18.09.2023

We invite the researcher, videographer and activist Pablo Gaytán to share with us his reflection on gentrification and its implications with whitening by dispossession, cultural industries and the modification of the sensitive based on interdependence with social networks. The first part of the commissioned essay.

Displaced urbanites1

Metapolis

An invincible stridency roams the city. The ceaseless mobilization of millions of urbanites is happening in the metapolis2, whether it be for work, education, construction, renovations, or for occupying its multiple public spaces, making it come alive or survive in the middle of a gigantic rhapsody of noise, rumors and sounds that have silenced the demands of an urban proletariat trapped in the digital network. A city that isn’t limited by the administrative state borders of Mexico City, extending into the neighboring states of Queretaro, Puebla, Morelos, Hidalgo and Estado de Mexico; each one with its own network of circulation, production and consumption infrastructures that result in the immense urban body integrated by all of these territories, in order to carry out different functions. The metapolis forms an inseparable and organic heterogeneous body that goes beyond the limits imposed by the state legislations.

There is no urban island; there is a metapolitan city that functions like a large combination of natural, mechanical and immaterial resource structures, which also include the computing networks that send information to the neural networks of humans and telecommunications. The city is a grand global cognitive golem that doesn’t stop; it even intensifies like it happened during the Covid-19 lockdown, or in the face of a military siege.

The city is not like any other self-creating machine. It functions, operates, produces and values capital thanks to the work, imagination, creation and wishes of its inhabitants: the urbanites. Every day, they mobilize, work, get themselves ready, donate their time, but mostly consume, so that the great capitalist machine survives. Yes, the metapolitan machine is capitalist, given that its urban infrastructure, foundations, and natural resources are privatized, whether they are originally community, state, institutional or cultural property. I’m referring mainly to the urban ground, that great raw material that is exploited and appropriated through the methods of eviction, displacement, dispossession (3D, for its initials in Spanish), and the speculation of the real estate market.

Nowadays, even if there is a rhetoric that proclaims the “communalization” of the lands and natural resources, the reality demonstrates that property isn’t social. Proof of it is the way in which rural, communal or reserve territories are liberated for the benefit of the real state agencies and transnational companies. Let’s all remember the paradigmatic case of Santa Fe, which became a 21st Century City in the 80s, where the original owners were stripped of their lands so they could be given away to companies like IBM, Televisa, and many others. This city government policy has continued up to this day, as promoted by the current Mexico City government through the General Land Use Planning Program (PGOT, for its initials in Spanish), which made the regulatory framework for rural lands disappear.

This way, the inhabitants, the citizens or the users –as the rulers and owners of urban territories tend to call the proletariat– are the ones that, through their work and strength –be it physical or cognitive–, make the machine work so it can produce the benefits accumulated by men with economical power.

Socially produced riches are appropriated by the metapolitan class (media entrepreneurs, creative industrialists, art speculators, owners of the entertainment and real estate industries), and the state nomenclature is protected by the offices of the bureaucratic apparatus. The real state capital and the State configure what I call the Real Property State; and yes, even today, these two entities have become partners to “stimulate the development” of the city as alluded to by the local government authorities.

The accumulation by those who have power occurs thanks to the physical, intellectual, mental and emotional exploitation of the urban proletariat. Another figure that now participates in this accumulation is the owners of the hypermedia platforms that, almost autonomously, control the minds of the prole-urbanites. They are the ones who watch over, see and hear the desires of the urbanites, and satisfy them momentaneously through the fetishization of the words and images that are obediently embodied in the citizens and in the social bases of the platform-State. A State reduced to digital offices for proceedings and collection, whose purpose is to direct progressive developmentalism. Thus, the members of the sub-metropolitan proletariat end up erasing their class identity, since they stop thinking of themselves as part of the proletariat or as bureaucrats at the service of the welfare state, and start thinking of themselves as consumers and future wealthy entrepreneurs. They learn to internalize the values of their capitalist master and state orders.

Sub-metropolitans

Seduced by the screens of the grand transmediatic digital golem, the urban proletarians lose sight of the fact that they are workers, and they start to conceive themselves as full-on consumers, without thinking how the obtainment of products isn’t in any way homogeneous, and remaining unaware of the unjust classist pyramid on which these forms of communism are built in the central metropolitan society.

Yes, the urbanite comes from the outskirts or the sub-city: the original communities in process of disappearing, the popular neighborhoods, social housing units, milpas occupied by tenements and migrants, and neo-traditional neighborhoods built in the last half century. They move from their living areas (dormitory housing, housing on credit, housing-workshop, housing of no more than 52 square meters, or housing-businesses) to their places of formal or informal employment, either on a motorbike paid in installments, squished inside a polluting minibus, in an illegal taxi , or in the inefficient public transport that will take them to the border nodes or Modal Transfer Centers (CETRAM, for its initials in Spanish). These transfer centers are pompously called that by the city government so they can hide the classism embedded in mobility options. They are urban nodes that signal in thousands of ways to a soft and “democratic” social apartheid. The members of the sub-metropolitan proletariat will have to transfer when they get off their deteriorated means of transportation and get into the innovative means of mobility. With a digital boarding card, they will be able to get into the Metrobus, the RTP or the subway grid.

In the massive distribution of the proletariat, the social peripheral homogeneity of this class diversifies, given that their stratification will depend on the border node through which they transit or move to their salaried, precarious, disqualified, multi-functional and hybrid work. Servers of servers, domestic workers or workers in the pornographic-cultural industry, workers at the service of the State, those who work in call centers, Uber or Rappi, educators and loaders, packers, seamstresses (-ters), or delivery people for the digital platforms, among many unimaginable new services.

The category of sub-metropolitan urbanites is integrated by a proletariat of servers of servers, through which many generations of indigenous migrants or inhabitants of original communities –who, due to dispossession or pollution of their lands, join these ranks– have passed. Also adding to this category, are the young professionals with a college degree that has no value in the metropolitan job market. The new trend is to be a self-advocate for your housing and its surroundings through the means of international platforms like Airbnb, as advertised with huge fanfare by the government of Mexico City3.For this kind of work, you will be a collaborative and serving proletarian. A “job” that is reduced to being a tourist guide while you operate a trajinera, or explaining the myths and origins of the “pueblos mágicos”. You could also work as a chef, a cook, a messenger, a loader or a merchant of handicrafts freshly arrived from China. There are also the assistants of the Airbnb “hosts”, like drivers, circus performers, sellout musicians, storytellers, and even makeshift translators and interpreters.

Menial work that reproduces the social relations of capitalist exploitation plundered through the consumption of junk food acquired in supermarkets or through digital platforms, the consumption of paid and “free” shows by artists that were once young, and which now ceaselessly promote the nostalgia of the unlived life. In the metapolis, the sub-metropolitan proletariat is a slave to consumption, and it consumes itself by consuming so it can get the most out of its meager income in the illegal flea markets, the markets on wheels, or in the recycling flea markets. They are reproducers of market relations at the neighborhood level, where the romanticized local economy is already almost non-existent.

From the neighborhoods, the capital is reproduced seamlessly and it produces media-cultural phenomena of cultural whitewashing4, as we can clearly see in the phenomenon of the neighborhood influencers in Tepito, where dozens of young people sell tours that show the originality of the neighborhood, the offers of counterfeit products, the procurement of college degrees, all of this through their posts and tik toks5. Consumption of low-quality merchandise stock –baled clothes– that produces extraordinary profits for (il)legal capital, making use of commercial waste and burrs to squeeze every last cent out of all types of products. The degraded consumption of the urban proletariat is a guarantee of the amplified reproduction of capital, even though it is accompanied by ideology. It is an alternative music and audiovisual industry that places at its center a kind of neo-savage popular culture of stasis with rhythms and messages of violence. In the end, this evidences the conflict between equals and stimulates the depoliticization of a proletariat involved in its own narcissistic gloating, or in a kind of “depressive hedonism”, that is, “an inability to do anything other than pursue pleasure6“, as understood by the British philosopher Mark Fisher

A large sector of this sub-metropolitan proletariat does not own housing, they must rent or occupy it. Over several generations, entire families have rented apartments, tenement rooms and rooftops in the central neighborhoods of the City, in the boroughs of Cuauhtémoc, Miguel Hidalgo, Benito Juárez, Coyoacán and Álvaro Obregón, where a rich neighborhood culture and economy had taken root. However, in the last three decades, they have been evicted, displaced and dispossessed of their rented or owned homes, towards sub-metropolitan areas, particularly in Estado de México, and the other states that make up the central metapolis. They have been subjected to different processes of whitewashing through dispossession –either economic, social, cultural or housing–, which has mobilized some social molecules of self-organization for the resistance and persistence manifested in the tenant, neighborhood, and citizen organizations that have proposed laws for the defense of tenants in the eviction process7, or imaginative forms of collective housing. Let us remember the movement against the Chapultepec Cultural and Commercial Corridor, which was finally rejected through citizen consultation in December 20158, thanks to the work carried out by a group of neighborhood groups and collectives.

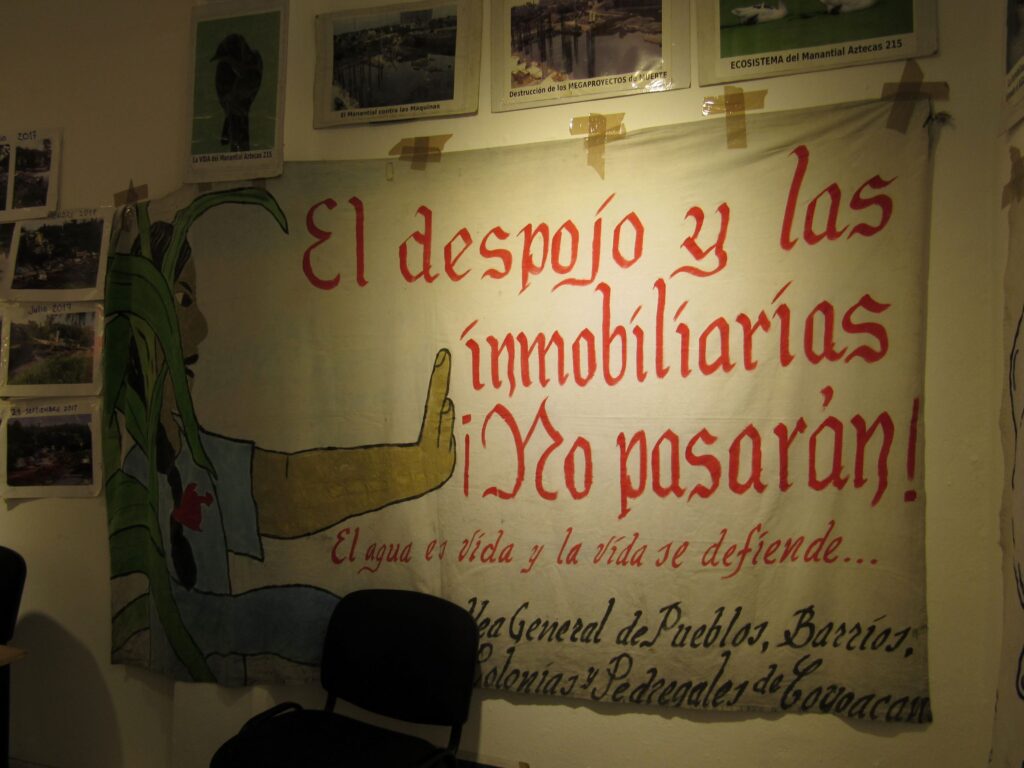

There are the movements in defense of water in the towns, neighborhoods and quarters of Coyoacán, as well as the defense of the wetlands in Cuemanco, and the status of communal land ownership in San Gregorio Atlapulco, Xochimilco, to name a few. These processes of whitewashing by dispossession in the metapolis have been conflictive and have led to massive resistance with a display of efforts, occupations, media initiatives, theoretical analysis and legislative proposals. In these endeavors, the so-called subaltern classes or sub-metropolitan and metropolitan proletariat have demonstrated great collective intelligence to contain the pernicious effects of the aforementioned urban-capitalist processes in the central metapolis. It is worth mentioning that these phenomena were previously noted two decades ago in my book Apartheid social en la ciudad de la esperanza cero9.

[…]

[1] The following essay contains some concepts and ideas that we have been developing in the Escuela Común Itinerante (ECI), a space for reflection around the resistance and persistence processes created by a group of organized urbanites which include Asamblea Comunitaria Miravalle, Fundación Barrio Unido, Casa de la Cultura Jarillas, Colectivo de Mejoramiento Barrial Comunitario [COMEBA], Unión Vicente Guerrero, A.C. [GAM y Ecatepec] [06600] Plataforma Vecinal y Observatorio de la Colonia Juárez. The writer of this essay is responsible for its content.

[2] Francois Asher, Métapolis ou I´avenir des villes (París: Éditions Odile Jacob, 1995). The sociologist studies the effects of mobility and new spaces and the urban lifestyles that welcome them. He values the meta condition as the natural evolution of a intense stage of civilization.

[3] Read my article La ciudad “turistificada” and “Airbnb periférico” Available in:

https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=586100106736713&set=a.528388282507896. Culturas Metropolitanas +40

[4] Pablo Gaytán, “Blanqueamiento por despojo: una categoría polisemántica descolonizadora”, in Ciudad en disputa. Política urbana, movilización ciudadana y nuevas desigualdades urbanas, coordinated by Javier De la Torre Galindo y Blanca Ramírez Velázquez (Ciudad de México: UAM, 2020), 262-269. I propose that there are eight forms of whitewashing. Among these are: “Cultural whitewashing whose processes tend to eliminate, decaffeinate or pasteurize local, neighborhood, traditional and community cultures through commercial projects that turn these territories into theme parks…” (p. 268).

[5] https://www.instagram.com/reel/Ct-Tf8LvNgs/?fbclid=IwAR1lklTKIHhi82rIbKsimhKOQma8eRQfLbEPpG3GoeY_WiMS3GCoozkkhrE.

[6] Mark Fisher, Realismo capitalista. ¿No hay alternativa? (Buenos Aires: Caja Negra, 2016). Read in particular the chapter of “Todo lo sólido se disuelve en las relaciones públicas: el estalinismo de mercado y la antiproducción burocrática”, p. 71-78.

[7] Article 60 of the constitutional law of human rights in Mexico City: https://obras.expansion.mx/inmobiliario/2019/06/12/el-articulo-sobre-desalojos-en-la-cdmx-se-modifico-pero-aun-hay-polemica.

[8] The citizen consultation was carried out on December 5, 2015. See more: https://www.iecm.mx/participacionciudadana/consultas-ciudadanas-en-la-ciudad-de-mexico/consulta-del-corredor-cultural-chapultepec-zona-rosa-2015

[9] Pablo Gaytán, Apartheid social en la ciudad de la esperanza cero. (Ediciones InterNeta: Distrito Federal, 2004). Available at: https://issuu.com/culturasmetaprolitanas/docs/apartheid.

Comments

There are no coments available.