20.03.2017

Florencia Portocarrero highlights the historical importance of Peruvian artist Elena Tejada-Herrera’s practice and its relevance to understand the experience of migrants in the current political panorama.

I

Except for scant inclusions in collective exhibitions and a handful of mentions in specialty publications, Elena Tejada-Herrera’s work has been left out of recent years’ accounts of contemporary Peruvian art. The omission has not only to do with the fact the artist has lived outside Peru for fifteen years, but primarily because of her insistence on elaborating a syncretic visual language that, by questioning gender relations and other identity categories, allows her to question public life and intervene in the re-creation of collective sensibilities. To that end, the artist had to initiate an alternative model for the circulation of her work, that —based on “guerrilla” style interventions in urban and virtual public space— revealed the blind spots of the circuit Lima’s art establishment legitimates. An anti-formalist and undisciplined impulse that traverses her work has made her an artist hard to classify and, despite her centrality to contemporary Peruvian art history, easy to marginalize.

Elena Tejada-Herrera began her artistic education in the mid-1990s, specializing in painting at the Arts Department at Pontificia Universidad del Perú, an art school that promoted the development of a subjective and “a-politicized” language. However, the artist soon lost her interest in “pure forms,” and began to assert a vocation for what we might call a promiscuity regarding the use of media. Indeed, on a formal level, Tejada-Herrera’s artistic practice is situated at the intersection between performance, installation, video and “socially engaged practice.” This intense hybridity of form is not merely linked to her commitment to feminism, and to exploring sexuality and female erotic desire, but constitutes a critical stance to the art market fetish logic as well.

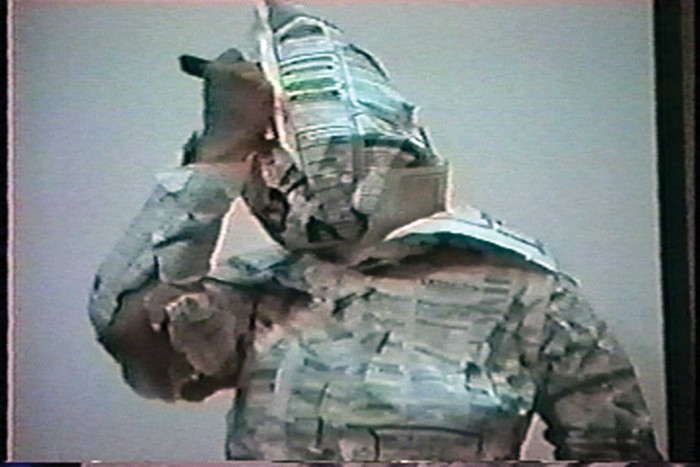

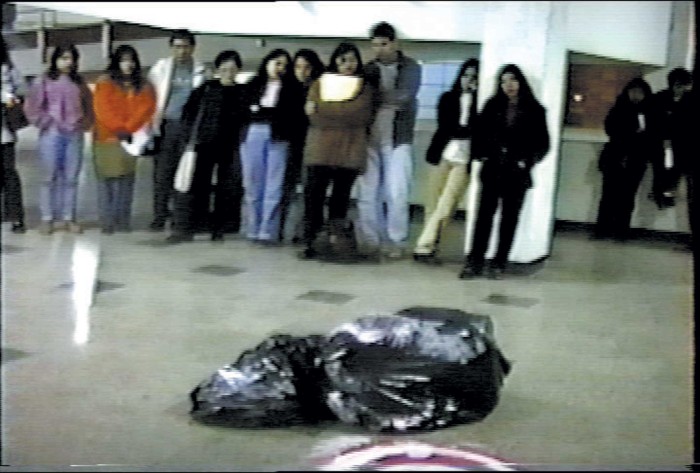

Despite the fact that Tejada-Herrera’s contribution to the devel- opment of contemporary Peruvian art is increasingly recognized, her reputation rests almost exclusively on three performances she realized and documented in the second half of the 1990s, during the “Fujimontesinista” dictatorship. [1] The first is Señorita de buena presencia buscando empleo (1997), in which she burst into a round-table discussion at the First Lima Ibero-American Biennial [2], in an outfit made of clippings from a newspaper’s help-wanted section. The costume only exposed her crotch, calling attention to the Peruvian labor market’s reigning racial and sexual authoritarianism. Recuerdo (1998), was an action in which —emulating a corpse sealed in a black plastic bag— the artist dragged herself across the courtyard at the Universidad Nacional de San Marcos literature department as she cried out the names of students a paramilitary commando had murdered in 1992, in an act of state terrorism known as the “La Cantuta case.” And finally, there was Bomba y la bataclana en la danza del vientre (1999), in which Tejada-Herrera performed a shoddy exotic dance next to cross-dressed comedian. The piece was a clear indication of her interest in rubbing high against popular culture by recuperating a politically incorrect sense of humor from the street.

I would like to argue here that these first three Tejada-Herrera performances constituted a space of political revelation in two senses: As a woman-citizen, to the degree they presented a feminine corporality that —aware of its class- and race-based privileges— demanded public deliberation in a society where parity within the debate is not within every citizen’s realm of possibilities. And as a woman-artist, by confronting the locally predominant patriarchal modernist canon through a questioning of traditional artistic disciplines and notions such as “the work’s quality” and “good taste.” Along similar lines to what theorist Amelia Jones [3] posits in relation to certain US “body art” practices, we could say Tejada-Herrera’s performances activated a mode of “dramatically intersubjective” [4] artistic production for the first time in Peru. Establishing a convulsive relationship with her audience, the artist made visible how identities are articulated dialectically, each forming the other, through a continuous exchange of desires and identifications.

The artist’s constant attempts to articulate her personal story in its social context and to postulate these themes as defining issues within the public-sphere intersubjective dynamic, may well have constituted her most original contribution to Peruvian contemporary art. Nevertheless, her quest to democratize her language and audience found a critical vacuum. It was precisely due to a lack of referents and interlocutors that in 2001 the artist traveled to the United States to undertake an MFA as a fellow at Virginia Commonwealth University. [5] Since the artist left Peru, relatively little has been written about her more recent work, leaving a void that only now is being filled by renewed interest in it. [6] What I seek to do here is make up for that lack of information by focusing on a very specific, not-yet-studied moment from her artistic trajectory: her earliest productions in the United States, through an analysis of three specific performances: Accents of Color (2004-2006), One Day Around the neighborhood Choreographing Me (2006) and Nouveau Bourgeois Latin American Immigrant Who learned shopping and Has Good Taste (2004-2006).

II

The MFA that Tejada-Herrera completed between 2001-2003 at Virginia Commonwealth University promoted study practice in painting, drawing and engraving. It was a program in which the interdisciplinary was not encouraged, so once again the artist found herself hobbled in attempts to develop projects that went beyond those disciplines. Nevertheless, the broader university context did allow her to explore other topics and visual languages. It was within this framework that she first had access to digital editing, the use of color and filters.

This period of experimental freedom came to an end when Tejada-Herrera finished her studies and decided to stay in the United States to apply for citizenship. To that end, she moved to Williamsburg, Virginia —a small city that can be seen as a living museum of the US colonial identity—and took on jobs in nearby cities that allowed her to fulfill requirements for permanent residence. Her change in status from “foreign student” to “immigrant” had immediate, important repercussions both in the way she lived and in her artistic production. Unlike in Lima —a hybrid, mixed-race city where Tejada-Herrera enjoyed of a privileged space of enunciation [7]— in Williamsburg she was subject to a minority position, doubly marginalized within the social hierarchy: that of being a woman as well as a Latin American immigrant.

Between 2003 and 2006, Tejada-Herrera had no studio in which to produce and store her work. Moreover, the milieu of which she had once formed a part at the university started to disappear, ultimately leaving her immersed in an alien social dynamic. In this precarious, solitary context, her performance practice became the only means to continue creating and, thus, a reaffirmation of her identity as an artist. Lacking means and resources, yet once again following a “guerrilla,” “do-it-yourself” logic of taking to the streets that had characterized her Lima interventions, the artist decided to live her work rather than just exhibit it.

When Tejada-Herrera takes stock of this period, she insists these performances also allowed her to both apprehend and integrate herself into her new context. Thus despite the original bewilderment she felt at a lack of city institutions dedicated to contemporary art, she soon realized that in many US working-class communities, “the market” is not only the place where salaries are spent, but is also a space of encounters, sociability and cultural exchange. With an irreverent take on these social dynamics, Tejada-Herrera’s performances acted as a quirky reading and interpretation-machine for her circumstances. This quasi-hermeneutic use of performance —based on a decoding of mass symbols— allowed the artist to find a place as a cultural producer, despite her condition as a minority/immigrant subject.

Accents of Color (2004-2006) encapsulates the living situation described above quite well. With the realization that in the United States, clothing is bought much more cheaply than supplies for painting, Tejada-Herrera decided to acquire clothes in highly vivid shades and would then go into the streets while imagining she was painting with her body. While the documentation of this action shows the artist as a “spot” of color in wide-open, at times abandoned spaces (highways, parks, shopping centers) in Williamsburg, it also documents her first incursions into other, more populous and cosmopolitan urban centers. In Williamsburg, the artist seems lost in herself, standing in the same locations for several hours. That said, in more populous areas, interaction with the public turns Accents of Color into a participatory piece. For Tejada-Herrera, this action implied transforming the performance into an extension of her in-studio visual practice. Yet it can also be read as an attempt at “visibility” within a social framework that tends to disappear subjects that, like her, do not embody a prototypical form of citizenship.

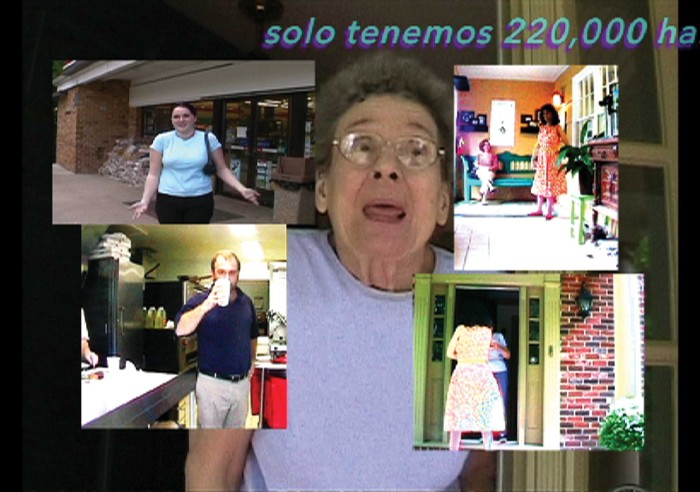

One Day Around he Neighborhood Choreographing Me (2006) is a multi-channel, highly colorful video filled with superimposed images and sounds that document a performance Tejada-Herrera made in her Williamsburg neighborhood in 2006. At first the voice of the artist is heard off-camera, in English with a heavy Latino accent, comparing life in Lima and the US. The artist goes door-to-door until she manages to work her way into her neighbors’ houses. The proposed exchange features a naïve tone that appeals to or reinforces fantasies of the Other, in this case an ingenuous, infantilized immigrant. The initial conversation revolves around clothes and other consumer habits. When a certain amount of trust has been built up, the artist asks her neighbors to teach her a dance. Surprisingly, the dances make evident that even in Williamsburg, citizens’ origins are quite diverse.

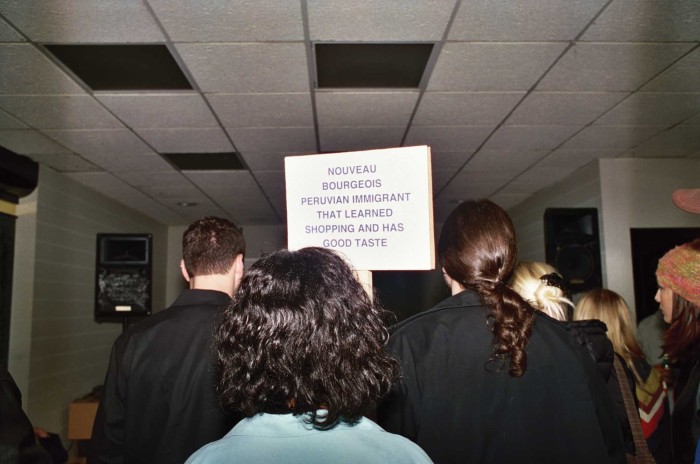

Finally, Nouveau Bourgeois Latin American Immigrant Who Learned Shopping and Has Good Taste (2004-2006) is an action the artist performed for a number of years in various cities in the states of Virginia and New York. The performance’s documentation begins with a four-channel projection. Elena Tejada-Herrera appears, standing and evincing an affirmative gesture at the entrance to a Williamsburg shopping center, brandishing a small sign that reads “Nouveau Bourgeois Latin American Immigrant Who Learns Shopping and Has Good Taste.” The artist is dressed in garments that call up clichéd, vintage femininity: pearls, colorful skirts or dresses and high-heeled shoes. Her apparel’s codification as stereotypically bourgeois contrasts with the evidently more popular origins of passers-by, who constitute an audience for the effects of this action. Immediately thereafter, the artist appears “in character” at different cultural institutions in the college town of Norfolk, also in Virginia, performing interventions at concerts, art galleries and cocktail bars. Finally the video takes us to New York’s Union Square. On camera and in front of passers-by, Tejada-Herrera changes outfits several times, as if experimenting with the various identities she can take on through clothing. In general, the video has an ironic tone and presents the artist as self-conscious, reclaiming bourgeois origins, spending power and good taste, all the characteristics that do not correspond to the typical image of the Latino immigrant in the US public sphere.

III

Elena Tejada-Herrera has never thought of herself as a “producer of objects.” On the contrary, she has sought to anchor her work to its context and to have the work dialogue with that context. Therefore —beyond formal elements that move through the performances described— what interests me is to think of how they function at once as an index and a subversion of immigrant subjects’ experiences in the United States.

In his book Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, [8] Cuban-American academic José Esteban Muñoz maintains that affirming a sense of the self that includes political agency is an arduous task for subjects in whom more than one minority position in the social hierarchy converge. These subjects find themselves obliged to negotiate identity in dialogue with a generally adverse, or even phobic, majoritarian public sphere that makes them invisible or even punishes them for not embodying an ideal citizenship. Or, put another way, for not conforming to the logics of hetero-normativity, white supremacy and misogyny that underlie the formation of the US nation state.

Elena Tejada-Herrera’s performances return to the public eye a subjectivity that normally does not have a voice with which to produce its own interpretation of the world, and has been simultaneously subjected to a dual process of racialization and racism. With humor and an irreverent attitude, the artist generates short-circuits within processes of identification, problematizing grotesque representations of immigrants in the US public sphere.

On more than one occasion, Tejada-Herrera has referred to a sense of humor as one of her most important professional tools for minimizing tensions and allowing “the Other” to be identified, or draw near to her life experiences without reacting defensively or aggressively. But humor doesn’t only exercise a communicative function in her work. As Freud stated in on humor, [9] appeals to a humorous attitude —as opposed to other intellectual activity processes— speak of a self that refuses to recognize the affronts reality affords it and insists that trauma from the outside world can not only not touch it, but is in fact a source of pleasure. Therefore, while the artist’s performances testify to a desire for integration into the new social context that takes her in, use of parody also speaks of a relationship of insubordination in light of as much. This, therefore, is a self that fights to de-identify itself from the toxic, stereotypical image of the Latino immigrant and reconstruct its identity from a more amenable or even seductive place.

José Esteban Muñoz defines de-identification as a survival strategy minority subjects employ to resist socially prescribed models of identification that generally constitute damaged stereotypes. Thanks to different versions of Tejada-Herrera’s immigrant self —whether these be poetic, subtle, infantilized or affirmative— the phobic object is reconfigured and repaired. Seen from this perspective, we can affirm that humor in the artist’s work functions as both a political and pedagogic project.

In Trump’s “America,” where celebration of the patriarchy, misogyny, xenophobia and racism are rapidly replacing the liberal common sense that developed thanks to the historic struggles for civil rights, representations that seek to activate new meanings of the self and new social connections are more urgent than ever. The political efficacy of performances of a self in opposition to definitive and grotesque categories lies in that they are capable of forming and empowering a counter-public. These representations make it possible for the spectator —often other minority subjects that have been rendered invisible— to imagine a world where it is indeed possible for their life experiences to be taken into account in all their complexity, and to resist the assaults of a new political environment based on fascism and intolerance of difference.

Notes

[1] The “Fujimontesinista dictatorship” is how the period between 1990 and 2001 has been named. During these years former president Alberto Fujimori and his advisor Vladimiro Montesinos set up a mode of governance equal parts strong-man, populist, crony-ist and just plain abuse of power.

[2] The discussion into which Tejada-Herrera intervened was one of the most eagerly anticipated at the biennial because its invited speakers included figures of international renown such as the Cuban curator and director of the Havana Biennial, Llilian Llanés; Mexican curator Raquel Tibol; Brazilian critic and curator Paulo Herkenhoff and Paraguayan curator Ticio Escobar, et al.

[3] See Amelia Jones, Body Art: Performing the Subject, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Personal communication with the artist (April 2016).

[6] At Proyecto AMIL I recently curated Elena Tejada- Herrera, Videos de esta mujer: registros de performance 1997- 2010. The exhibition gathered twenty-one performance documentations the artist created over the course of almost a decade of artistic production in Peru and the United States.

[7] Due to a series of identity-related characteristics —i.e., being white, drawn from the educated, bourgeois classes and an artist— Tejada-Herrera occupied a privileged position in her native Lima.

[8] José Esteban Muñoz, Desidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics, Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

[9] Sigmund Freud, “El Humor” in Obras Completas de Sigmund Freud, Madrid: Amorrortu Editores, 1998.

Comments

There are no coments available.