09.04.2024

Curator and researcher Sandra Sánchez visited the Bocavularia exhibition in the independent space Lolita Pank, where she interviewed the curators of the exhibition.

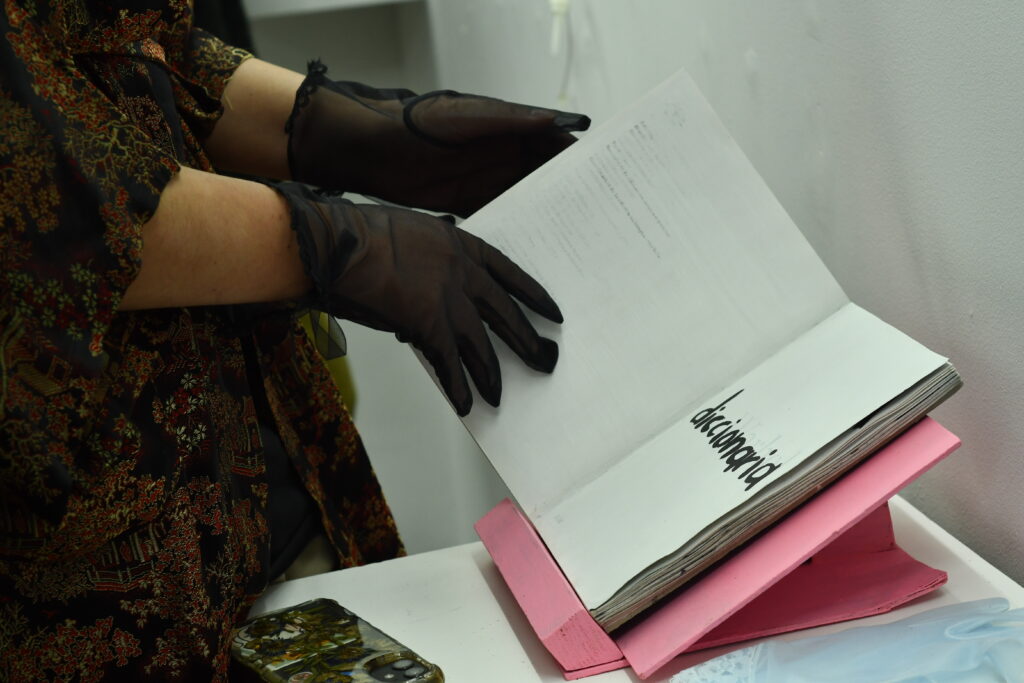

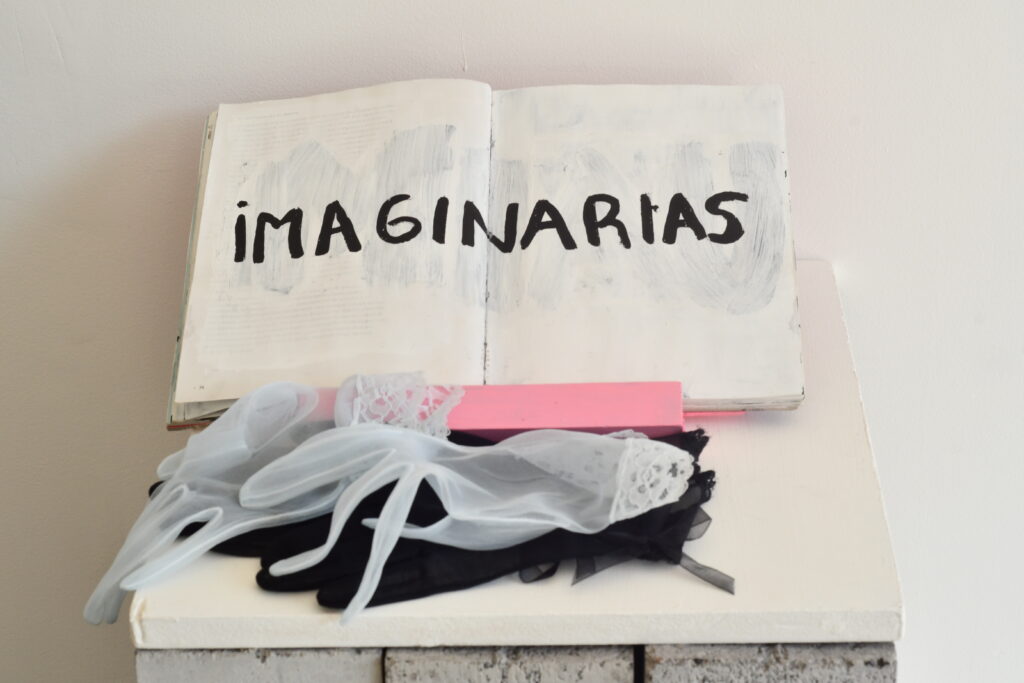

At Lolita Pank –a platform in Mexico City that connects, promotes and exhibits creative projects carried out by women and people from the LGBTIQ+ community– Bocavularia took place, an exhibition curated by Alma Camelia (from Lolita Pank) and the Argentinean Kekena Corvalan, who recently published Curaduria Afectiva (Cariño ediciones, 2023). In their words, Bocavularia is “a sudaka, Central American, Caribbean, lesbian, tortas, cis and trans corridor, which was born from an open call”.

The curators were organized with the artists Andi Garcia, Brenda Robledo, Cam Barce, Cariñas, Doble Espiral, Daira, Rocio Soria Diaz, La Betzacat, Lola Querida, Lu Pollo, Maria Silva, Marita Suavecitx, Mika Auca, Romi Vivero, Paola Ferraris, Paula Albornoz (Z), Valentina Velazquez and Tia Nuñez Caminos, to transport their work from different countries and inaugurate it at Lolita during art week. Each artist chose a letter to look up a word that would allow them to imagine, trace and exhibit their artistic practices in resonance with their daily life and/or their vitality. Below, we present an interview with the curators.

Sandra Sanchez: What were the selection criteria for this exhibition?

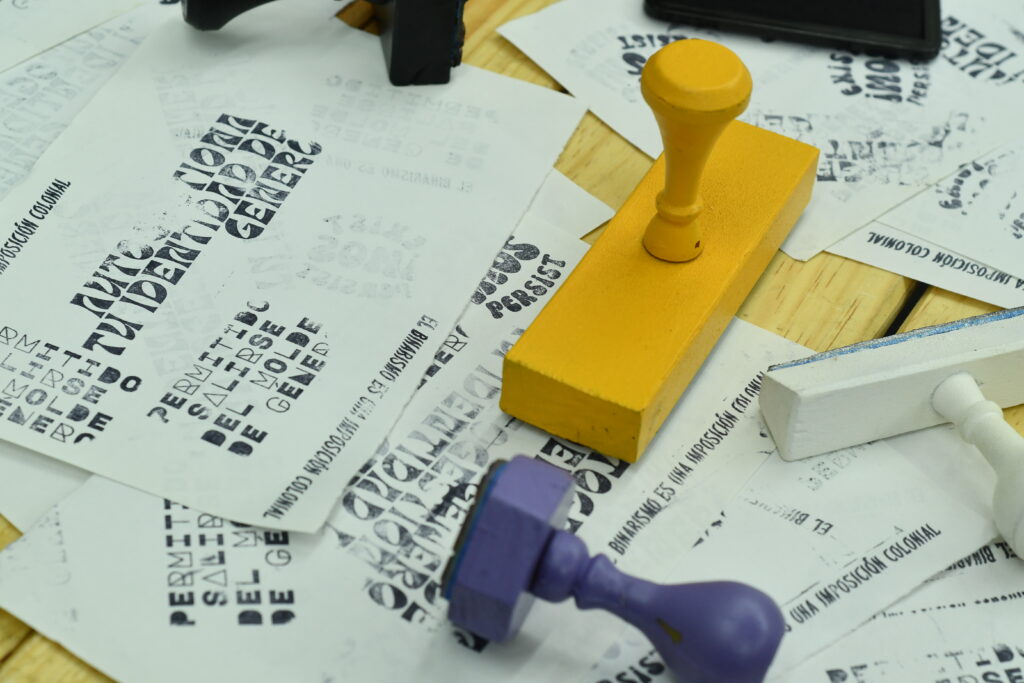

Kekena Corlavan: We did not select; we made an open call. Selecting implies a type of canon, of criteria, and that is where we are in trouble. Either there is art or there is no art. There is good art, poorly done, unhappy. That was something we had to discuss because we didn’t shed so much blood and so many tears to get one canon out of the way, one closet out of the way, and put in another. We refuse to say: “We know, in LGBT terms, what LGBT works or artists are.” It seemed to us that there couldn’t be a selection. We opened our arms and everything that came in, got in. The only criterion was the timing of the call, due to the logistics of the staging. We launched a slogan that had to do with recovering our own language. The appropriation of language is key in our LGBT and dissident fights. He who nominates, dominates. On the other hand, there is an affective statement: to gossip between us. Here, we are mostly cis, bisexual and lesbian women.

SS: There is a misunderstanding that comes from the break with the patriarchal canon, in which it seems that if there are no parameters, everything goes. How did you deal curatorially with your own limits and what politics of hospitality did you practice?

KC: For me, the limits are set by the other. The aesthetics are placed on the audience; it’s the people who come here and say: “I like it; I don’t like it”. I am not a police officer nor do I believe in taste. Taste is a political privilege. I am not a punitivist; I do not believe in castrating a rapist or punishing a criminal disproportionately. Do you know what I believe in? That we can organize ourselves and say: “We don’t like this.” We have to assemble that criterion of taste. That’s what happens here: people come and you realize that there are things they like less and things they like more. There are things that sell more. And what is sold has nothing to do with a market criterion, of a certain group that says: “This is art and this is not.” It has to do with assembling taste. When you displace the canon, love is sustained. You are not going to come and say: “This is shit.” Rather, you come and say: “I’m not going to buy this; I’m going to buy that. Tell me about that.”

SS: Does this assembling make its way into the room staging?

Alma Camelia: We all did everything. The artists who came helped put in nails, hang things, bring coffee. There was a very different logic that had to do with the organicity of the space. Even saying things directly: “Your video is not working; it is missing subtitles.” We workshopped the pieces that were not ready right here, and that is an important part of telling ourselves things; that is thinking about ourselves in relation to others.

It is very important to discuss these negotiations head-on, that is part of assembling.

SS: What a fortune to talk about discomfort without it being morally punished and reviled. I would like you to share what other types of strategies you carried out in the curatorship.

KC: The response to so much hatred that exists outside is to hold on to our affections, to take care of each other. That is the best curatorial strategy; that really heals. I always tell my students: How do you know if a project is useful or not useful to you? If your stomach hurts when you go to support that project at the museum, at the exhibition, at the gallery, at the university, it’s not useful. Curatorial policies are very territorial, very imperialistic, a matter of privilege and power; it is very difficult for love to enter there.

AC: And even more so in a field that is very competitive. We opened during an art week, in a market sense. I learned a lot because I told [the visitors] that what they were going to see were not just artworks, but something that was developed in a network of loving will. I think of a drawing that is a print because [the original] could not arrive from a province in Argentina. We put it in print because we were interested in it being there because of how it is stated, because of how it resists and continues to be painted. The works are here because photocopies were made, they were brought in suitcases, they were sent on video or because the artists traveled directly to bring the work. Different community strategies.

KC: Which has to do with different strategies of social organization. We come from feminist practices, from searching for [missing] people, from organizing for the abortion law, from school cafeterias. Territorial actions.

SS: I’m curious to know, after staging, what do you read in the works?

KC: We made eighteen artists from different countries – without sponsors and without a market – able to carry this out. It is an art of enunciation. We are not interested in the artistic statement, but rather in the enunciation. Despite the precariousness of the means, you can feel that there is work in the work; without falling into the assessment of whether something is “quality” or not. It seems to me that there is a concept that has to do with being alive. This is an exhibition that has to do with vital arts, not visual ones. There is community everywhere, everything is built with others.

AC: I would like to add that this is the first expo we do at Lolita Pank, where more people announce themselves as LGBT; it was important to me that we get to this point as a project. It’s not that it’s closed to cis people; it’s just that the audience we aimed for didn’t arrive and didn’t arrive. There are resonances between the works. For me, Bocavularia has to do with how we are appropriating our own language. Normalize our being dissident. A few years ago, it was very hostile; here, I feel like I’m assimilating an identity with what I see. What we surround ourselves with is what we normalize.

The exhibition closed on February 28, but the publication with the pieces and the Bocavularia can be consulted here: catalogo bocavularia.pdf.

Comments

There are no coments available.