04.08.2022

The representation and participation of the Global South at the Venice Biennale serves as a starting point for the reflection that Tania Adam Mogen constructs: the possibility of works that tighten the rules of the game and blur the boundaries between art, politics and radical imagination.

First of all, I have never set foot in the Venice Biennale—in fact, I have never been to Venice—, so this reflection is not meant to examine the artistic proposals of the pavilions and exhibitions, nor is it another criticism of its curator, Cecilia Alemani. I am writing this text because I am interested in talking about the constant uproar and indignation raised by many of the works coming from the Global South and its diasporas in the art world, to the point of questioning whether if what they present is art. The discomfort and offensiveness of Western curators and art critics dealing with projects that seek to change the rules of the game by representing otherness, questioning or examining the current world order from the South is always surprising. Works that at least try to provide meta-narratives and push the boundaries of art critically and from multiple perspectives, blurring the boundaries between art and politics, between art and survival.

Historically, women, black and indigenous people or, in general, those from the Global South have been relegated to the margins; now, their incorporation into the art system with their visions and histories is disturbing, and their recognition is more questioned than celebrated. Nevertheless, we are living in a moment of transformation and symbolic transfers of power; in the coming years, the focus will continue to be placed on subalternity, rewarding not only their work but everything that constitutes them, because epistemic diversity is already a contemporary condition. The reluctance to accept these new configurations in art only reaffirms the end of the monopoly of the Western canon that insists on the existence of a common, objective or eternal truth that determines everything. The blessing of this canon, Harold Bloom style, is a factory of reactionary positions and the constant annulment of black, indigenous, southern, queer, feminist art or any culture of the “subjugated”.

Unfortunately, this culture of cancellation is systemic and endemic, and has been going on for decades. In 1992, two years before Bloom published The Western Canon, Stuart Hall, in his text The West and the Rest: Discourse and Power, described perfectly how cultural hierarchies are also based on power relations; furthermore, Hall warned that “the West” is an idea, a concept, not just a geographical location. An idea that represents a verbal and visual language, turning it into a term that functions as part of a system of representation that provides evaluation criteria and a mode of comparison that helps to explain the difference. Similarly, “the Rest”, represented by the South, is a state of mind, a way of conceiving realities, often antagonistic, often perceived with distrust and contempt.

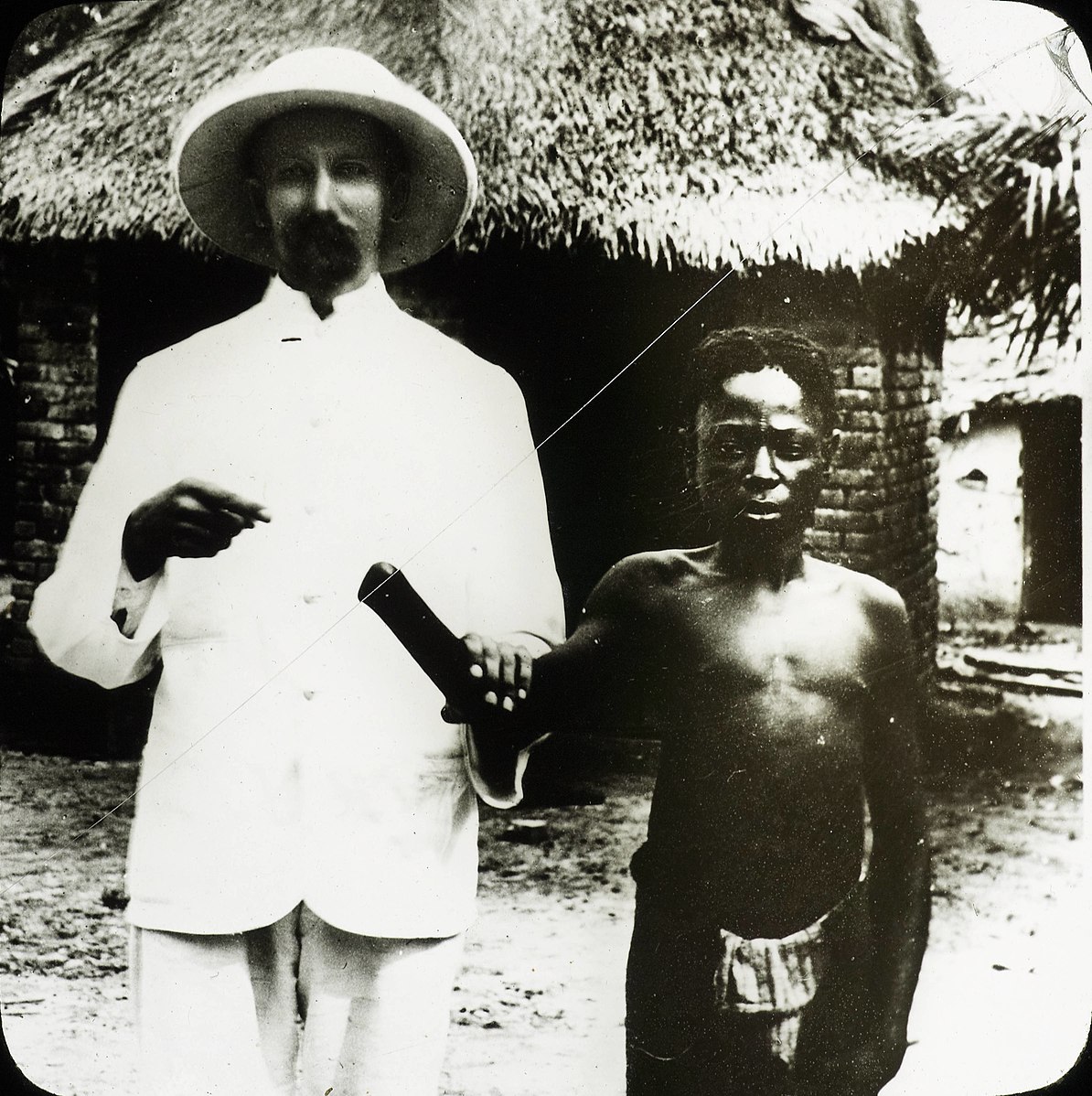

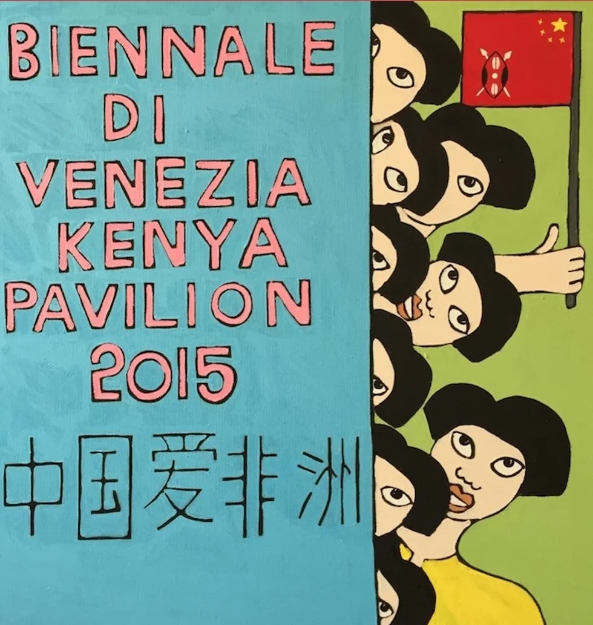

We are immersed in one of the most relevant cultural disputes of the 21st century, and the Biennalle embodies all that visceral vehemence against otherness, as well as the power games of the West. This space of both art and geopolitics, which is created under the bases of hierarchization, the logic of nations, modern states and the values that sustain it, is undoubtedly the place where culture wars and the multidimensional crisis of the nation-state are evidenced. But it is also a space of colonial amnesia. It would be good to remember the hypocrisy and whitewashing of the West in the Biennial, since it cannot be overlooked that, in 1875, ten years after the Berlin Conference, in which most of the colonial powers that would sit at the negotiating table to divide up the African continent, the I Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte della Città di Venezi took place—the precedent of the Biennial in which Europe exhibited its economic and political potential. Years later, in 1895, when the Bienalle Foundation was officially founded, countries such as Belgium, Germany, Great Britain, France and Holland were building their own pavilions at Il Giardineto, while committing atrocities in their colonial territories. In the Congo Free State, a colony under the personal rule of King Leopold II of Belgium, the genocide of ten million people for the exploitation of rubber was taking place; the British South Africa Company, created under the command of Cecil Rhodes, was founding in his honor the territory of Rhodesia in southern Africa (now Zimbabwe and Zambia), while facing the first Chimurenga revolution and establishing the foundations of the Apartheid regime; and Spain, still without a pavilion, participated in its first Biennial smelling of gunpowder from the war in Cuba and drunk on the atrocities with the populations of Equatorial Guinea to establish its future colony. Meanwhile, in 1909, Germany inaugurated its brand-new pavilion after carrying out what is considered the first genocide of the 20th century in Namibia, for which it recently announced reparations for the systematic mistreatment, rapes, beatings and executions of the Herero and Nama population. This double life the Western countries live has been a constant: on the one hand, they exhibit art; on the other, they perpetuate the violence that enables them to maintain their power.

I understand that, for many critics, historical memory is fortuitous, and point out, for example, that when, in 1930, the United States inaugurated its first pavilion in Venice, black inhabitants were still being lynched in their cities governed by the segregationist Jim Crow law. Or that in 1967, when Simone Leigh, this year’s Golden Lion, was born, African-Americans had only had the right to vote for two years. The fact that Leigh is the first black woman to represent her country on her own merits has a great symbolic value, because this recognition enters the realm of the emblematic, where the weight of colonialism, racism or the oppressions of the diasporas are values on the rise. And those who find it hard to understand, are not understanding to what extent the symbolic order of postcolonial society is operating.

When, in 2002, Documenta 11 awarded the artistic direction to a “non-European” for the first time, one could suspect that something was going on. The mere fact that the director Okwui Enwezor was Nigerian raised expectations. Enwezor then seized the opportunity to produce a postcolonial exhibition and send the signal that the complex world we live in demands a complex form of (artistic) engagement, not an autonomous, narcissistic art world. Fourteen years later, Documenta 14 opened up to the South, a position shown in his publication South as State of Mind, where he explored issues such as the masking of identity and the silencing of dissidence, orality and recognition, indigeneity and exile, provenance and repatriation, or colonial and gender violence. A trail that is reinforced at Documenta 15 with the collective of artists and creatives from Jakarta, ruangrupa. All these approaches to the South show that in this bienalization of art there is a need to embrace the world from a broader and more complex perspective. However, their task is ambiguous, since they do not let us glimpse if it is due to an exhaustion of the linearity of the history of Western art that has been absorbed under the white and privileged prism; or if it is due to the impossibility of moving forward as humanity without introducing the thought that has been buried until now. Or both.

In any case, in the attempt to overcome stereotyped oppositions such as north-south, center-periphery, or “developed”-“primitive”, the turn of the tables is a path of light and shadow, because, on the one hand, it is problematic that, in these adhesions, simplification, non-problematization, depoliticization and trivialization of the whole complex and crucial universe for the understanding of our world prevails. And on the other hand, because the old world order resists. It is paradigmatic how in the Venice Biennial the participation of the countries of the South is intermittent and they tend to participate under the logic of the national pavilions without politically problematizing their position. Finally, the rebalancing of power proposed by Cecilia Alemani must be questioned. It is true that both Simone Leigh and Sonia Boyce, the winners of this edition, are two black women, but they represent two major Western powers, the United States and the United Kingdom, respectively. And this small detail cannot go unnoticed when we talk about the confrontation between the “West and the Rest”.

Comments

There are no coments available.