26.09.2016

Daniel Garza Usabiaga analyzes the ideological dimension of religious representation in the painting Cristo de la paz (1970) by David Alfaro Siqueiros

Muralist David Siqueiros’ Cristo de la paz (Peace Christ; 1969-70) is related to a new modern-era genre, promoted by a number of governments as well as institutional entities and given over to representations of political prisoners. Additionally—and within the context of the Cold War—this artwork relates to the rebels of its day: priests who radicalized the Church’s social doctrines, guerrillas, revolutionaries, prisoners of conscience and social activists. They are rebels who, while their hands are tied and though they await their demise with temperance, remain resolute and shall not surrender. This class of artworks was generally promoted in non-communist nations, as part of abstract solutions and in allusion to treatment of prisoners of conscience in the Soviet Union and other Warsaw Pact countries.

In Cristo de la paz, Siqueiros gives this logic a twist by means of an encrypted representation. Through the figure of Christ, the muralist articulates a realist image of the political prisoner and is thus able to emphasize his and her existence in other—putatively democratic—parts of the world, then under the sway of the United States. The relationship between Christ and the prisoner of conscience is not arbitrary. Siqueiros explicitly declared “it’s worth remembering Christ was a political prisoner, crucified more because of his revolutionary political ideas than for his religious notions.” In this painting, unlike in most modern, non-figurative religious art produced in Mexico, Siqueiros managed an articulation between Catholic iconography and highly political content. The success of such a maneuver comes from a strategy of encryption, a tactic deployed in art from the Cold War period in numerous parts of the world, that introduced a “hidden” message into an image that at first glance might seem innocuous.

Cristo de la paz was the sole Mexican artwork displayed when the Vatican Museum’s new contemporary art galleries opened in 1973. Its realism is of interest since it allows us to see the Catholic Church’s position on the ideological struggle between abstract and figurative art in the Cold War. Documents issued following the Second Vatican Council, an undertaking that concluded in 1965 during Paul VI’s papacy, made clear the Church lent no relevance to the dispute, making religious art a representational arena that transcended art-production-related ideological conflicts. Vatican II’s “Holy Liturgy Constitution” section entitled “Art and Sacred Objects” states “the Church never considered any particular artistic style as proper to it, but rather, adapting to different peoples’ character and conditions, as well as to various rites’ requirements, has accepted each epoch’s forms and created over the centuries an artistic treasury that merits careful conservation. Similarly, the art of our time and art of all peoples and regions must be freely exercised within the Church…”

This position stands in contrast to Pope Pius X’s 1910 encyclical entitled Sacrorum antistitum, which includes what has come to be known as the “anti-modernist oath.” It framed the Church’s position on a number of issues in the first half of the twentieth century, commenting on the impossibility of contemplating or understanding “the absolute and immutable truth as the apostles preached,” in accordance with context and historical circumstance, or, put more succinctly, “dogma cannot be altered to what each era’s culture may consider best or most appropriate.” Therefore, except in a handful of cases in certain places around the world, it can be said that Catholic art and architecture during the first half of the twentieth century were scarcely innovative and resisted actualization. It was during the 1950s and 60s that a global renovation and modernization of religious art and architecture took place. These changes emerged from a nascent modernizing impulse at the heart of the Catholic Church, that began to question Sacrorum antistitum’s “anti-modernist” position at every level, in response to the experience of the Second World War and the postwar era’s historical circumstances. In 1956, Pope Pius XII sought out a new approach to contemporary artists by inaugurating a “contemporary art section” within the Vatican Museum; several more such contemporary galleries were opened in 1973 and featured work by artists like de Chirico, André Derain, Otto Dix, Lucio Fontana, Francis Bacon and Siqueiros’s Cristo de la Paz.

In the 1950s, Siqueiros undertook an intense promotional campaign, international in scope, traveling to several Eastern European countries as well as to the Soviet Union. In 1956, he also traveled to Egypt and India, where he was received by those nations’ presidents, Gamal Abdel Nasser and Jawaharlal Nehru, lending the journey an eminently political character. The artist’s stance expanded with a 1960 visit to Cuba, just after the triumph of its socialist revolution. He met with Fidel Castro, who sat for several portraits at the end of the 1960s and in the early 1970s. The artist’s high profile, associated with communism and an emerging group of new, unaligned lay states, whose positions skewed to socialism, possibly ended up being a problematic “disturbance” in contrast to ever-more Pan-American foreign policy that characterized then Mexican president Adolfo López Mateos’s (center-right) PRI-party administration. Siqueiros’s actions were also interpreted as a slap in the face to the president himself, who could not stand that the artist’s reception in various quarters was not unlike that offered heads of state. When the muralist returned to Mexico after visits to Cuba and Venezuela on 9 August 1960, he was sent to remand prison and accused of “crimes of social sedition.” Following a trial in which the content of his artistic production was used against him, he was jailed at Mexico City’s notorious Lecumberri prison until 13 July 1964. It was the longest period of imprisonment he ever experienced, accompanied by an absolute, state-decreed local-media blackout on the matter.

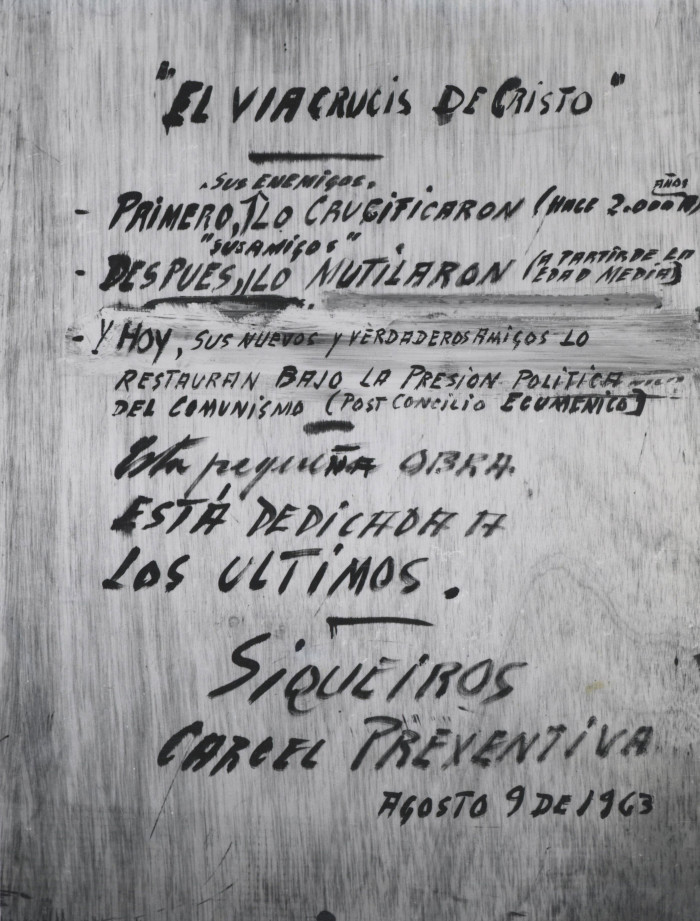

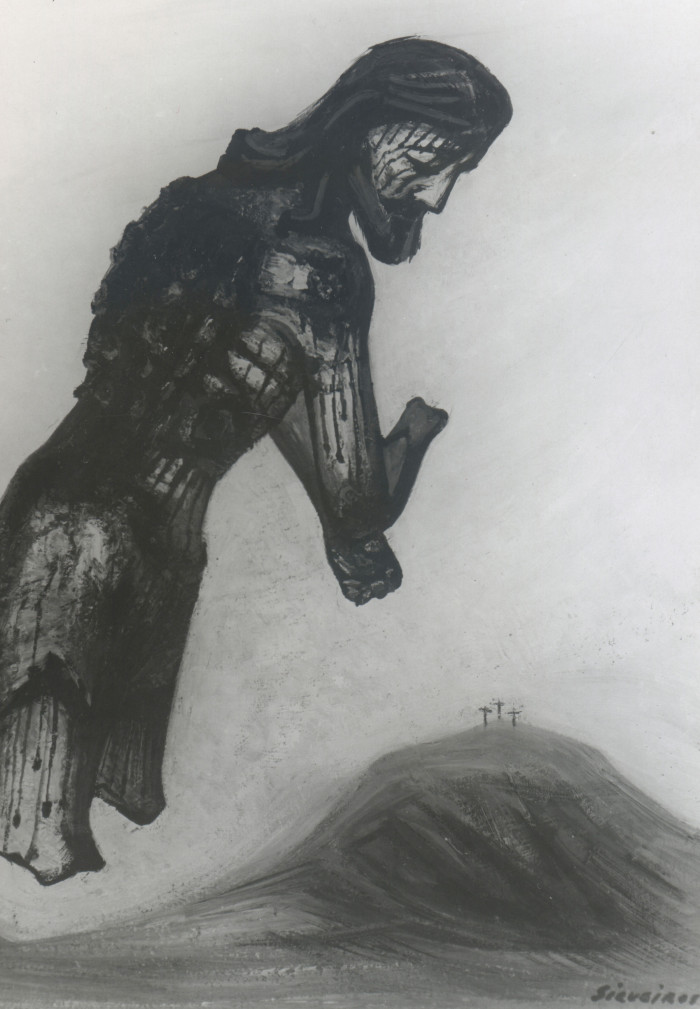

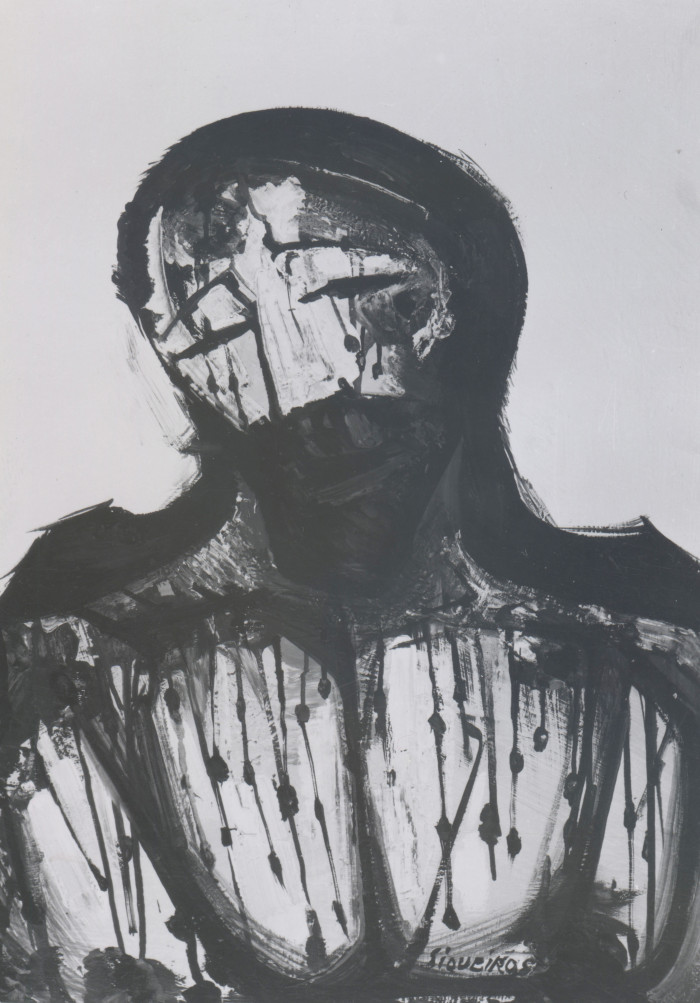

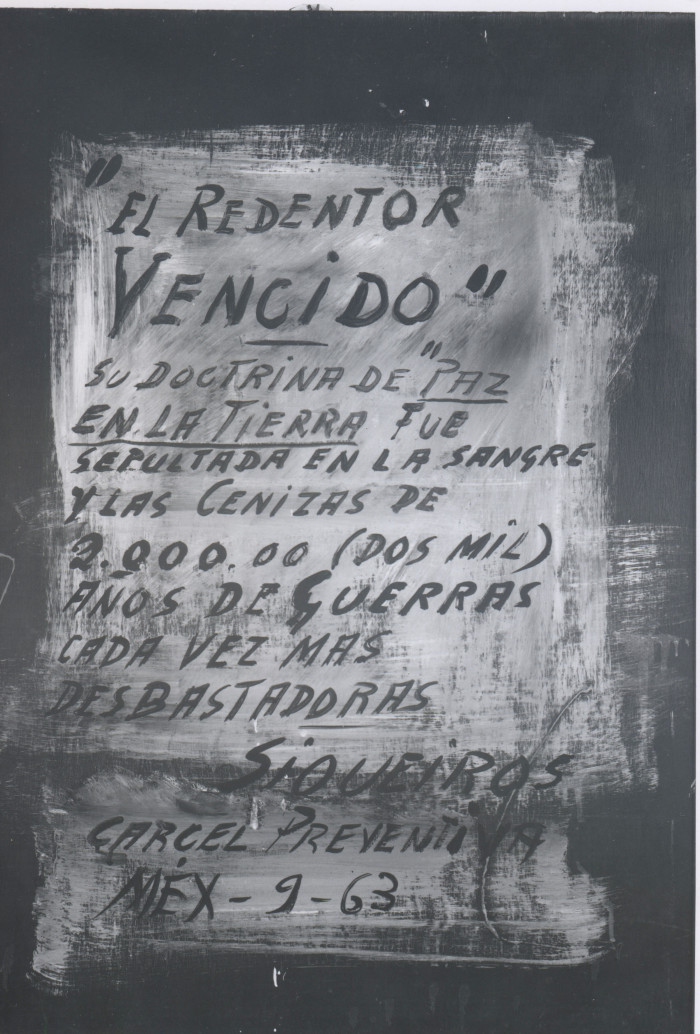

During his imprisonment, Siqueiros painted a series of Christ images including those known Cristo, Cristo mutilado and Cristo, redentor vencido.It is well known the artist grew up in a fervently Catholic atmosphere; the artist himself mentioned that his first encounters with art came through its religious iterations. The imagery in these paintings has a great deal to do with that background—or as much can be assumed—because of an inscription that accompanies one of the artworks. “‘May only he who believes in Christ paint Christ,’ wrote Fra Angelico. No doubt that’s why I’ve painted Him while remembering those terrible Christs I believed in as a boy.” Most of Siqueiros’s Christ images portray Him lacerated, viciously maimed and—as may have been the case with the wooden estofado-technique Christ that occupied part of Siqueiros’s jail cell—bleeding profusely. That recourse is what lends the paintings a certain expressionist nature that is underlined by a number of inscriptions the artist made on the back of the artworks. In the case of Cristo, el redentor vencido that inscription reads: “His doctrine of peace on Earth was entombed in the blood and ash of two thousand years of ever more devastating wars.”

In addition to biographical data, we can speculate Siqueiros painted these religious images because of a certain identification between Christ’s martyrdom and the artist’s own unjust imprisonment, a relationship that fits easily into the mythology the artist sought to articulate around himself. It may be more pertinent to point out that his interest in religious painting had to do with new Church social doctrine devised over the course of the Vatican II Council, whose most active and productive years coincided with the time Siqueiros spent in jail. Clearly the artist was well apprised of the advances being generated within the Vatican and it is also quite likely that he was aware of the emergence of certain social experiments throughout Latin America that sought to reconcile Catholicism and Marxism (as an extension of new social doctrine) in everything from new community model formation (as was the case in the Mexican states of Morelos and Coahuila) to its consequent social analysis and armed conflict, as happened in Colombia and in cases such as that of Father Camilo Torres Restrepo. Siqueiros’s empathy with regard to these changes in the Catholic Church is displayed in the inscription on Cristo mutilado, clearly his most “expressionist” Christ among those he painted at Lecumberri. The accompanying text, entitled “El Viacrucis de Cristo,” states: “First his enemies crucified Him (two thousand years ago). Then “His friends” mutilated him (starting in the Middle Ages). Today His new and true friends have restored Him under communist (post-Economic Council) political pressure.” For Siqueiros, an unstinting atheist, the strength and validity of communism’s political discourse had even had an influence on the Vatican, historically one of its biggest and fiercest detractors.

Four years following his release from Lecumberri Prison, Siqueiros was among artists invited to contribute artworks to an expansion of the Vatican Museum’s “contemporary art section,” a project Pope Paul VI kicked off at a 1964 meeting held with a large assembly of artists at the Sistine Chapel. Siqueiros completed Cristo de la Paz to that end, between 1969 and 1970, when he was living in Cuernavaca and working on the mural entitled La marcha de la humanidad. Throughout those years, says Mónica Montes, the woman charged with overseeing his holdings, Siqueiros had struck up a close relationship with Bishop Sergio Méndez Arceo. It’s likely his appreciation of the Catholic Church—and specifically of Pope Paul—had increased in the years following his release from prison. On a 1965 trip to New York (that also served as background to Roman Polanski’s film Rosemary’s Baby) the pontiff openly criticized US involvement in Vietnam. The pope went on to publish the progressive 1967 encyclical entitled Populorum progressio, on labor issues, that called for just wages, job security and medical care as part of any job, at the same time it defended workers’ right to form labor unions. What’s more, the document emphasized that peace is conditioned by social justice. Populorum progressio elicited fierce criticism and a palace revolt against Paul VI, within the Vatican, on the part of a faction led by Marcel Lefebvre; Lefebvre was among those who labeled the pontiff “the communist Pope.” Siqueiros’s sympathy with regard to the Catholic Church in these years may also have grown because of the emergence (if not emergency) of Liberation Theology that came out of the 1968 Medellín Conference of Latin American Bishops.

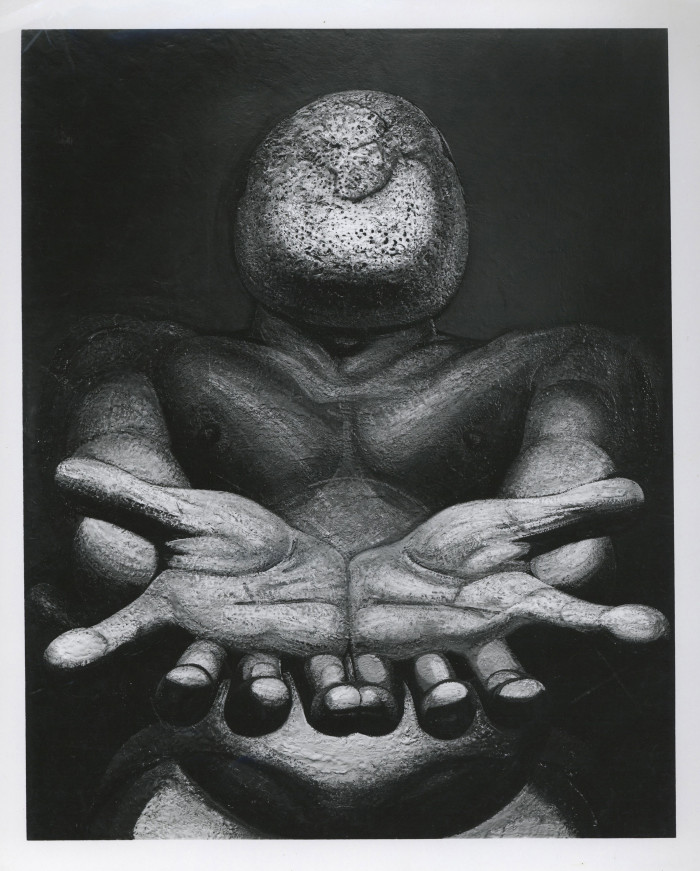

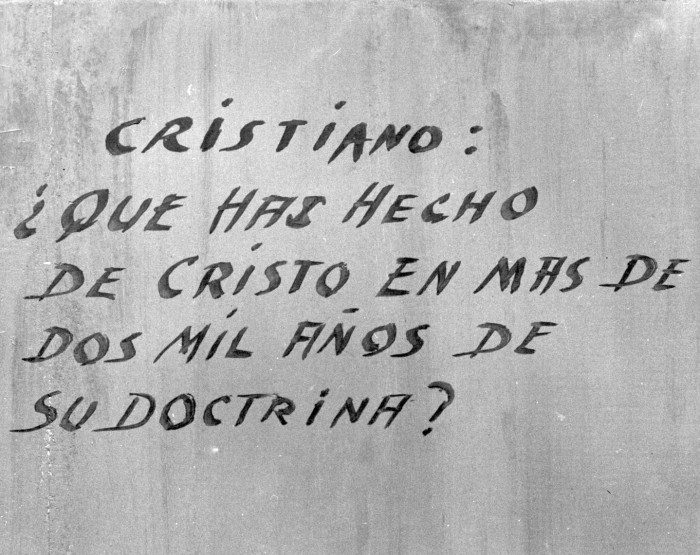

Cristo de la paz presents a radically different image than that of the religious paintings Siqueiros completed during his years of imprisonment. Here expressionist sensibility disappears and a type of representation that could be called “heroic”—that distinguishes a number of the muralist’s artworks—enters onto the scene. Raquel Tibol described the figure in the painting using adjectives like “imposing” and “majestic.” Though cut up and bleeding, Christ’s body is whole, is not gaunt and is possessed of a firmness comparable to the male body in the 1947 painting known as Nuestra imagen actual, an artwork with which Cristo de paz is easily related in formal terms. To complete the painting, the artist recurred (as in the 1947 piece) to a photographic, or “close-up” approach. The muralist himself served as the artwork’s model and in photographs he commissioned he appears with his arms extended forward, his hands clasped and fingers intertwined as if they formed one fist, an element the artist employs as a gesture of struggle and empowerment. Christ’s fetters therefore pass to a secondary plane; the dynamic strength of the clasped hands is the element that seizes the center of the painting. Cristo de la paz expands the pose by means of Christ’s face, in profile, which exhibits no signs of weakness. The painting shows the crown of thorns and includes a beard as elements characteristic to portrayals of Christ. On the back of the artwork he would deliver to the Vatican, Siqueiros wrote out a strongly worded query to men of faith: “Christian, in over two thousand years of your doctrine, what have you done with Christ?”

The artwork allows for a consideration of Siqueiros’s increasing appreciation of the figure of Christ, evidently seen from a secular point-of-view. As the artist wrote, “I admire Christ, but don’t get me wrong. I do not admire the religious Christ; I admire Christ as a political figure because I consider Him a rebel. Let’s be clear: Christ was the first great man to fight imperialism; He had the courage to confront powerful Roman oppressors yet with hardly any resources.”

An understanding that updated Christ’s image—something antithetical to the “anti-modernism oath”—was a commonplace in many initiatives clergy created throughout Latin America in an effort to reconcile Catholicism and Marxism in those days. It is enough to recall the best known and most radical such enunciation, from Colombian guerrilla priest Camilo Torres Restrepo: “Jesus would be a guerrilla if he were alive today.” The rebel as a postwar cultural construction took on a hip representational edge thanks to the culture industry of the era, principally Hollywood cinema, at the same time a number of figures from the social activism realm were seen as rebels in light of their questionings and struggles to undermine the status quo. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was clearly the most visible of these and his photographic portrayals, obviously, have been discussed more than once in relation to religious iconography. Besides being a rebel like Jesus, Che also became a martyr as a result of his 1967 assassination.

Once it had been displayed in the Vatican Museum’s new galleries, Cristo de la paz left no doubts about Pope Paul VI and the Second Vatican Council’s position with regard to art in the context of the Cold War. Religious art ignored any ideological struggle between figuration and abstraction and was able to include figures like Siqueiros: an avowed communist and atheist whose previous work included works with a fierce anticlerical nature and who considered Jesus “(the first) Bolshevik of His time.” After symbolically handing the painting over to Pope Paul VI via the pontiff’s Mexico representative, Monsignor Rafael Vázquez Corona, Siqueiros chose to grant the public access to the artwork, reproducing and including it as one of the exterior mural panels on the Mexico City structure known as the Polyforum Siqueiros, first opened in 1971. From the point-of-view of an “encrypted work,” Cristo de la paz’s exterior panel can be seen as an explicit political commentary of the historical context surrounding the Mexico of the time and essentially as a sort of denunciation—in the best muralist tradition—of the “dirty war” Presidents López Mateos, Gustavo Díaz Ordaz and Luis Echeverría had unleashed against hundreds of Mexican civilians. The mural Cristo de la paz not only attests to the artist’s growing admiration for the figure of Christ—as a symbol of rebellion against the societal status quo—but as well to the strategies to which the artist was obliged to recur as part of conditions surrounding artistic production at that time, to create artworks with strong critical commentary on the era’s political situation.

Comments

There are no coments available.