13.03.2017

São Paulo-based artist Ana Mazzei discusses with Terremoto’s editor in chief Dorothée Dupuis about politics of spectatorship in her work, public space in Brazil and how art’s independence vis-à-vis reality is actually what commits it the most strongly to the current affairs of the world.

Dorothée Dupuis: Could you tell me about Espetáculo (2016), the large scale work you presented at the last São Paulo biennial, Incerteza Viva?

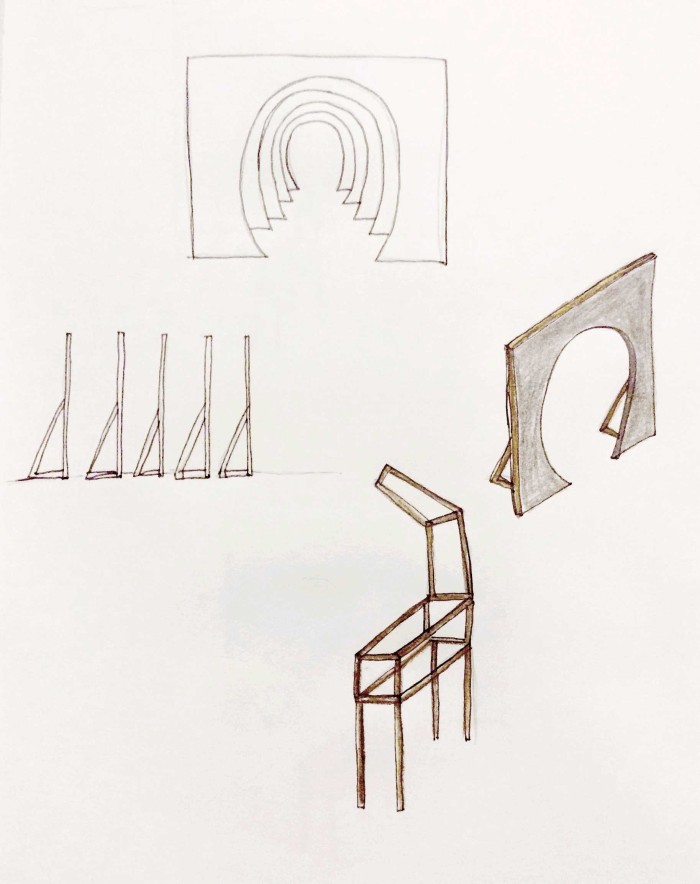

Ana Mazzei: It’s a project that started with a lot of sketches that I showed to the biennial curator Jochen Volz and his team when they first came visit my studio. I was concerned by size and dimension, and I wanted to make something big to stage a visual fight in front of the viewer. I was thinking about how objects made by hand affect the spectator’s understanding of the object’s materiality versus its abstract qualities. Also, I was drawing old instruments made for looking at things, like magnifying glasses, devices to look at the sun, and objects used to navigate specifically during colonial times. To have a spectacle, you need a spectator. At the beginning I wasn’t thinking directly about Guy Debord’s understanding of the “society of the spectacle,” but of spectacle as anything offered to the viewer. Spectacle becomes a universal category of what is seen. It’s a very simple concept, but it defines a lot of how I look at and make art.

DD: Did these relationships already existent in your previous smaller works?

AM: I have one work that is very important to me in this regard, Nova Knossos (2013). The piece attempts to establish a specific relationship to the spectator with its small dimension. I was looking to create a relationship where the spectator felt very big, as if she was growing like a giant, and could see cities as small objects. Another way to envision it is the small size of an airplane in the sky seen from the ground, when in fact it’s an enormous object. Things get bigger when you get closer: it’s a simple concept about the body and something that was present in that installation as much as in the Espetáculo installation. Also for this later work, I had to think differently about material and fabrication, because a lot of other people intervened in its making: the curator, the technician, and security. . . The scale created challenges to getting the work done, something that doesn’t happen with smaller works, where you have more control than with institutional projects but I like this instability.

DD: In Éxtase, Ascensão e Morte (2016), and Garabandal (2015), the works are some kind of prosthesis that reduces the distance between the spectator and the object to nothing, as they are in contact.

AM: The work is all about this! During my masters program I was studying Occidental art from the 15th century, early renaissance, when painting started to be canonized, i.e. framed, squared, and so on. For a long time the painter was tied to reality, but with the onset of photography, painting’s relationship with representation loosened up and the painter engaged with elements that fictionalized the idea of landscape. I was also researching the relationship of painters and viewers to the landscapes of colonized land and also portraiture, how photography changed that too. The works you mention are actually directly inspired by the tools that photographers used in the 19th century so their models didn’t lose a pose for the long exposure time that was needed.

DD: A lot of the objects you create are inspired by actual objects?

AM: Yes, the existing objects and poses I draw from, belong to stories and possess a cultural meaning —a memory, although I don’t like this word.

DD: Why?

AM: I think memory is a very personal thing. Also it has this anecdotal, psychological connotation. I prefer to talk of relationships, and analogies.

DD: These people in the pictures, do they stand in as any spectator, or are they performers?

AM: They could be anyone. At first I was thinking about a very strict way to activate the works, but finally I decided to let them go free and let people use them as they want.

DD: Would you connect this thread with historic Brazilian works, like Parangolé by Helio Oiticica (1964-65), that give the viewer an option to physically engage with the work, or alter its form?

AM: I remember as a child going to a São Paulo biennial and touching an object from Lygia Clark. So to me, these processes are part of us, of Brazilian art history! I like to touch things. We live in a moment when it is good to break through this barrier, the idea of frontier is very important now —it started with colonialism of course— but now it is even more important to be able to touch an object, to go through this barrier. I have other projects connected to touching that propose different interactions with the viewer: things you can wear but that aren’t outfits, or things that cover your face.

DD: Can you talk about this unrealized project of yours with the horse and the tunnel? It intrigues me so much.

AM: [Laughs] It’s an installation with a wooden horse and a kind of tunnel made by walls with holes. The horse will pass through this tunnel. I would like these walls painted in different color scales, and the horse made of wood. I’m not thinking of a proportional horse, like a chair horse, it wouldn’t look like a real one. You can relate to the horse, to the walls. I thought about putting some wheels on the horse so the viewer can move it into the tunnel, move it around, like we do with horses. It’s only an idea for now.

DD: Could you tell me more about the use of color in your work?

AM: When you look at an object, the image of this object is the result of the stimulation of the visual organ by light energy. My interest in color is directly associated with the understanding of how color is constituted in the human eye and in the construction of a visual field.

DD: Among these unrealized projects, I also like the video of the two men discussing, entitled Is collage art? We talked about it a while ago, but I haven’t seen it.

AM: It’s because I haven’t finished this video, but I really would like to… Two guys talk about music and at some point, they take a cardboard coffin into the room. It’s kind of a surrealist story. It brings me to the idea of directing, since the video has this comedic tone. It’s all about how not to be too serious. It feels good to laugh. Both of these works that we are talking about, this one and the horse, have a connection with reality but the connection breaks with the entrance of the coffin, or the fact you can move the horse around. I like to create a space for momentous craziness.

DD: Could you attempt to define your video work by itself and maybe in relation to your sculptural work? Do you intend to try to associate these two sides of your practice in the future?

AM: I think of video similarly to how I think of theater, as a way to formalize a scene watched live. Close-ups and actions in the background come to mind. In theater, this is a multi-faceted relationship, there is the exchange between the elements that constitute the scene. In a very simple way, it makes the spectator more conscious of the whole process (things happen before his eyes), but the construction of a film requires those visual elements to be fragments within the cinematic montage… It’s a game between the screen and the scene, and this magnifies the power of the montage when it’s used to articulate the actor on stage, with his double projected on the screen. It is a confrontation between space and time. This is where the scenario and the props are present: the concept of theatricality implies a notion of spectacularization, in which aspects of everyday life are re-signified in the manner of a spectacle, establishing a new relationship with the world. This procedure is possible through the act of constructing a fictional reality.

DD: We have been talking a lot about abstraction, so I want to talk about the use of text in your work, especially the videos: I especially think of Bartira e João Ramalho I (2014), Com um gesto de impaciencia (2014), and Ode ao bode (2013).

AM: This is related to breaking the conception of a pre-existing space for art. In my videos, when I use dance, performance and documentary images, I look for texts that I take from a specific environment to recreate in my own reality. For example, when reading Greek theater, which I like a lot, I make a connection to my own moment by changing the context of the text. I make it fluid, accepting that some cultural elements cannot be embraced nor interpreted other than just looking at the text with your own view, or from the view of the spectator. In If they say I was a bird (2015), I mix some texts by Aristophanes, a Greek writer, with ones by Oswaldo de Andrade, a Brazilian 20th century author connected to the Anthropophagy movement. They are not connected, but in my way of thinking they are. The collage builds a fictional world based on history but that is happening right now. It connects the realities we are living in.

DD: What is this theater group you mention in your bio, Teatro Facada?

AM: Teatro Facada is an experimental project of collective creation based on theatrical games and exercises. I invite people, not many —about 3 to 5— to read a text that may or may not have a theatrical origin, together. Simultaneously with the textual reading, we are proposing manners and versions associated with the intensities of the text. Actually here comes the use of color. Reflecting on the emotional meaning of the text, the name of the color arises by interpretation. In most of the events, only the audio is recorded and I then make drawings based on the encounter. This technique also works to imagine and represent spaces or architectures.

DD: You made various sculptures installed in public space or at least conceived for it. I always think that outdoor art has a specific dimension in Brazil where I feel the public space has been damaged during the dictatorship, when, on the other hand, there is carnival and all this street culture and so on. Can you talk about these works?

AM: Here in Brazil we have the combination of a supposedly tropical environment, with the unreal use of the public space. There are aesthetic and ideological relationships associated with Tropicália and the political debates that took place in the 60s and 70s. However, it is in the tension generated by the dialogues between the aesthetic and ideological that one can glimpse the best gains for the history of contemporary art. I think the Brazilian public space was never properly used as a space for art. It may have association with the dictatorship, but the experiences of that period paradoxically seem to me more successful than many of today. Also, when I think of public installations or sculptures, I am thinking of the relation between the work and the viewer’s participation. The way people can deal with this relationship to the work creates a change of perspective, that might allow resistance to the concept of the work as a finished product, and keep the work connected with the idea of experience.

DD: In general, how do you feel a practice like yours can connect to a complicated political moment, at the scale of the country and the part of the world you live in? You were talking earlier about the historical contexts that informed the history of painting in the west, for example. I like to think that art has a direct connection to representation, to our perception of reality. Do you have any comment on that?

AM: How I can comment on these sad things happening in the world, like the refugees crisis, Trump’s election, the coup in Brazil and so on? Well, I am thinking of art as a space of experience, it’s the only way I can discuss this. What I feel is that when we do art we are necessarily thinking about the moment in which we are living, and of course, art needs to talk about it, but I don’t think art needs to use the terms that are connected to the real world. Art has to be a place to think about possibilities and experience, not to use political terms as a trampoline. Do you see what I mean? I feel art needs to be a mysterious place, where you don’t know exactly what is going on, not completely exposed, or directly connected to any one thing. About Brazil —and maybe it’s a blatant or too simplistic example— but if I think of what happened to the president, well I don’t need to use her real name. . . I am thinking about how things can be discussed by not using the terms of the newspapers. Artists can be talking about what’s happening without being masters of specific subjects or medium: political art, performance art, or video art. They might rather say, let’s just try to experience these different things and in a couple of years we will be able to talk about them with a bit more distance.

Comments

There are no coments available.