28.07.2018

By Lee Escobedo, New Orleans, Louisiana, USA

March 22, 2018 – July 22, 2018

As US American men were funneled into the European theatre during WWII to breathe their last breathes, the sounds of drums rolled through the homes and factories back home. It was a calling by a country for its women to fill roles once excluded to them by society. Churning at a brutally slow pace for progress, post-war US America finally gave quarter, granting women the flexibility to finally pursue working roles within many spheres, including the arts. As societal shifts often do, pushes for equality and changebroke in waves during the 50’s. The art world was discovering abstraction, influenced by the European surrealists who migrated to the US during pre-war instability. This new artistic form provided the framework for female artists to explore creative freedom. To enter the halls of the Ogden Museum of Art in New Orleans to witness The Drum Will Sound: Women in Southern Abstraction, is temporary escapism from the sound and fury of US America’s social and moral destabilization. It’s also a reminder of how little ground we’ve made socially since that last great war. Gender imbalance within the arts still fails us all, as men still mostly dictate what’s shown and supported.

The Drum Will Sound brings together artists from the last 80 years under the show’s umbrella of “Southern abstraction”, showing the scope of women’s influence on the movement since the 40’s. The works chosen for the show come from the muscle of the museum’s permanent collection, featuring Margaret Evangeline, Cynthia Brants, Halocyne Barnes, Ruth Atkinson Holmes, Betsy Stewart, Millie Wohl, ValerieJaudon, Vincencia Blount, Shawne Major, Clyde Connell, Sherri Owens, Anastasia Pelias, Jacqueline Humphries, Lin Emery, Minnie Evans, Ashley Teamer, MaPo Kinnord, Marie Hull, Dusti Bongé, Bess Dawson, and Ida Kohlmeyer. Each artist created work through the lens of various decades, reflecting the cultural shifts and discoveries of their respective times. The exhibition traces these shifts within abstraction and lets the ladies take the lead.

The Southern region of the U.S. has been a hotbed of the “isms” that have wrecked this country for centuries. US American Evangelicals have made the South into a voting block for the support of Conservative values, pushing a moral-based platform that marginalizes women, minorities, and the LGBT community. Loosely tying together all these Southern-born female voices, under unifying banners of Abstraction, gender, and region, works as loud, brash resistance.

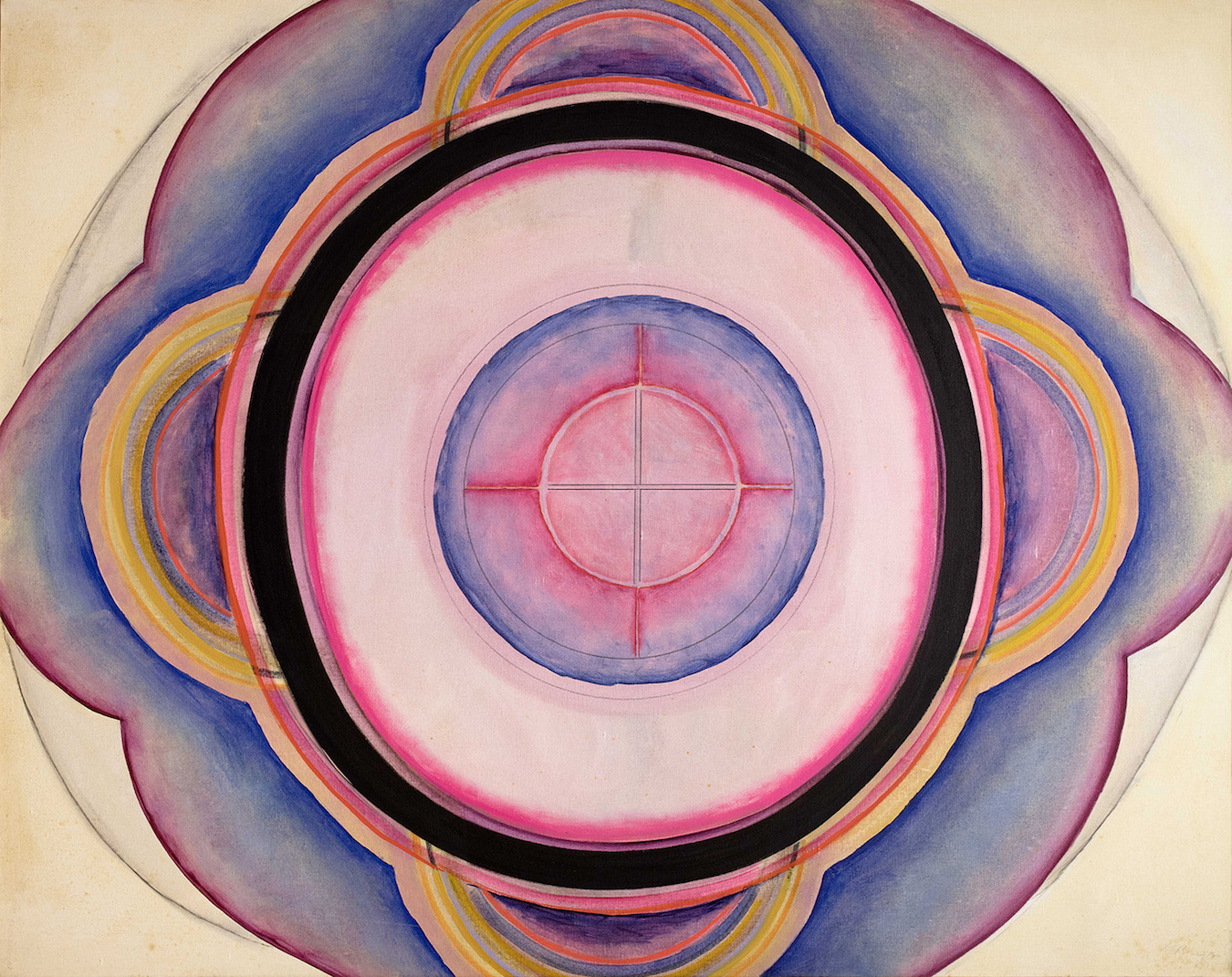

Although selecting works only from a museum’s permanent collection could lead to limitations, the Ogden has clearly been on the right side of history for decades, amassing a brilliant collection of female artists. There is no need to look beyond the selected artists to understand cautionary tales of equality gone wrong: many of the artists, as many of their contemporaries, battled obscurity, neglect, and sexism throughout their careers. Curator, Bradley Sumrall refers to studying the permanent collection over the last 11 years and finding choice narratives woven through the many abstract works made by womensuch as the way the region has influenced experimentation, playing with Southern symbolism, and the way tough social climate influenced women to rise against challenges for progress.This lends itself to one of the main reasons this exhibition works so well overall. It ignores the easy route of political rhetoric in favor of letting the show speak for itself. Yes, all artists selected are women, but that’s not the only theme at play. The loose unity allows for a consideration of Abstraction’sfluidity in the way it can be interpreted and conveyed. You can find it in the psychedelic 3D zen of Kohlmeyer Rondo #2 (1968), whose soft Rothko inspired hues conceal an insanity inducing infiniteness. Each geometric line draws you into a slightly off-centered crosshair, potentially revealing the viewer to be standing, metaphorically, on not so solid ground. We meet Kohlmeyer again with Signs and Symbols 85-1 (1984), with depicts a map of semiology one might find cruising down the highway. Warped, chunky copies of houses, signs, and structures, are charted together in random accordance.

For minorities, the South can be challengingfor success and progress. But as history has shown us, within difficult climates, new ways of thinking, making, and being can arise. The female artists who survived the rigidity found along the South of the United States have been brought together as a testament of endurance. The myths behind Rothko, De Kooning, and Pollock were tied to the overstated male id that drove their free-form brushstrokes. Kohlmeyer and other female artists were working in linear progression with these male icons, developing new techniques and styles.

A standout, Dorothy Hood’s Florence in the Morning (1976) utilizes soft greens and pinks to stain the surface, creating a dream-like horizon line. Floating off-right are two of her totems, icons the artist played around with in various pieces throughout the years. Here the blue forms perform as sidewinding chateus from which to enjoy an Italian sunrise. Or yet, neutral obelisks exist within and outside of the paintings narrative, simply observing. Hood, who has been rediscovered recently herself since her death in 2000, is the rare painter whose work remains idiosyncratic as it is identifiable.

Thankfully, the show is not limited to strictly to painting, it also includes sculptural pieces by Connell, Kinnord, and most notably, Benglis. Over the course of her career, Benglis has been known to integrate ideas of protest into her work,such as her infamous 1974 ArtForum spread where she included a nude image of herself for an upcoming show at Paula Cooper Gallery. For this show at Ogden, bronze, nickel, and chrome are used to maximum the discursive power of the artist. For her piece, Minerva (1986) named after the Greek goddess of war, mimicking the floral shapes and regional iconography of her home state of Louisiana, sharp, pointed sheets of metal are fastened into petal like forms with a knotted middle. Benglis’ silver tumor rejects both decoration and the cold, impotent structures made by male Minimalists. The ugliness is laid bare, reflecting the glamourous-less bayou of her hometown before migrating to NYC.

The relationships between these women, sometimes spanning generations, are key to unlock the heart of the show. Benglis was tutored while at Tulane by Kohlmeyer, who was sisters with Whol; Blount, a native to Atlanta, was a contemporary of Kohlmeyer, while Owens was influenced heavily by Connell. And at the center of this genealogy is Bongé, who has been regulated as a footnote in the male-driven history of Abstract Expressionism. Her work, Circles Penetrated (1952) warps geometric figures upward through circles resembling vortexes. It features bold, angular forms built on a densely textured surface. The title itself can be seen as a cheeky nod towards the phallic symbolism of her male counterparts.

Knowing many artists in this exhibition were mentors and students, contemporaries and competitors, points to shared experiences between female artists rebelling against the status quo. If there’s one commonality between the artists threaded throughout the exhibition, it’s revolt. At the time of Abstract Expressionism conception, women were allowed to stake their artistic claim. The Drum Will Soundreveals powerful benchmarks in their progress.

Comments

There are no coments available.