Reading time: 3 minutes

29.08.2018

Blanton Museum of Art, Austin, Texas, USA

June 30, 2018 – August 26, 2018

From the 1960s to 1980s, artists around the world participated in the profound reorientation of art known as Conceptualism. Thinking critically about entrenched traditions of draftsmanship, painting, and sculpture, artists began to emphasize the idea (or concept) behind a work of art instead of the finished object. In Latin America, this shift involved more than just a critique of art history; it was an emancipatory proposition tied to access, political urgency, and exclusion from the “centers” of art and art making. Drawing, writing, photographing, mailing, appropriating, Xeroxing, publishing, and even simply proposing work became effective forms of critique under increasingly repressive political regimes at home and against the neocolonial influence of the United States.

Drawing in the Expanded Field

In his 1962 personal manifesto, Argentine artist Alberto Greco wrote, “The artist will not teach us to see with his picture but with his finger. He will teach us to see again what is happening on the streets.” Traditional forms of art, he suggested, were insufficient to represent the increasingly chaotic, confined, and even absurd conditions of life at the time. In the decades that followed Greco’s manifesto, many artists scrutinized traditional elements of drawing—line, color, form, surface, perspective—to expand the material and discursive limits of representation. Using tactics that ranged from understatement and silence to black humor and radical poetry, they pushed their work off the page and into the street.

Off the Page and into Life

Just as they had with drawing, artists and Concrete poets pushed the limits of language to represent the world. By the mid-1970s, nearly every country in South America was governed by right-wing military dictatorships that strictly controlled behavior and speech. In the rhetoric of dictatorship, familiar words took on new, alien meanings. Artists proposed the idea that, rather than conveying a message to be interpreted by a viewer, a work of art could be activated—and thus produced—by the public together with the artist. Opening up the processes of creation and interpretation also served as a critique of the unidirectional flows of power under authoritarian regimes.

In this collaborative spirit, artists around the world began sending small-scale works on paper through the postal system, a movement that became known as Mail art. A decentralized network connecting artists on the peripheries of the art world, Mail art proposed solidarity, radical forms of communication, and distribution of art outside of institutions like newspapers, galleries, auction houses, and museums. These marginal circuits also spread information about the political situation and covertly critiqued the dictatorships’ methods of censorship and control. Mail art both concealed the sender’s message and implicated the government inthe delivery of its own critique, transforming the postal service into a conduit of subversion.

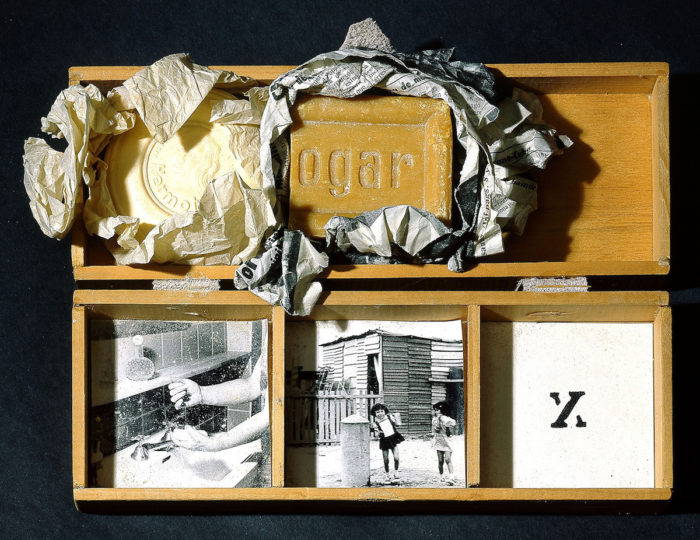

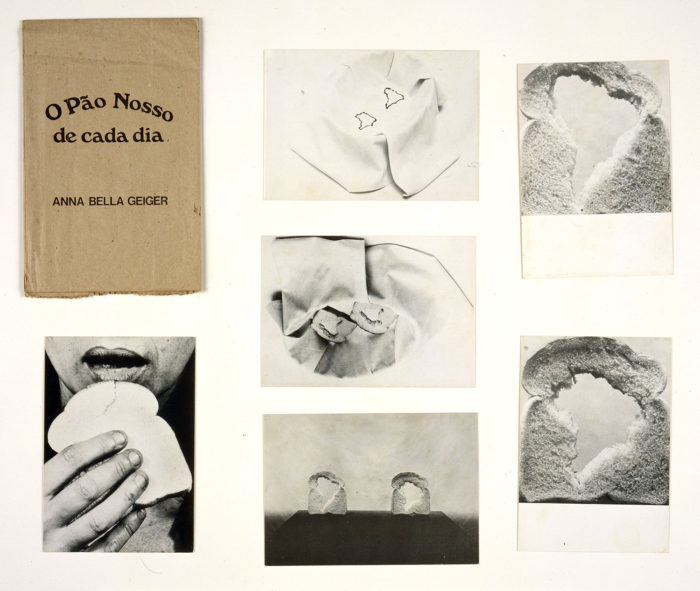

Action and Document

As members of the public became more involved in the collaborative process of art making, the role of the artist also changed. In instruction-based works, for example, the artist remains the generator of an idea or concept but delegates its actual production to others. In fact, the proposed artwork might never be made at all. Such open-ended proposals make the work flexible and responsive to its environment rather than fixed to the wall of a museum. Similarly, artist’s books invite the interpretive intervention of their readers. With pages meant to be read in any order, or acted upon, they offer a unique material relationship and a new set of meanings for each reader. Books can be sculptural or portable, accessible or easily shared. As multiples, they propose a democratic work of art in place of a unique and valuable object.

Artists, too, took part in the performative act of creation. Self-consciously and sometimes ironically incorporating their own bodies into their work allowed artists to assert their presence in history. While performative or action-based art was ephemeral and could sometimes evade censorship, many artists turned to photography and video to document and extend the life and accessibility of their critiques.

Comments

There are no coments available.