto, Lisette Lagnado, and Agustín Pérez Rubio—also lay in the mediation of works related to issues faced by vulnerable collectives from the global South. To this end, they planned a series of workshops and lectures that involved both participating artists and a diverse range of local actors and projects. Although the process was interrupted by the implementation of pandemic containment sanitation measures, the Biennale’s last phase—an expository epilogue comprising five curatorial sections—was finally carried out and inaugurated at the beginning of September 2020.

However, after walking through the exhibition, the one apprehension we are left with is just how effectively the BB was able to bring us into dialogue with the conflicts and aesthetics of the global North and South. Despite our Latin American backgrounds and origins, our main impression was that of watching a series of realities that, although known, were quite alien, isolated, and, in a certain way, removed from the Berliner context. Rather than establishing a profound connection, an “empathy,” or a questioning of our own convictions, the sensation was that of zapping through conflicts. Why did this effect come to be? Why did an exhibition that questioned a patriarchal system, the censorship of bodies, or the persistence of colonial relations result so alien and tepid? Did the BB lack strategies for confronting us intensely with North-South relations?

Perhaps this event’s real contribution lay in our preoccupation with empathy and the connection with these issues. Below, we will briefly present some intersections and experiences in relation to new forms of solidarity and decolonial feminisms present in the BB, that thus provide guidelines for rethinking our perception of a contemporary artistic activism.

Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA), Installation view (detail), 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9.–1.11.2020. Photo by Mathias Völzke. Image courtesy of Berlin Biennale

New solidarities

One of the thematic cornerstones of the BB is “The Inverted Museum,” that, among other things, questions the cultural and power relations between North and South as seen through the traffic of archaeological objects, the extraction of natural resources, and the repression of ancestral cosmologies. Additionally, this theme characterizes the South as the site of great projects of solidarity and resistance that continue to be present. With the phrase “Can a museum be a weapon?,” taken from the founding of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in 1974, the BB presents us with a magnificent cultural project of the circulation of significations at a continental and international level, in favor of the defense of democracy. The collection of posters, drawings, and screenprints by artists such as Beatriz Gonxález, Taller 4 Rojo, the fabric mural by Gracia Barrios/the “Arpilleras” (with handiwork sewn by Chilean women during the military dictatorship), evoke a certain nostalgia related to popular struggle and resistance. A nostalgia that intensifies when we remember the recent movements in Chile, Colombia, Haiti, Hong Kong, Iran, and Lebanon, that oppose political regimes and unmeasured neolibieral economic projects. A nostalgia also related to the difficulty of thinking of contemporary solidarity as project equivalent to that of the seventies, that is, one that is massive and borderless in scope.

“The Inverted Museum” pushes us to rethink our idea of solidarity when we examine it in relation to the other themes of the BB. We should ask ourselves, then, how exactly could solidarity be manifested in a context that is decolonial, anti-patriarchal, anticlerical, and inclusive of dissident bodies. The question here is for solidarity at a small scale that involves vulnerable collectives that have been violated, marginalized, and that have recently reclaimed their space in the field of global cultural production. In this sense, these new solidarities appear represented under the shape of a natural metaphor, as something living or organic. Servicio de escuchación, by Osías Yanov and the collective Sirenes Errantes, presents another picture of solidarity that alludes to a natural element (in this case, salt) that, due to its physical properties, tends to group together. In this manner, they established a network of salt artists and listeners that has remained active since the beginning of the pandemic. At the same time, we can observe alternatives to patriarchal violences in the works of Marwa Arsianos, part of the series Who is Afraid of Ideology? that documents through video the resistance of women communities, amongst them one in Colombia that specifically fights for land rights and the defense of seeds. The conflicts revised in this work revolve around a living element and on top of the network that is built to protect it. Can the museum located in the North become a space for vital sensibility when, historically, its founding and sustenance is based on the plundering of life?

To continue this line of thought, we could then ask: “Can the 11th Berlin Biennale be a weapon?” Unfortunately, this would be an erroneous assertion. There is a poor actual fomentation of networks or significant circulations between the North and South. In its place, we think that the BB could have favored spaces that relocated the passivity of observing visitors, and so exposing the co-responsibilities that exist in the preservation of conflicts from the North. Here is the final twist of the screw that this epilogue lacks and clearly accentuates the marked distance that we, as viewers, experience with the works they present.

Bartolina Xixa, Ramita Seca, La Colonialidad Permanente [Dry Twig, The Permanent Coloniality], 2019. HD video, color, sound, 5'07". Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale, Gropius Bau, 5.9. – 1.11.2020. Photo by Mathias Völzke. Image courtesy of Bartolina Xixa & Berlin Biennale

Decolonial Feminism

Another one of the curatorial themes of the BB was “The Anti-Church,” a selection of objects that questioned the patriarchal system, that is, symbolic and binary structures established for the control of bodies and identities at the ethnic, sexual, national, linguistic, religious, economic, and even political levels. Here, we are interested in highlighting the proximity of some of the works with imaginaries of decolonial feminism, as stemming from the intersection of said structures with systems imposed through the colony and contemporary issues.

In this context, some of the artist revindicate the leadership of indigenous women. Through their exploration of these figures, the artists go beyond recuperating their historical role to reactivate an ancestral knowledge and spirituality associated with “Mother Earth” as a form of resistance. In this case, feminist struggles transcend the common ground of fight for gender equality and connect with land defense, “Mother Earth,” and denouncing extractivism in its widest sense, natural resources as well as bodies and significations. Ramita Seca, La Colonialidad Permanente is a performance that reinterprets the struggle of Bolivian heroine Bartolina Sisa, who led a rebellion against the Spanish colonial system in the mid-eighteenth century. The performance is carried out in the middle of a dumpster, where the andinx drag persona of “Bartolina Xixa” sings and dances to the rhythm of a song with folkloric roots that denounces the current impact of big corporations on the environment and the vulnerability of women, children, and indigenous communities in the global South. Something similar happens in Resilencia Tlacuache by Mexican artist Naomi Rincón Gallardo, a video that references for mythical mesoamerican characters, whom, in the middle of a ritual, denounce the losses that come from the extraction and elimination of natural resources in a territory. The video is also an homage to Rosalinda Dionisio Sánchez, who had spearheaded the resistance movement against mining in San José del Progreso in Oaxaca, Mexico.

Let us now return to the North, where the Biennale takes place, and let us truly interrogate the resonance of these works in this specific latitude. To what extent do these result as purely hermetic, autorreferencial, and homogenizing forces for the experiences of violence as ived by women, trans* people, and dissident sexualities? These are questions that take us, once again, to a binary position, to those old issues related with the exotization of the South and clichés. Here, the curatorship’s opposition to established structures remains somewhat incomplete, or, put in other words, the significations of the periphery remain in the periphery, leaving a gap with the North open and covering the cultural differences that we need to transcend.

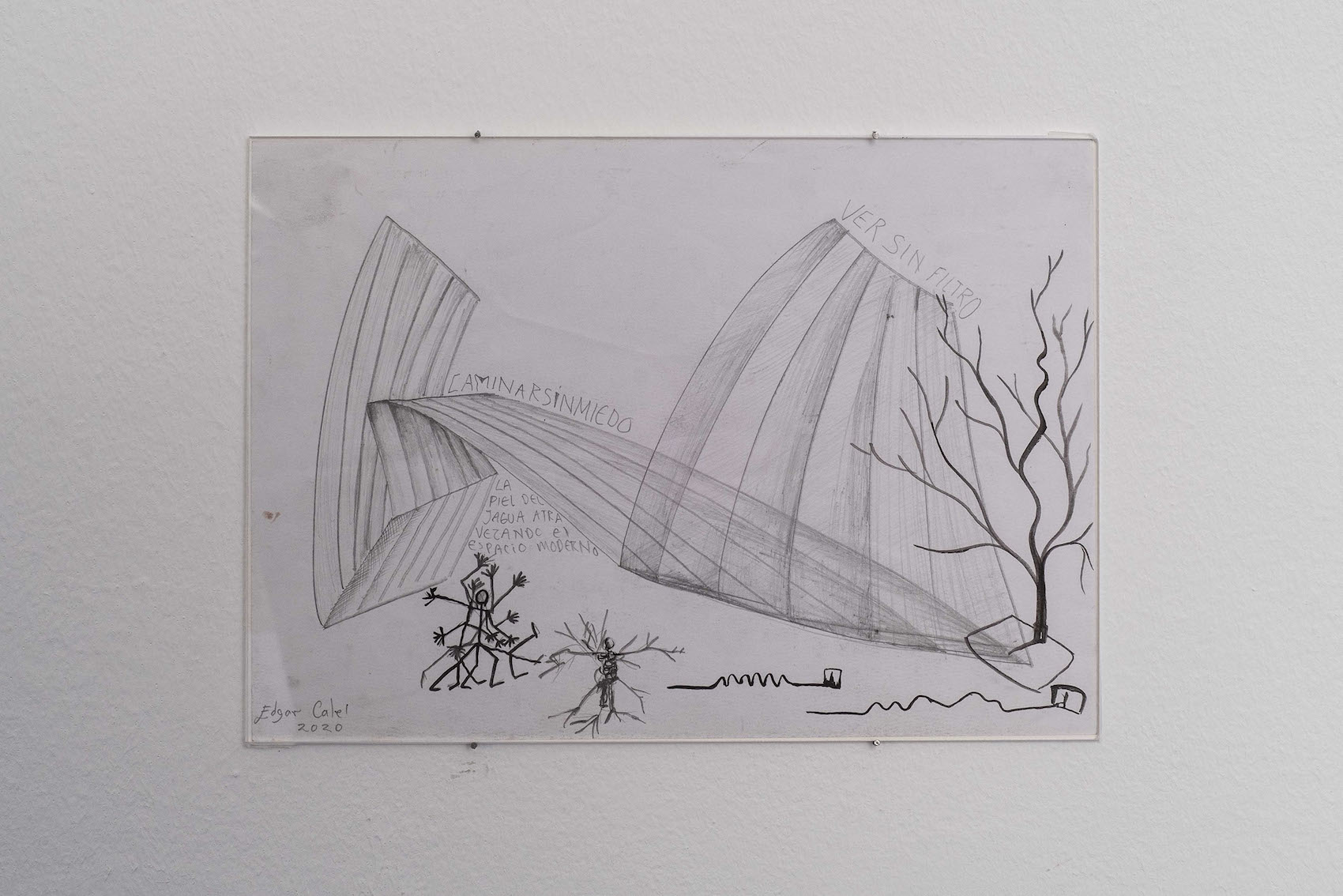

Edgar Calel, from the series Ni Ch’itiloj Ri q’aq [Phonemes of Fire], 2020 – ongoing. Charcoal, pencil, pen and India ink on paper. Installation view, 11th Berlin Biennale c/o ExRotaprint, 5.9. – 1.11.2020. Photo by Mathias Völzke. Image courtesy Edgar Calel

Denaturalized activism

The ways in which the activisms, complaints, and issues raised by the artists of the South in the North have been presented seems to have denaturalized or alienated such activisms as we know them. Going beyond an evasion of the political, something that other articles have raised, this activism results as very strange in the North when it is accompanied by works charged with mysticism, that in certain moments and throughout the exhibition, are perceived as formulas for conflict representation that fail to articulate themselves within the context. We could say that this alienation has robbed these works of an important critical character necessary for activating or provoking the public to mobilize in some way in relation to the conflicts, roots, and factors that come into play in the continuity of these issues in the global South.

Nonetheless, the reference to new solidarities, as well as decolonial feminism, can be experimented in other sections of the Bienal; “The Living Archive” in ExRotraprint, the place for the experience and development of these processes. As was planned from the start, here is where artistic activism is brought together through a living, growing space in regards to the tension between objects and subjects. Likewise, here is where the binary was broken through artistic practice, where expressions between performing arts (theatre, dance, and music) were combined with literature and visual arts. This space demonstrates the importance of working collectively, of activating collaborative processes that oppose themselves to unique systems, to solitary processes; that, on the other hand, can have a home base in micro-resistances, as a path for joining and establishing a working network that is not reduced to the temporality of the BB.

Together But Unstirred, the title of this review, refers to a great quantity of isolated agents reclaiming and fighting against concrete issues. It also refers to the lack of complicity that existed between the artists and the public in this biennale. While some denounced and continue to actively resist, others observed them passively. Perhaps if the works could have been accompanied by these processes, the reception and conflicts would have been others. Everyone together in Berlin but everyone looking their own way, their empathy unstirred.

Las cinco secciones son: La grieta comienza dentro, La anti-iglesia, Vitrina de cuerpos disidentes, El museo invertido y El archivo viviente. Para más información acceder al website de la bienal: https://11.berlinbiennale.de/

Comments

There are no coments available.