19.05.2022

In her second delivery for Projector, Florencia Mamani explores the specters of an anti-racist audiovisual production that frees the challenges and boundaries of representation and fetishization.

Until the lions have their own historians, the history of the hunt will always glorify the hunter.

—African proverb

While I studied Film Directing at the Universidad de Cine – FUC, one of the analyzes that caught my attention the most was that of Nazi material. How do you go about taking those logs with that particular point of view and telling the other story? That is, the story of the ones that lost or the oppressed.

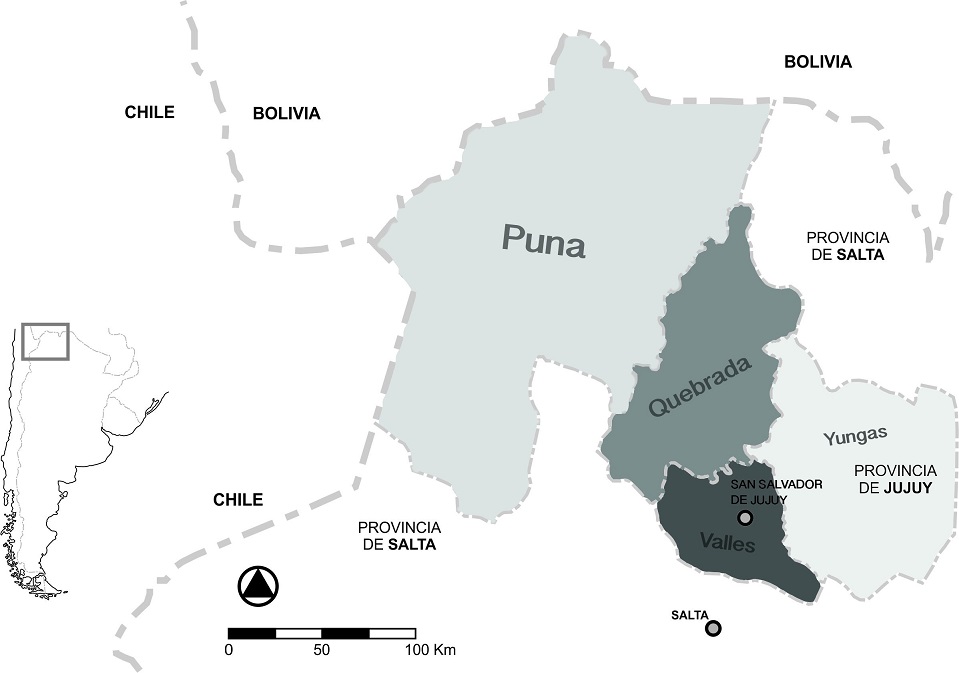

A few weeks ago I was at the Argentina border. I was received by a person with very good energy who introduced me to her mother. A very wise lady in several ways. I arrived with very strong mixed feelings. Angry but with that peace that I sometimes feel when I’m in the Puna in Jujuy, the place where my mother was born. Every time I’m there I look at the hills and those skies full of stars while the cold freezes my ears. I imagine how hard it must be to be a girl who has to go early in that cold to herd sheep and make sure they don’t get lost so as not to suffer maternal physical violence.

When I remember my mom I remember her watching TV (in addition to working). The attached video is a couple of years old. Me, Florencia Mamani, have spent a couple of years rethinking archival material regarding indigenous people or their descendants. It’s been a long time since I wrote something that I hope at sometime became a beautiful book that talks about an anti-racist audiovisual perspective in which other racialized indigenous people can find themselves. Today when I observe this first approach that I had regarding reflecting on my roots, I am a little ashamed how sometimes we do not fully understand each other with my mother, or how I was able to express myself about her.

For a lower-class racialized woman to be behind the camera rethinking her representation, and not only as an object of fetishization by opportunistic production companies, it is very difficult to move forward. It is very difficult for them to see that we can tell stories, that we can produce them, but that it will take more time. That is why while I was on the border looking towards Villazón, which is the Bolivian city that borders Argentina, I remembered representations that I saw that were carried out throughout Argentine history and those of today. In my case, I still haven’t been able to make an economic leap that would allow me to take many of my ideas further, and these unfortunately fall on those who were lucky enough to hear some of my ideas in private and reproduce them. Remembering this. I felt poor. I felt robbed. That weekend that I went to La Quiaca I did not cross the border. But I thought I’d come back as soon as I could to do it. It is necessary not only to generate more registrations but also to think about how to show ourselves.

The Soviet editor Esfir Shub, being in the editing section with Goskino, she re edited (censored) nearly 200 foreign films between 1922 and 1925 in order to bring them into line with Soviet political correctness. It must be taken into account that previously the USSR film industry did not have so many films to generate a strong Soviet cinema. But the point is that these shortcomings generated by the blockade of other countries against the USSR or its own government would generate the need for other solutions. And this would become a different set-up. Every cloud has a silver lining. The audiovisual construction / reconstruction of racialized indigenous people, or their descendants, is going to demand the best of us (of whom we are part of the audiovisual area). The formation of a documentary film movement with an anti-racist perspective will require the rethinking of those amateurs cinematographers, students and professionals descended from these “audiovisual exiles”. Even the new material in which racialized people appear, whether on streaming platforms such as Netflix, Amazon or public television channels, could be re edited and understand that we have not yet left that limbo of representation.

How to speak for ourselves? How not to repeat once again the fetishization of our bodies? How to show ourselves in front of the camera in a non-stereotyped way? Can I make my community, ancestry legitimize my artistic expressions? Will we depend and go back to the white colonizer pocket to tell who we are? The reconstruction of a “me as a collective” in the forgotten racialized indigenous people is a little more complex and naturally the material to be generated cannot completely escape from hegemonic values, resulting from the colonization depending on the american country we live in. Besides, many of these people do not know their indigenous roots, their indigenous ancestry. In the Argentine case, why are we still continuing being a voice of Jorge Prelorán, why still today? Today that we have our own technical resources and that we are more.

How to celebrate our racialized image as empowered if the ways of showing ourselves are exactly the same as the colonizing gaze? What about our identity?

Within this audiovisual counter-hegemony with many failed attempts, I trust, maybe even naive or utopian, that a new way of rethinking the audiovisual will arrive, or not new, but in accordance with other worldviews still existing on this continent. The number of tools has increased so much that it is possible to talk about new names or new audiovisual essayists of indigenous descent with a strong imprint and who go beyond the machinery of generating meaningless content for the simple fact of wearing an indigenous face. To bet on new narratives. The audiovisual essay at the head.

And so, perhaps, not to let them trivialize our image again.

Leave that nostalgia to which the image of the indigenous is subjected and a neo-fetishization disguised as institutional apologies.

Up to here we come. I’ll walk along the border with this damaged memory.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ycyZJEMafFA

Comments

There are no coments available.