13.05.2017

by Patricia Restrepo, Houston, Texas, USA

March 5, 2017 – May 21, 2017

The debut presentation of Adiós Utopia: Dreams and Deceptions in Cuban Art Since 1950 at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston (MFAH) is the most comprehensive and (self-declared) significant presentation of modern and contemporary Cuban art shown in the United States since 1944, when Modern Cuban Painters was mounted at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Given the exhibition’s superlatives coupled with the recently shifting yet tenuous relations between the U.S. and Cuba, I did not doubt the relevance or importance of this exhibition. Yet, despite some of the show’s strong singular works and innovative curatorial techniques, including incorporating historical photography, Adiós Utopia contains conspicuous absences and presents a one-dimensional and simplified Cuban history. Ultimately the show has shortcomings of a nuanced perspective regarding the arc of Cuban history, as it does not provide a space for alternative and compelling narratives.

First, let’s explore the who’s who of this exhibition, as the exhibition had to manage differing agendas. Adiós Utopia was envisaged by the Cisneros Fontanals Fundación para las Artes (CIFO Europa) and the Cisneros Fontanals Art Foundation (CIFO USA), curated by three Cuban independent curators—Gerardo Mosquera, René Francisco Rodríguez, and Elsa Vega—and organized in partnership between the MFAH’s prestigious Latin American Art Department and the Walker Art Center. The featured artists were born in or based in Cuba at some point, although the specific parameters around inclusion are not clearly delineated.

The ingress to the show did not disappoint. Ascending to the top-floor of the Mies-van-der-Rohe-designed building, I was greeted by Wilfredo Prieto’s Apolítico (2001), a work that constitutes 30 monochromatic flags, all devoid of their differentiating, nationalistic coloring. I next approached the exhibition’s section dedicated to revolutionary poster art. Despite some installation issues, the posters themselves are a stunning visualization of the potency of the revolutionary spirit and its ability to harness aesthetic potential and graphic innovation to disseminate political messages. Including over 50 designs by designers like Olivio Martínez and Antonio Fernández Reboiro, these posters remained some of the most visually potent works in the show.

Neighboring the posters, the show’s introductory text established its context and significance. It made claims including that that the exhibition was not going to be a straightforward chronological show but instead focus on thematic connections present in over 65 years of work. The show united over 100 of works of painting, graphic design, photography, video, and installation created by more than 50 Cuban artists and designers. The text also asserted that it was going to focus on the untold narrative of Cuban artists. As the educational materials stated, “Adiós Utopia introduces U.S. audiences to key events in Cuban history and explores how this history affected individual artists, shaped the character of art produced on the island, and conditioned the reception of Cuban art both in Cuba and abroad.” We, in turn, must ask how this exhibition in specific can condition the reception of Cuban art, and more significantly although less explicitly, the reading of modern Cuban history.

The show opens with a stunning sampling of 1950s Concrete art, establishing from the onset Cuba’s lineage of cerebral art. Although these non-figurative works play with geometric abstraction, they were infused with political ideals by many of their creators, notably by Los Diez Pintores Concretos (Ten Concrete Painters). This group sought to establish new realities within the innovation of their work; within a few years, they shifted abstraction from a realm of non-representational work to a conceptual field that could be employed for political and social ends. Of particular interest were works by Romanian-born Sandú Darié. His estructuras pictóricas (pictorial structures) allowed him to explore the premise of framing and its relationship to space. Despite the exhibition’s aim to present works thematically rather than chronologically, this room establishes the show’s predominantly chronological sweep with token anachronistic works. The outlier contemporary work in this room was Yaima Carranza’s video Malevich, de la serie Tutoriales de esmalte de uñas [Malevich, from the series Nail Polish Tutorials] (2010). Didactics associated with this video piece already lay the groundwork for the ultimate conclusion of Cuba’s failed utopia by stating that this video demonstrates “the gaps between revolutionary ideals and reality.”

The next room traced the formation and use of Cuban revolutionary ideals and icons, such as the Cuban flag. A relatively straightforward room, the space was elevated by the chronological outlier work of Juan Francisco Elso’s For America (José Martí) (1986), a sculpture depicting the revolutionary leader José Martí as a religious martyr. A curatorial strategy employed in other rooms on a smaller scale, the inclusion of historical photographs alongside works of art is introduced here. Iconic photographs by Alberto Korda, Raúl Corrales, and other documentarians of the 1960s are brought into a democratic dialogue with related artwork. Historical photography is sprinkled throughout the exhibition, allowing work that is usually subjected to the role of documentation to be viewed as artwork charged with iconic and symbolic meaning.

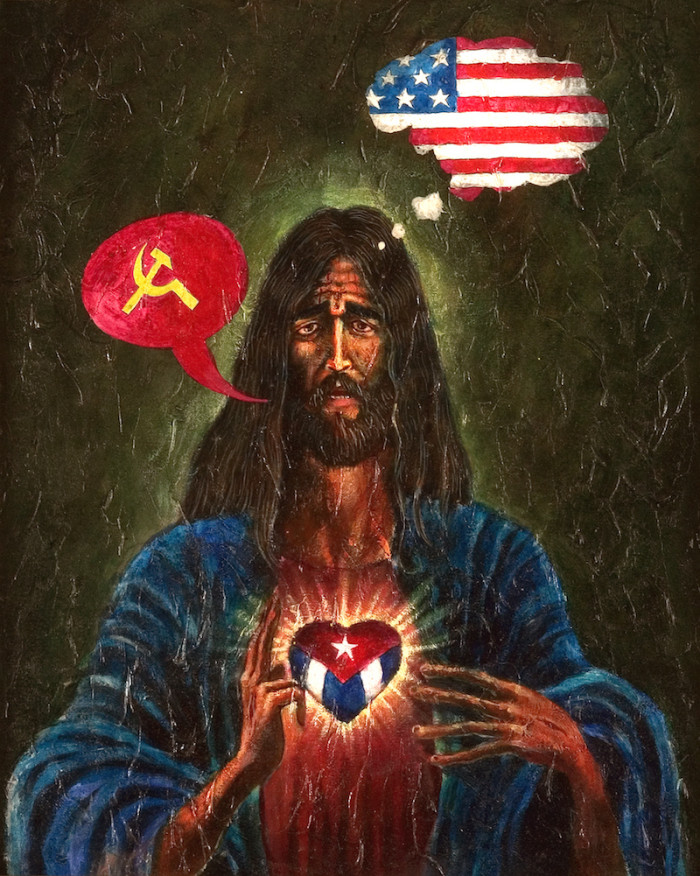

The following space proceeds to deconstruct revolutionary ideals. Not all of these works can be read as critical of the State; instead, they exemplify manifestations of artists’ dialogues with the government. Playful drawings by the artist-duo Eduardo Ponjuán and René Francisco refreshingly utilize humor to demonstrate some of the absurdities and contradictions of Cuban politics in the 1980s. This room also contains the only work that overtly references the United States: Lázaro Saavedra’s El Sagrado Corazón [Sacred Heart] (1995), which features a version of the Sacred Heart of Jesus in which the heart figure is filled with a Cuban flag; his speech bubble filled with the Communist hammer and sickle, and his thought bubble containing the U.S. flag.

The exhibition then explores the role of words: for example, how speech shaped revolutionary ideology and the impact of governmental censorship. With its literal explorations of Cuban political chambers and a device to monitor censorship, the first room was too straightforward; refreshingly, the second room explores metonymic representations of media through visceral representations of parts of the mouth. Umberto Peña’s brightly-colored and grotesque works were highlights here. Nestled between these spaces is a room that alludes to themes that I wish had been teased out more: Cuban suffering caused by U.S. governmental policy, as well as the instability of Cuba’s future given looming foreign investment. Tonel’s installation El bloqueo [The blockade] (1989) is comprised of a set of cinder blocks forming the shape of Cuba, above which threateningly sits the phrase “El bloqueo.” Although I read this as a criticism of the U.S. and its efforts to throttle the Cuban people, the didactics of the exhibition boldly said that it could reference Cuba’s “self-blockade.” Additionally, while I wish it had been further expanded upon in the show, the creation of an increasingly neoliberalizing force in contemporary Cuba is briefly touched upon in Reynier Leyva Novo’s Nueve leyes [Nine Laws] (2014). This piece visualizes the area, volume, and weight of the ink in handwritten and printed key pieces of legislation passed by the Cuban government. This piece has a compelling reference to Cuba’s future with a representation of the 2014 Law of Foreign Investment. This work, which spans two large walls with ample breathing room, is also a beautiful echo of the Concrete work presented in the first room.

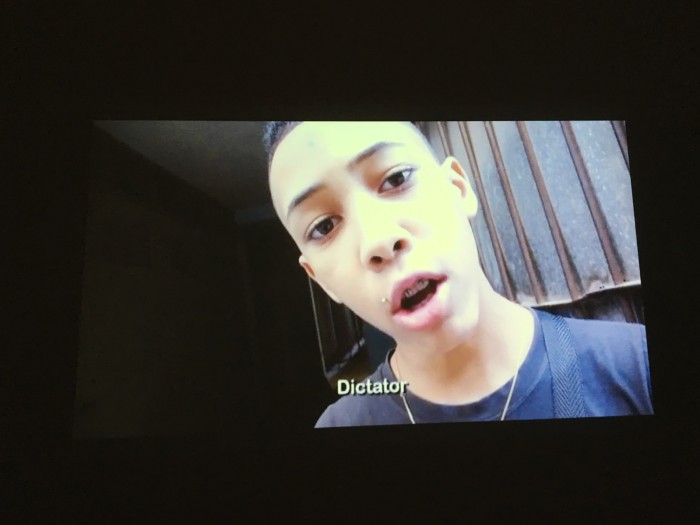

The show concludes with explorations of “lost illusions and inverted utopia.” For me, the handling of this theme weakened the exhibition. Many works used inverted symbols of the Revolution in the most literal sense; it was too easy, too obvious, and too one-noted. Los Carpinteros’s Faro tumbado [Felled lighthouse] (2006), for instance, sculpturally depicts Havana’s iconic lighthouse turned on its side, loudly hinting at the parallel of the fallen Castro regime and its Communist dream. There is also an ominous oil-filled sculpture by Yoan Capote (that was unfortunately non-functioning during my visits), as well as photographs of abandoned sugar-related industrial sites by Ricardo G. Elias. Glenda Leon’s more ambiguous work Añoranza [Longing] (2004) is a welcome reprieve from heavy-handed messaging; a butterfly with its wings held back is mounted on the wall above my head. Are the wings trapped, literally unable to fly from externally imposed limitations, or is the moth just beginning to emerge? We aren’t given an answer. Despite a few breaths of fresh air, there is no doubt that this final thematic is about Cuban artists’ discontent with their context. Javier Castro’s charming video La edad de oro [Golden Age] (2012) contains the dreams of Cuban children included two wishes to be a “foreigner” and one dream of being a “dictator.” The video presents a rather gloomy future in terms of children’s prospects. Within the thematic of the exhibition, the video is a tied perspective of the dreams and wishes of Cuban people.

By the end of the show I was teeming with questions. Why is this work displayed here? I felt that this exhibition was an excellent opportunity to deal with works that approach the United States critically—its history of questionable interventions and current dollar-thirsty investors (including art investors). Likewise, I thought it was necessary to carve out more spaces for works that present alternative perspectives exploring the past and present of Cuba outside of the Revolution, as it is the case of René Francisco’s Fábrica de utopias (2014), for example. Where were the works that attempt to revive romantic aspects of this Revolutionary past while acknowledging disenchantment with other aspects, such as the poetic actions by Felipe Dulzaides in his project Utopía possible (1999 – ongoing)? One also felt the absence of Wilfredo Lam, as well as the exploration and significance of Cuba’s ambitious and visionary National Art Schools project, Instituto Superior de Arte, which has generated a great amass of artistic talent and serves as an apt metaphor for Cuban revolutionary history. Finally, there is a lack of works that explore the complex Cuban racial landscape, such as the Queloides project. The only work that hints at the mosaic of racial identities in Cuba was Tania Bruguera’s stunning Estadística (Statistic) (1995 – 2000), a Cuban flag composed of human hair weavings.

Clearly, this deluge of concepts is far too expansive for any single show; yet for me, a more nuanced presentation would have resulted in a more complex and compelling telling of this Cuban history. It is clear that Adiós Utopia has a thesis that is overtly represented but not explicitly stated: each room seemed to continue the arc of the show towards a demonstration of the Cuban Revolution as a failed experiment. The title itself reads as an obituary for the passing of the revolutionary attempts. Ultimately, how could a U.S.-centered exhibition of Cuban art not be political on levels beyond the political art contained within the exhibition itself?

Although the exhibition is riddled with setbacks that make it difficult for it to achieve some of its lofty objectives, this exhibition does allow visitors to engage conceptually with art to which they do not normally have access, allowing us to see Cuban conceptions of their nation—caveat: carefully-selected conceptions—rather than the known U.S. notions of Cuba.

Comments

There are no coments available.