Reading time: 5 minutes

30.07.2019

San Diego Art Institute, San Diego, California, USA

June 29, 2019 – November 3, 2019

Musings on a Blacktino Critical Optic

The year 2019 marks a watershed moment in LGBTQ history as museums and cultural institutions across the country commemorate the fifty-year anniversary of Stonewall, that raucous riot where queers fought back at intrepid police raids at Stonewall Inn in New York’s Greenwich Village in 1969. As with all cultural mythologies, other intermittent moments remain muddled in this historical retelling. Little regarded are the uprisings and demonstrations in California like Cooper’s Do-Nut in 1959, Compton’s Cafeteria in 1966, and Black Cat Tavern in 1967 where gender non-conformists and other queers of color rose up against police harassment.

Today as museums attend to LGBTQ visuality in numerous shows, the uproarious power of cross-ethnic solidarities and interracial affinities mustn’t be overlooked. Queers of color have served a critical purpose in art and social activism. Their creative practices—together and apart—activate San Diego Art Institute’s Forging Territories: Queer Afro and Latinx Contemporary Art, a show confronting these cultural convergences anew.

Curated by Rubén Esparza, Forging Territories stages a conversation in the historic and contemporary overlaps of queer blackness and brownness. Perhaps building on what E. Patrick Johnson and Ramon Rivera-Servera have called “blacktino,” an “optic for understanding engagements with black and Latina/o experience, aesthetics, and erotics in performance,” the SDAI show surveys twenty artists linked in a vocabulary of survival, a means of forging ahead through common matrices of ethnic objectification, police harassment, immigrant detention, and the interplay of sexual attraction, desire, and friendship [1]. It is within these intimate and sometimes fraught crossroads that the artists composing this show “converge at the margins of homonormative white culture” and thus, elucidate another territory [2]. It is a territory of self-revelatory and relational imagery, searching for definition through honest portraits and raw convictions.

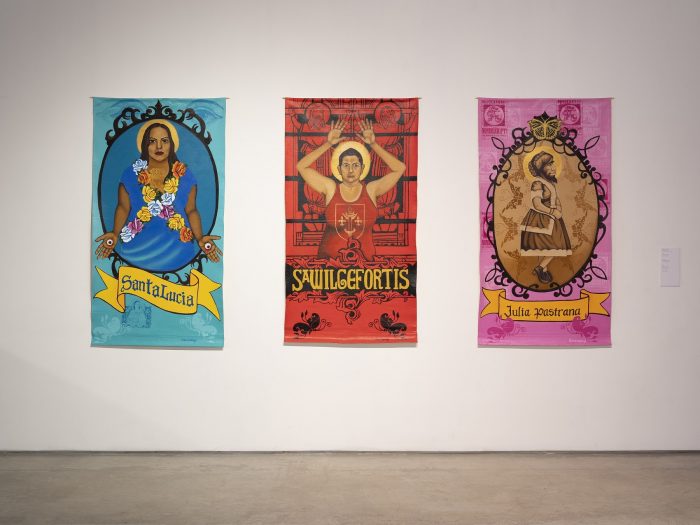

Portraiture focuses a central area of concern for queer black and brown artists in the show including the saintly imagery of Alma Lopez’s sacred Chicana lesbian icons and Amina Cruz’s candid snapshots of queer of color life. None are more exemplary than Laura Aguilar. Her photography blurs the boundaries of earthwork, feminist, and landscape imagery. With her self-nudity, she realigns natural architectural surrounds making line, form, and curve seamless. Her depiction of Latina lesbian desire broadens the terms of what is natural and what belongs. The result is a queer of color ecology, a way of negotiating sexuality, gender, and self-definition through plant matters.

Aguilar’s work complements other environmental imagery by Texas Isaiah, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, dana washington, and Maurice Harris who similarly riff on the dichotomous coordinates of masculinity/femininity, natural/unnatural, organic/inorganic in pictures undoing and remaking black queer forms. Uprooting the black nude from the fraught visual archive of Robert Mapplethorpe where floral specimens exaggerate phallic imagery of his African American sitters, these artists confront the camera and its racialized gaze. Harris’ positioning of body and bouquet, washington’s reimagining of the Garden of Eden, and Isaiah’s deeply introspective portraits of black and brown queer subjects search for another definition in the flora and fauna of self-disclosure. These are no ordinary black bodies and as Sepuya’s work further notes, they breakdown distances as interracial relations entangle in the picture frame and with the camera technology itself. He challenges the way viewers relate to queer black male bodies and thus, unsettles the eroticized contact zones rife with racialized anxiety long traced in American art history and visual culture.

Contemplating the delicacies of queer of color appearances, other works principally juxtapose hard and soft, exterior and interior, penetrability and impenetrability. Hector Silva’s graphite drawings reconstitute the solid facades of urban homeboys and barrio street thugs with sartorial codes of self-solicitation. Like Carlos Almaraz before him, Silva questions machista muscularity testing the divisions of compulsory heterosexuality and sexual ambiguity; emboldening another look at LA’s homeboys in their sexual tensions and suggestive self-fashioning. Other artists like Vinnie Garcia, Roy Martinez (aka Lambe Culo), and Nao Bustamante fancy fabrics to adorn gender variant and queer of color worlds. Like José Muñoz’s worldmaking proposal for “the ways in which performances—both theatrical and everyday rituals—have the ability to establish alternative views of the world,” these artists fabricate site-specific installations, adornments, and para-military garments and in the case of Bustamante’s soldadera Kevlar gowns, fashioning the queer ethnoracial body with bulletproof fibers for a better tomorrow [3].

The future promise of some artworks whether in the romantic parable of Denae Howard’s Black Love Story (2015) or Joey Terrill’s mid-coital Just What Is It, About Today’s Homos, That Makes Them So Appealing (2011) also necessitates reflection on our present circumstances and vulnerabilities. Currently, trans women of color shoulder the highest propensity for anti-transgender victimization and death. The fragility of life is something queers of color know all too well. As Rubén Esparza’s Pulse 49 (2017) reflects, blackness and brownness intermingle in the aftermath of twinned travesties: AIDS and Pulse nightclub. Penned in the artist’s own blood, Esparza inscribes the names of the forty-nine killed on June 12, 2016 when a shooter opened fire on Latino night at Pulse, the Orlando nightclub. With twenty-three slain of Puerto Rican descent, the horror of that moment echoed the increased exposures of violence and brutality that black, brown, and Afro-Latinx queers have confronted transnationally stretching from island to mainland. Listed in a format rising from the bottom region of the page, Pulse 49 eerily reflects the enlisting of names in a manner reminiscent of the AIDS crisis. Although there is no end to the dying with people of color representing the highest rate of new HIV infections presently, Esparza returns to a familiar AIDS memorial vocabulary and births these names in the plasmic fluid made lethal in AIDS phobic discourses. Esparza bears on this moment of AIDS history and cross-ethnic queer performance art to forge new territory. Thus, he commences a language of loss that a blacktino queer optic makes possible.

—Text by Robb Hernández, Ph.D., Associate Professor, University of California, Riverside

—

Artists

Laura Aguilar, Carlos Almaraz, Patrisse Cullors, Texas Isaiah, Devin Morris, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, dana washington, Nao Bustamante, Amina Cruz, Angel Divina, Rafa Esparza, Vinnie Garcia, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Maurice Harris, Danae Howard, Alma Lopez, Roy Martinez, Devin N. Morris, Joey Terrill.

—

—

[1] Johnson, E. Patrick and Ramón H. Rivera-Servera. “Introduction: Ethnoracial Intimacies in Blacktino Queer Performance.” In Blacktino Queer Performance, edited by E. Patrick Johnson and Ramón Rivera-Servera, 1-18. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016.

[2] Ibid., 6.

[3] Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Comments

There are no coments available.