11.08.2022

Curator Helena Lugo talks to Daniel Godínez Nivón, who represents Mexico at the 23rd Milan Triennale.

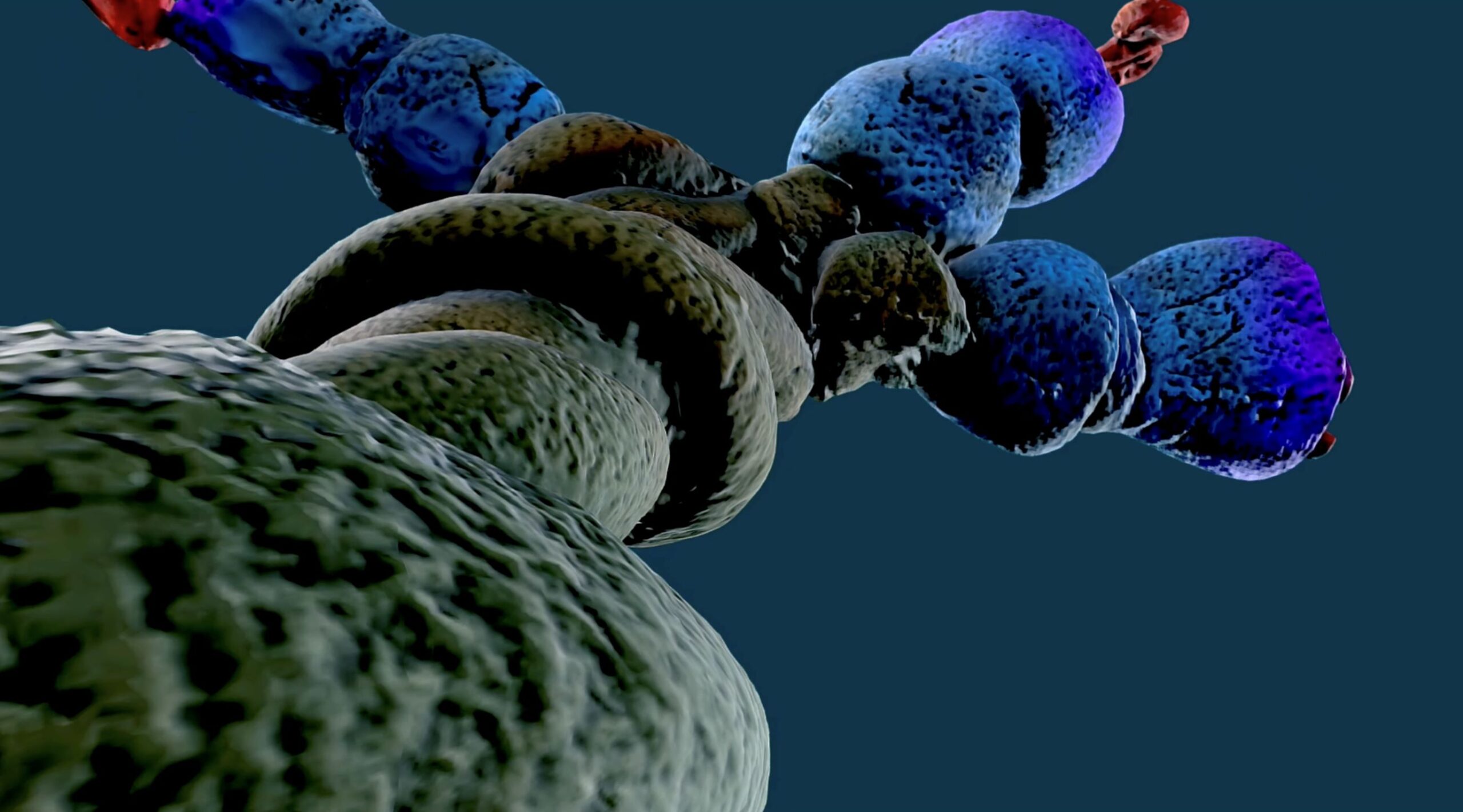

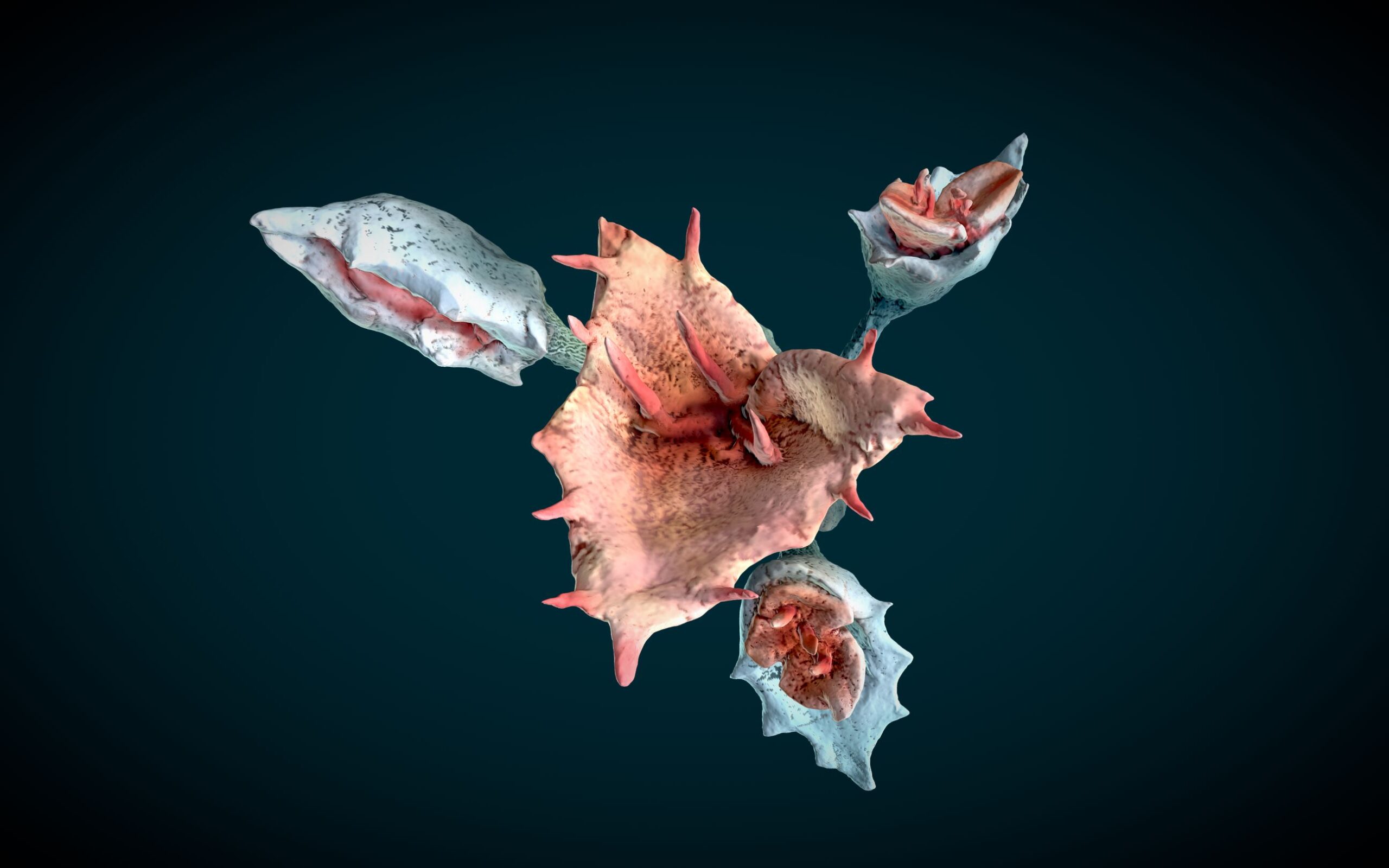

Ensayo de Flora Onírica is a project by Daniel Godínez Nivón that gathers a series of flowers and plants that a group of girls discovered while they were sleeping, from a workshop where they explored the possibility of sharing and meeting each other in dreams. These dreamlike encounters began to be filled with fantastic species of flora which led to the realization of a botanical study in collaboration with illustrators and scientists from the Faculty of Sciences of the UNAM. The study consists of a series of diagrams of fantastic flowers that come to life through 3D modeling and animation. The Ensayo consists of materializing a landscape from the girls’ dreams, a scientific look from botany and a speculative artistic research that reflected on the evolutionary process of these new species.

Helena Lugo: Ensayo de Flora Onírica is a project that brings together the dreams of the girls from Casa Hogar Yolia, creating a collective imaginary landscape and a scientific study of flowers that do not exist. Can you tell us how the project came about and why you chose to work with this specific community?

Daniel Godinez Nivón: My relationship with Casa Hogar Yolia arose in 2015, following an invitation from curator Jessica Berlanga Taylor, who at the time coordinated the Zonas Liminales project at the now defunct Fundación Alumnos 47. They had been working with the girls for four years, conducting workshops that sought to provide an approach to creative thinking and diverse artistic practices. Workshops were held on corporal expression, science, film appreciation and video, among others. In response to this invitation, I decided to link the teachings and lessons I had learned while collaborating with women and midwives from the Triqui community of San Juan Copala, residents of Mexico City, whom I met during the realization of a previous project called Tequiografías, carried out in conjunction with the Asamblea de Migrantes Indígenas(AMI).These women dedicated to birth use dreams as a space of knowledge with repercussions in both personal and collective life. It was very important for me to be a bridge between these powerful women and the teenage girls at Casa Hogar Yolia.

HL: So this process of sharing and meeting others in dreams, did it come from midwives of San Juan Copala? One of the most pressing questions that comes to me is: how did the girls start dreaming simultaneously botanical motifs? Is it really possible to generate a collective landscape from something as personal and abstract as a dream?

DGN: It was just all part of a process. When I started working with the girls I proposed a workshop entitled Propedéutico Onírico (2015-2017), which consisted of the collective creation of a work of art based on dreams. The goal was to meet twice a week: on Sundays we would meet at Yolia to draw, tell each other our dreams, meditate, read and write poetry; while our second meeting was meant to happen in a collective dream every Wednesday at three in the morning. From the beginning my intention was to hold assemblies in dreams, an idea that little by little was transformed.

The methodology of the project is inspired by an action-research approach. For months we worked on our intention to meet in dreams, we made drawings of the place where we would like to meet, we chose phrases to say before going to sleep, we even created a pillow to use only for our Wednesday date. We tried to meet in our dreams for six months without being able to meet completely; after six months of trying, plants and flowers began to appear in our dreams. First appeared the scent of chamomile, ferns growing in our hair and a palm tree that gave shelter to one of the girls. As the months went by, more plants appeared and some of them became stranger and stranger.

HL: How was your process of collecting dreams? Dreams are an unknown and part of very personal world that is usually shared orally, almost impossible to transmit visually. Why did you decide to generate visual material from such an abstract source and, above all, how was such a specific landscape generated from having such diverse visions?

DGN: Relating a dream implies a first level of translation, even as we review in our mind the experiences we had in the dream, scenes begin to appear mixed with emotions and sensations that we did not have when we woke up. This is why dreaming is a practice that is encouraged and developed throughout life. Keeping a dream diary is a good approach to recognize the experiences we have when we sleep.

As a visual artist, I use drawing as a means of grounding thought. It is a tool that allows me, in a very immediate way, to document experiences, sensations, memories and dreams. An organic journey in the work process during the Propedéutico Onírico was to move from orality to drawing, in order to get to know more about the plants that appeared in our dreams. From the beginning we started a diary in which we recorded our dreams on a daily basis. This record was totally personal and only the dreamers had access to it; the only day we shared dreams was on Sundays, to corroborate if we had managed to meet the previous Wednesday in the collective dream.

During the months of work, and as we had more and more strange plants, we began to explore various forms of representation; for example, we began to model their shapes with gestures in the air, to make representations in clay, as well as to scan with a Kinect our bodies imitating their shapes.

At the end of the project, we made a garden of mud and ash from the Popocatepetl and placed it on Iztaccihuatl at 4280 meters above sea level. Due to its material characteristics, each plant is made to last an average of 5 thousand years, so that little by little the dreamed garden is integrated to the “sleeping woman”. You can visit the garden of dreamed plants in the Parque Nacional Izta-Popo, very close to La Joyita.

HL: The final images were made in conjunction with a series of scientists from UNAM, could you expand on this relationship that was generated between the girls’ unconscious and the positivist—though also imaginative—knowledge that the scientists had to go through in order to visually materialize this imagined landscape? How were the relationships between botany, your artistic process and the girls’ dreams interwoven? Why does the final result take the form of 3D images?

DGN: At the end of two years of work in the Propedéutico Onírico, we had a series of drawings and records of plants that we did not know if they existed. This question led me to visit the Faculty of Sciences of the UNAM to talk to and get advice from biologists and botanists. I had the good fortune to present the drawings to a group of teachers, to whom I said: “these plants were found in dreams, but we don’t know if they exist; maybe you can help us recognize them”. They looked at them carefully and said: “these plants are new to us; we should study them”.

It would be a study in which we would not only create the scientific illustration of each of the plants, but we would also have to imagine how they would evolve: what would be the shape of the oldest ancestor of each one of them? What would they be like in 50 thousand years? What is the relationship between plants in the territory of dreams? What is photosynthesis like in a dream?

The process began by showing drawings of each of the plants to the scientists, who began to find possible families to which this plant could belong. With this, the need arose to generate more detailed models with the physical characteristics that these plants might have: the thickness of the petals of some flowers, the amount of pollen they might have, the size of the thorns of others, as well as the appearance of their roots.

3D models and holographic projection are means that allowed me to answer an important question for this project: how can I materialize a dream? The digital resources allowed me to work in greater detail on the external aspect of the plants, as well as to go through their internal structure.

HL: Can you tell us a more about these speculative processes? Tracing the pasts of these flowers—their ancestors—and imagining the relationship to dreams, was this a process that continued to include the girls or was it more your artistic process? What do the girls think of these 3D modeling flowers?

DGN: In the dreamed flora, it is possible to identify traits that can be associated with certain plant families, as well as characteristics that reveal some mutations during their evolution. Together with scientists, we imagine and draw the routes they followed since the emergence of the first unicellular microalgae that inhabited the oceans about 1.6 billion years ago.

The girls are part of the process, fascinated by some of the features of the 3D models of their dream plants. In particular, they are very attracted by the possibility of seeing and touring their plants inside. Another aspect is the sound design of the animations, which was derived from the dream descriptions and the collaboration with Mexican sound artist Fernando Vigueras.

HL: The Milan Triennale this year is titled Unknown Unknowns. An Introduction to Mysteries, and seeks to raise a series of questions about what “we don’t know that we don’t know.” How do you understand your work in this context? Beyond the fact that dreams are an unknown space, how do your speculations contribute to think not only about the idea of the collective dream, but also about collective desire, about the common, the political, about what belongs to all of us?

HL: Your practice in general is related to the idea of tequio, our position in the world as social beings and the relationship between art and life. How do you approach these questions during this specific project?

HL: To close this conversation, can you tell us about your participation in the triennial? How has your process been and how has your work been received in this context?

DGN: In the triennial I received comments from the selection jury, where they expressed their interest in knowing more about other narratives linked to dreams, learning and midwifery. They also expressed the relevance of conceiving other ways of assuming our relationship with the botanical world, even with the one that comes from within us.

Comments

There are no coments available.