Extract - arte contemporáneo Decoloniality devenir instalación Lima planta de coca proyectoamil Sara Garzón Ximena Garrido-Lecca - Latinoamérica Mexico Peru

Sara Garzón, Ximena Garrido-Lecca

Reading time: 7 minutes

29.07.2022

EXTRACT is an online section where we share some of the texts published by Temblores Publicaciones, Terremoto’s publishing house. We present the tenth extract of this section, “Vegetal Becomings” by Sara Garzón, from Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum Coca. This publication is a retrospective review of the installation Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum Coca by Ximena Garrido-Lecca exhibited at proyectoamil, Lima, Peru, in 2019.

Vegetal Becomings

by Sara Garzón

Ximena Garrido-Lecca investigates Peru’s colonial legacies by revisiting the country’s history of extractivism and the consequent depletion of the national territory. In her previous works, the artist has underscored how national aspirations of progress have threatened the ability of local communities to sustain life on Earth. Recovering vernacular materials and methodologies employed in Peru’s rich craft, art, and architectural traditions, the artist’s experimental installations ultimately disclose how modern land management and mining have systematically destroyed ancient and local agricultural knowledges, advancing, in turn, what sociologist Rolando Vázquez has termed earthlessness.[1] Some of these works include the 2017 installation titled Botanical Insurgencies: Phaseolus lunatus featured at Sala de Arte Público Siqueiros in Mexico City, the installation Umbrales (2019), the series Destilaciones (2014-2016), and Aleaciones con memoria de forma (2014-2019). However, while the abrupt modification of the environment is at the center of Garrido-Lecca’s concerns, her project Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum Coca (2019) focuses instead on indigenous technologies and epistemologies, which are invoked by the spiritual and cultural practices associated with coca culture in the Andes. Presented in Lima at the independent space proyectoamil in 2019, the site-specific installation addressed the nature of coca plants not as resource or commodity but as agents capable of worlding the world.[2]

Harvested with the guidance and oversight of ENACO – Peru’s National Coca Company – and cultivated in an innovative, yet unsustainable, hydroponic system, the installation offers an ironic commentary on the industrialized process of coca growing.[3] For the duration of the four-month exhibition, proyectoamil served as a laboratory for the systematized cultivation of coca plants, their use in divination, and the subsequent categorization of people’s destinies into an organized archive or herbarium, which the artist called “a repository of contemporary preoccupations.”[4] Despite the scientific display and use of hydroponic planting, the very cultivation of coca as an art installation presupposed attention to the animist qualities of the Erythroxylum genus.

For the project, the artist organized over ninety plants in an industrial-looking setting to advance Andean concepts of knowledge, technology, and nature while simultaneously questioning scientific thinking as the only possible form of objective knowing. Without seeking any concrete resolution, the installation juxtaposed the mystical and the scientific, the industrial and the rural, the logical and the superstitious, the past and the future. The project, in that regard, had less to do with the politics of coca planting and its association with cocaine or drug dealing, and more with the massification of planting and agricultural modes that de-earth vegetal life and de-world communities’ millenarian relationship with it.

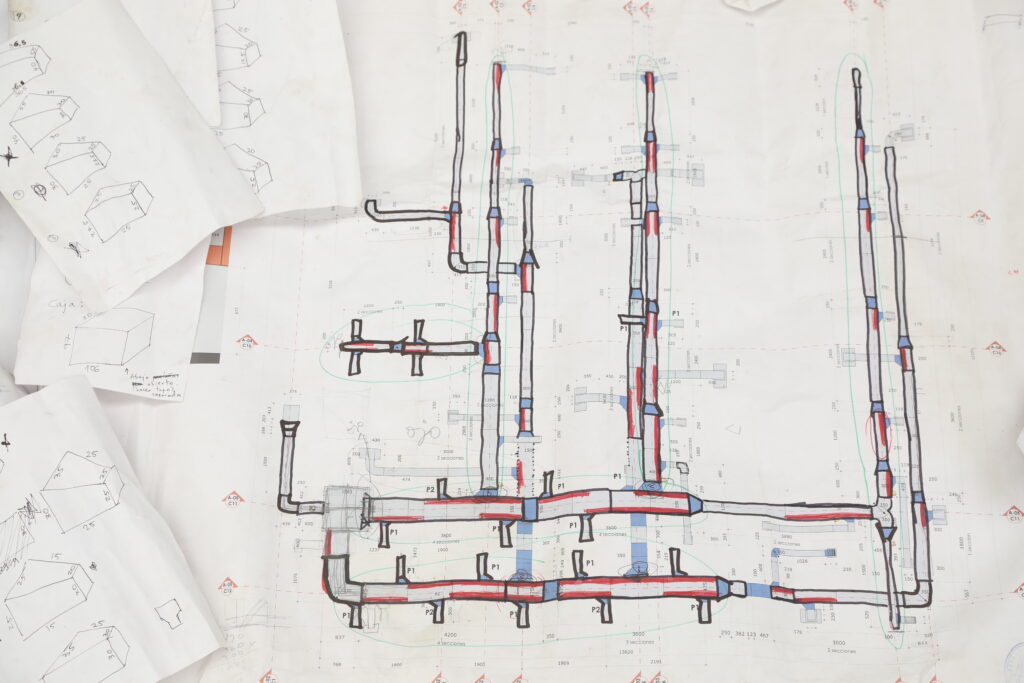

The industrial cultivation of coca presented by the exhibition, however, directly undermined the plant’s cultural significance within millenarian Andean communities. [5] In the gallery, the sterile white space was filled with intricately organized structural air ducts and aluminum water containers that supported the carefully harvested plants. The plant’s growth was then aided by powerful LED lamps that extended across the undulating hydroponic system providing light to the plants in this artificial environment. The sharp angles of this aluminum system echoed the overhead air vents that are characteristic of commercial buildings, poignantly underscoring the fact that coca plants are already subjected to highly engineered processes to permit their widespread consumption as part of cultural practices, but most notably as pharmaceutical products and in the cocaine industry.

The sophisticated and sterile installation added a particular dystopian note to the site’s inherent sense of postindustrial ruination. In fact, the site alone, a white cube gallery inside a semi-abandoned shopping mall, presupposed the vast and even illegal commodification of the sacred plant. Illegal not because it is against the law but because it reveals the corrupted use of plant knowledge that has historically profited from indigenous epistemologies for the advancement of science, and more specifically, Big Pharma. In that regard, the intricate scientific laboratory created an awkward tension. This tension stems from the incommensurable contradiction presented by the piece whereby the overtly technoscientific display and organization of information contrasted with the prophetic qualities of the plants, urban shamanist practices, and the mysticism of those visitors who trusted vegetal insight.

While at first glance the project conveyed a dystopian feeling with the misplaced industrial harvesting of coca inside a shopping mall, the installation should not be misinterpreted as a form of ecocriticism or even an expression of anthropogenic aesthetics. Rather, the installation recuperates a type of interspecies relationality that challenges nature’s definition as a mere resource. Unlike Garrido-Lecca’s previous works, Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum Coca can be best situated alongside what Canadian anthropologist Natasha Mayers calls the Planthroposcene, which is not a geological era but rather an epistemic framework with which to understand vegetal life.[6] According to Mayers, the Planthroposcene “invites us to stage new scenes and new ways to see and seed plant/people relations in the here and now.” In that sense, Garrido-Lecca’s work results in a new-materialist installation about animism and plant intelligence, asking the urgent question: How can we (re)connect to the millenarian Andean practice of listening, conversing, and learning from plants´ capacities to shape the world around us?

While the installation’s overbearing industrial infrastructure might seem to dominate the piece, the hydroponic structure only served the purpose of cultivating the leaves for their interpretation, which made the work participatory and semi-performatic. The divination sessions that were offered to visitors at no cost followed the custom of curanderismo, which originated in precolonial times. For Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum Coca, the prophetic reading was, however, not conducted by community healers or shamans but by a group of researchers from the Instituto de Cultura y Metafísica Oriental (Institute of Eastern Culture and Metaphysics, ICMO). In a departure from rural mystical practices, the urban researchers from ICMO consulted the coca leaves for answers about people’s most pressing concerns. Visitors were able to hear their individual readings in a small private room within the gallery that was decorated to evoke a divinatory setting that included ceramic vessels and an Andean ceremonial tapestry. The ancestral understanding of the plant as both a medium to help transform and heal as well as a portal to determine and even predict the destiny of human and nonhuman actants was then invoked to underscore coca´s multifaceted intelligence.

For the divination readings, the urban shamans of ICMO allowed each visitor three questions. To summon their answers, the coca leaves were thrown onto a piece of white paper. The leaves were thus endowed with the capacity to respond to a person’s preoccupations and were interpreted according to their color and arrangement when they fell. Through the mediation of a human interpreter, visitors came to the plants, spoke to them, and allowed themselves to enter into intersubjective relationships with the vegetal world. In addition to the reading, students at the National Agrarian University of La Molina (UNALM) stood by large white tables wearing laboratory coats to correctly categorize the leaf-covered papers produced by the readings in a well-organized herbarium. Standing inside the gallery’s glass doors, the students diligently logged the many questions and answers in a chart next to the leaves’ exact placement. Although the identity of the participants always remained anonymous, the “reason for consultation” was recorded and archived in a botanical cabinet that was kept throughout the exhibition and still exists as part of the artist’s personal collection. Beyond reading and responding to people’s preoccupations, the coca divination stood in contrast to the creation of an herbarium and its allusion to the Wunderkammer. The cabinet of curiosities, a foundational apparatus for Enlightenment thinking and Western Cartesianism, was hereby interrupted and problematized. The employment of taxonomies, categorization, organization, and administration of information in the installation clashed dramatically with the “mystical” power of the vegetal world to enable the future, a term that designated that which always remains unknowable. In that sense, when facing the herbarium in the exhibition, one cannot help but ask: How can a system designed to organize knowledge possibly organize the unknowable?

Find this full text in the printed version of Botanical Readings: Erythroxylum coca by Ximena Garrido-Lecca here.

According to Vázquez, “modernity’s anthropocentrism, built on the separation between the ‘human’ and ‘nature,’ requires the negation of earth. Modernity’s notion of humanity and civilization is produced as earthlessness. This negation is implemented through forms of classification, appropriation, extraction, consumption and pollution.” Earthlessness, moreover “as the loss of earth’s diversity signal[s] the irretrievable loss of the relations that hold alternative trajectories of hope, alternative relations to earth, to community, to language, to bodies, to ourselves; alternative forms of worlding the world with earth.” Rolando Vázquez, “Precedence, Earth and the Anthropocene: Decolonizing Design,” Design Philosophy Papers, vol. 15, no. 1, 2017, 2-9.

Ibid., 3. For additional references to worlding, see Helen Palmer and Vicky Hunter, “Worlding,” Newmaterialisms.eu, 2018. Available at: https://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/w/worlding.html (last accessed April 15, 2021).

Empresa Nacional de la Coca (ENACO) is a Peruvian state company dedicated to the commercialization of the coca leaf and its derivatives. It was created in 1949, but it was not until 1982 that it became a state company. For more on ENACO, see: www.enaco.com.pe/es (last accessed April 15, 2021).

Ximena Garrido-Lecca, interview with Sara Garzón. Phone conversation on April 16, 2021 [author’s translation].

With Andean I am referring to the diverse and heterogeneous community-based practices and belief systems shared across the Andean Mountain region in South America.

Natasha Mayers, “How to Grow Livable Worlds: Ten (Not-So-Easy) Steps for Life in the Anthropocene,” ABC Religion & Ethics, January 7, 2021. Available at: www.abc.net.au/religion/

natasha-myers-how-to-grow-liveable-worlds:-ten-not-so-easystep/

11906548 (last accessed April 15, 2021).

Comments

There are no coments available.