12.02.2021

EXTRACT is an online section where we share some of the texts published by Temblores Publicaciones, Terremoto’s publishing house. Today we present our fourth extract, “The Final Years,” by Dafne Cruz Porchini, from José Clemente Orozco: Final Cut, a catalog of the exhibition of the same name—held at the Arizona State University Art Museum (ASUAM) in Phoenix, USA. As an accompaniment to the show, this publication revises the artist’s late production and displays a selection of unseen materials from his personal archive, while at the same time puts into dialogue the influence of the painter in contemporary artistic practices in Guadalajara.

José Clemente Orozco: The Final Years (1945-1949)

Between September 1945 and May 1946, José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) made his last journey to New York. In the final months of his time there, he was joined by his wife Margarita and daughter Lucrecia. In his correspondence from the time, Orozco, in addition to describing various aspects of his daily life in the metropolis he knew so well, allows us to glimpse facets of his creative process. Reflecting on his artistic production and professional growth in general, Orozco wrote to his wife in December of 1945: “Anyway, my stay here has been very useful these past three months, from a practical point of view. I have seen many things, met many peoples [sic] and [have] seen clearly what needs to be done for the future. I have seen that my prestige is more solid now than ever and that I have as many friends as I want.”1 It was at this same time that, thanks to Orozco’s own efforts, the renowned Knoedler Gallery began to commercialize his easel painting.

During this period, the painter felt an enormous need to transform his pictorial work, seeking to “renew himself, […] see other things,” and reconfigure his position in Mexico as well as in the United States. Commenting to his friend art historian Justino Fernández Orozco stated: “I will defend myself with my paintings.”2 In an interview with the journalist Richard Posner that appeared in the daily Free World, Orozco spoke of his artistic interests with a focus on technical, formal, and personal exploration. Posner announced: “[…] one of the principal reasons he came to New York three months ago was to find out what was happening in the world. Here, there is some of everything.”3 The painter was particularly interested in Harlem, a neighborhood he visited regularly. By the same token, the artist visited several museums in the city and took the opportunity to observe the artistic changes that were occurring as a result of the political climate and uncertainty of the Second World War. In brief, over the course of this journey, Orozco profoundly reworked his production, his role as an artist, and his environment.4

Despite already being a fairly well-known artist in Mexico’s neighboring nation, the painter did not want to be recognized solely for his mural work and aspired to intensify and make better known his labor in other formats: “The public still believes that I am only a mural painter, and Inés and her pintorcillos5 have contributed to this idea, in bad faith, and to their benefit.”6 Orozco was convinced of the contribution Mexican mural painting had made to American art but wanted to extend this idea: “many North Americans prefer Mexican painting: we have contributed in large part to what they aspire to do.”7 The idea of an “American art” was becoming increasingly linked to a hemispheric cultural diplomacy that saw visual arts as an object of exchange, building on the success and popularity of postrevolutionary Mexican art in the United States and its important influence on the public art projects of the New Deal.8

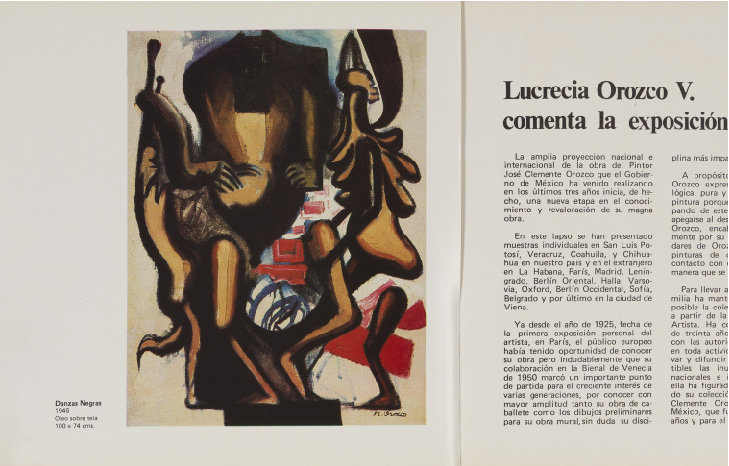

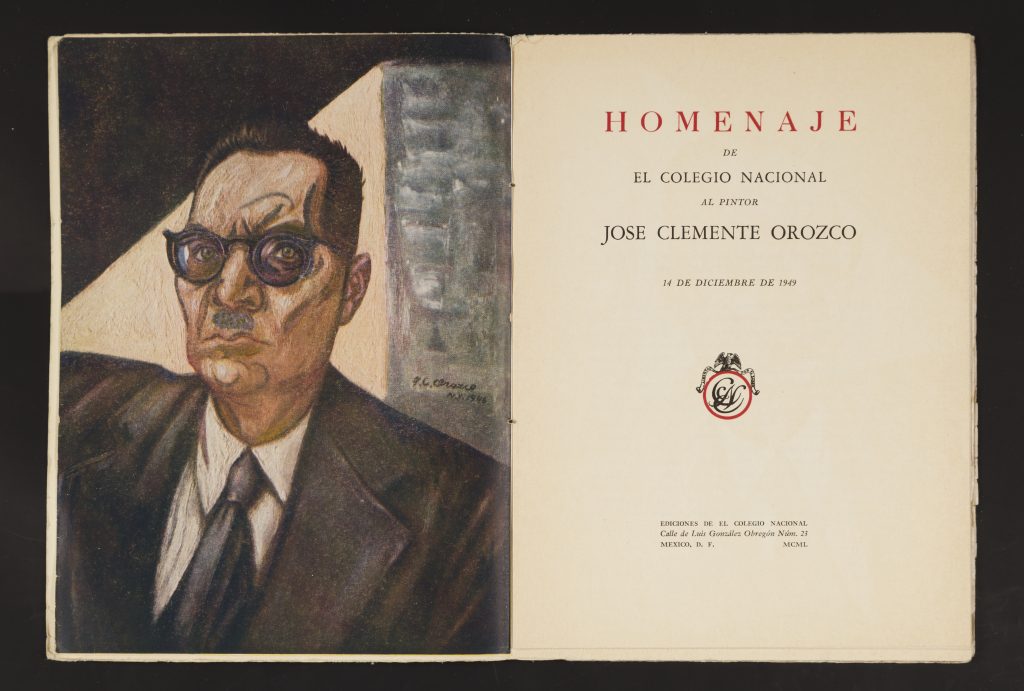

Indeed, the painter had received José Gómez Sicre on several occasions at his studio located on Central Park. The Cuban curator and art critic undoubtedly hoped to strengthen Orozco’s presence in the Latin American artistic circuits of the epoch and appeared to be pleasantly surprised by the turn in the painter’s work: “He is determined to take his art in a new direction, free of all reestablished connections and in favor of the unfamiliar.”9 However, Gómez Sicre also emphasized the international reach and reception of Orozco’s work, which had allowed the painter to position himself inside the category of American artists: “[…] He has filled walls and walls, so many thousands of square meters that they credit him with being one of the most fertile and accurate artistic workers America has produced to date.” And indeed, it was during that fruitful visit to New York that Orozco produced one of his best self-portraits. Dated 1946, this self-representation seems like it could be the painter’s official portrait; in it, he wears a coat and tie, his expression conveys maturity, and behind him appears an angled wall. The painting alludes to Orozco’s assumption of the role of State muralist and artist that had been projected onto him.

In the following pages, I will discuss in detail several works Orozco realized between 1945 and 1949, which together comprise the exhibition José Clemente Orozco: Final Cut, the exhibition featured in this publication and which explores some of Orozco’s lesser-known pictorial production. The works Orozco produced in his last period are very different compared to his work of the thirties, a time when the Jaliscan artist was more focused on making murals in the United States and Mexico. In the last years of his life, however, Orozco remained very active: he received the Premio Nacional de Artes from President Manuel Ávila Camacho in 1946 and, thanks to the poet and public official Carlos Pellicer, had his first living retrospective at the Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, in 1947.

La verdad [The Truth] (1945)

Before leaving for New York in September 1945, Orozco participated in the third exhibition of the Colegio Nacional in Mexico City, an institution he had helped found in 1943.10 In accordance with the institution’s mission to disseminate the cultural thought of the epoch, the participants were asked to hold conferences to share their work publicly. However, the painter agreed to organize exhibitions instead of conferences as a way of giving back. Thus, Orozco presented six shows from 1943 to 1948, all dedicated to his most recent pictorial work, which clearly reflected his technical, material, and thematic concerns of the time.

For the third exhibition, Orozco decided to show a group of drawings “with a broad critico-historical significance”11 that he would subsequently collect in a facsimile album published later that same year. He called the exhibition which consisted of 70 drawings La verdad, later adding the subtitle La verdad torcida, deformada, alterada, mutilada, pintarrajeada [The Twisted, Deformed, Altered, Mutilated, Daubed Truth]. In these works, it is possible to discern a much freer line, rid of academic undertones, and a prevalence of themes that interested the painter: contemporary adaptations of classical allegories, represented through female figures, monstrous images, and caricatures of violence.

Similarly, grotesque figures—tyrants, demons, hags, fools, and devils—stand out. These boast a multiplicity of perspectives and unusual visual techniques. Some drawings seem more like anatomical studies; in them, we can discern distinct movements and gestures, while other bodies seem to be contorting themselves as a way of subverting traditional artistic media.

Included in this ensemble were also some oil paintings that can be linked to La verdad. Such is the case of Escena de asilo [Asylum Scene]—also known as Escena de manicomio [Scene from a Mental Hospital], in which the painter further intensified his representation of caricaturized figures, at the same time as he juxtaposed bright colors like red with dark tones. This work seems to be in dialogue with the paintings and drawings that appeared at the fourth exhibition at the Colegio Nacional (1946), in which Orozco scathingly criticized the power, global militarism, and political corruption that he saw as the hallmarks of tyranny and despotism, especially at the end of the Second World War. Accordingly, the preparatory sketch for the oil painting Pomada y perfume [Cream and Perfume] (1946) presents a vain military officer adorned with his decorations, sitting in front of a dressing table and attended by a host of ludicrously represented people who surround him. Here, the thick lines of the drawing and the red and orange tones to which the painter would add greater nuance in the final version of the painting are striking (Pomada y perfume, 1946, Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil, INBAL).

Find this full text in the printed version of José Clemente Orozco: Final Cut here.

José Clemente Orozco, Cartas a Margarita (1921-1949), Mexico City: Era, 1987, p. 333. Author’s emphasis.

Justino Fernández, Textos de Orozco, 2ª ed., Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México-Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, 1983, p. 128.

Richard Posner, “Orozco,” in Clemente Orozco Valladares, Orozco: verdad cronológica, Guadalajara: Universidad de Guadalajara, 1983, p. 486-7.

Fernández, op. cit., p. 103.

Translator’s note: pintorcillos is a diminutive of the Spanish word pintor, meaning “painter.” While it can be a term of endearment, here Orozco uses the term derisively.

Orozco, op. cit., p. 322. Orozco refers to Inés Amor, the director of the Galería de Arte Mexicano (GAM), the first private gallery in Mexico, founded in 1935. The painter complained bitterly about group “Mexican exhibitions” that were organized in the United States thanks to GAM during these years, which served a transnational and diplomatic interest—that had grown since the twenties—in exhibiting Mexican art and culture.

Martín Acero, “El mundo a la deriva. José Clemente Orozco nos narra sus impresiones a su regreso de Nueva York,” in Clemente Orozco Valladares, op. cit., p. 494. The original comment was published in Nosotros in May 1946.

See Barbara Haskell, ed., Vida Americana: Mexican Muralists Remake American Art, 1925-1945, New Haven: Whitney Museum of American Art–Yale University Press, 2020; and Claire F. Fox, Making Art Panamerican: Cultural Policy and the Cold War, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

José Gómez Sicre, “Un gran premio para Orozco,” in Clemente Orozco Valladares, op. cit., p.521. The original comment appeared in Caracas’s El Nacional in March 1947.

The Colegio Nacional, founded in 1943 at the behest of the government, is a public institution that to this day continues to bring together notable Mexican intellectuals and scientists.

Fernández, op. cit., p. 127.

Comments

There are no coments available.