Writer Devon Van Houten Maldonado speaks with curator Modou Dieng and artist Hank Willis Thomas about identity, race, migration and globalization from an afro descendant perspective.

To mark the inauguration of Transparency Shade at projects+ gallery in St. Louis, Missouri in April, 2017, curator Modou Dieng, artist Hank Willis Thomas and I pieced this dialogue together from live interviews and email conversations. The text below adds to an exchange Dieng and I have been engaged in since 2011, having worked together on several exhibitions and a major project for the 2014 Portland Biennial, and which we took up anew after several years when I’ve been living and working in Mexico City while Dieng traveled between Africa, Europe and the United States. It was a tremendous privilege to benefit from Hank Willis Thomas’s insight and formation as a celebrated African American artist from the United States. As you will read, Dieng and Willis Thomas have also been engaged in an ongoing years-long conversation about the topics below: migration, hybridity, exoticization, authenticity and globalization.

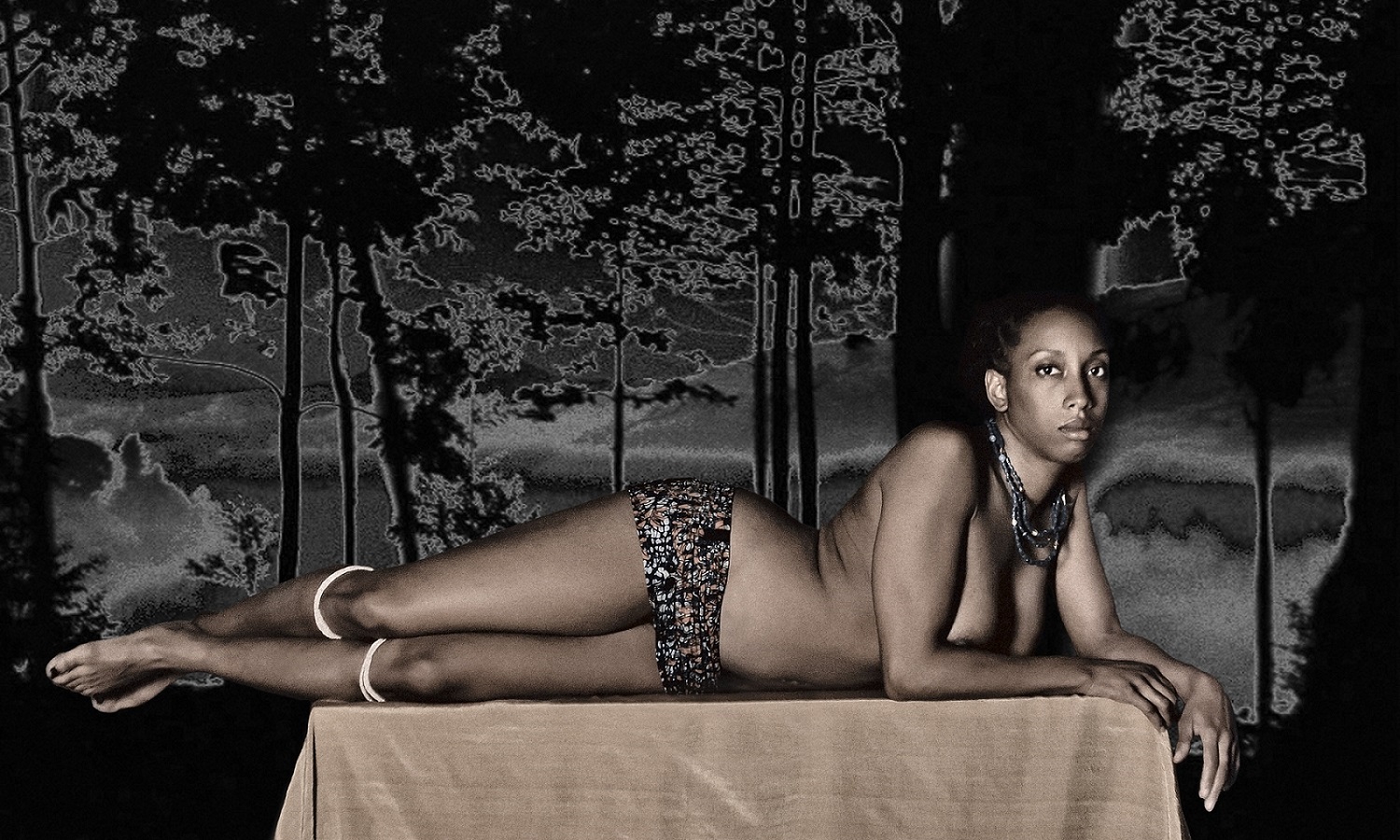

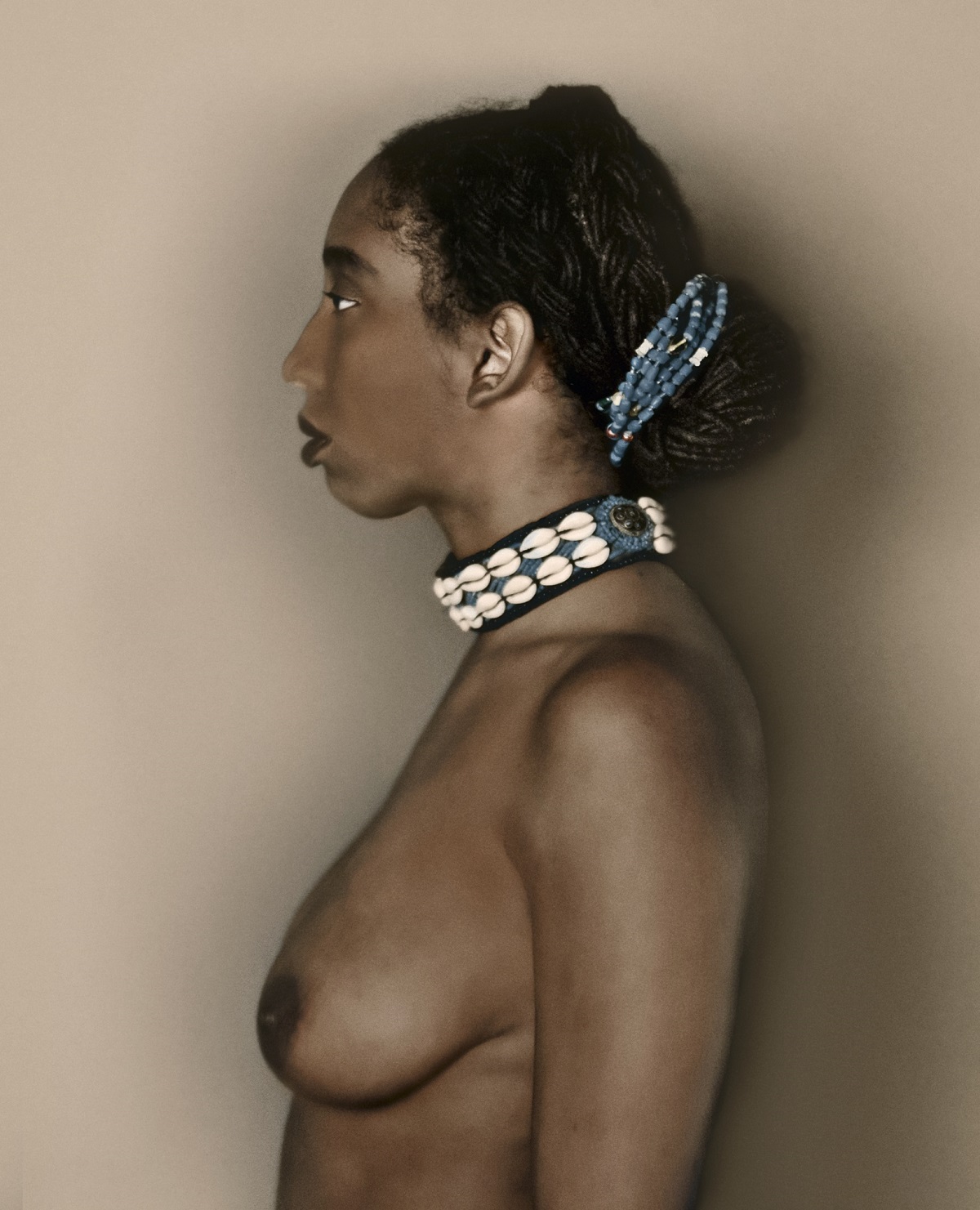

The other artists featured in Transparency Shade are Philip Aguirre y Otegui, Zoe Buckman, Kendell Carter, Kahlil Irving, Ayana V. Jackson and Michael Riedel. The show in St. Louis, where the heaviness of the events in Ferguson, just a few miles away, dominate the landscape, and which provided the context and backdrop for our dialogue, features a diverse and transcontinental group of artists who, brought together by the curator and artist originally from Senegal, engage in a conversation about hybridity and diaspora. But the artists here also forge hope for new polycultural epistemologies. For Terremoto’s After Brazil issue, the future is at the front and center as we imagine possible utopias and dystopias emerging from the post-anthropocene and wonder what catalysts exist in artists studios from Mexico City to Dakar, from New York to São Paulo.

Devon V.H. Maldonado: How do you, as an African artist (Modou) or African American artists (Hank), working with other diaspora and/or international artists, think about the tagline and subject matter of this show: “post-identity semiotics”? What’s identity when who we are as individuals is confused and caught up with consumerism, racism and lasting colonialisms? What is post-identity?

Modou Dieng: The way we perceive identity has been so affected by globalization in the 21st century. Thinking about being an African artist, having the opportunity to travel all over the world all the time, is insane. When you think of the first moment when artists from the third world had the opportunity to travel, it was in the late 90s when the biennial phenomenon started. It was so hard to get work shipped from third-world countries that artists would just travel to make the work wherever they were going to do the exhibition. That created this new perception, not only for third-world artists, Africa included, but also artists from other places in the western hemisphere, realizing that these people are not of that exoticism we were talking about. They actually have critical thinking, they have new ideas, and they want to go beyond the stereotypes, beyond the parameters of nationalism.

Hank Willis Thomas: I think my first interaction with Modou about 13 years ago at my first solo show in San Francisco is how this conversation started. He questioned me about my representation of “blackness” being so America-centric. At the time, I wasn’t comfortable with speaking to African continental and African Diaspora experiences outside of the U.S. Modou challenged me to think more globally and I have spent much of my career trying to improve my own capacity and comfort in the area. When it comes to discussions of “blackness” (quotations intended), there is often a U.S. American hegemonic orientation that’s not only simplistic but inaccurate, unproductive and unhealthy. The question for me is, how do we shift the focus of the lens, make it wider angle and get more cameras?

DVHM: How do you think the idea of migration, utopia and race is playing out in art and in the artist’s studio, and what do you think the future of these will look like?

MD: I’m a generation-x African: I was born in the 70s. We learned to discover the world through the radio, through the short waves, through BBC radio, or through Radio France Internationale. There was this sort of love of the unknown of this new territory, of this new horizon, which was Europe and America. America was this really emblematic beautiful sound that comes from African-America to tell us about the blacks in America, to tell us about jazz, funk music, rock & roll, Elvis, James Brown. It was such a beautiful moment in my upbringing, being in Africa and discovering the world through the radio, through culture, music, and art. Of course, my dream was to join those people, those territories, to join that culture and be part of it and make something new.

I wasn’t thinking of migration as a problem, it was more of a solution.

HWT: I think this is a peculiar moment. Global forced migration has reached a level of media exposure that we haven’t seen in our life times. I think “race” is increasingly proving itself difficult to codify, police and enforce: a second-generation Syrian immigrant in the United States is “white” while a recent Syrian immigrant is “Arab”. The United States is becoming more visibly culturally diverse. What the term “American” describes will certainly be different in 20 years than it is today. Progress is being made so rapidly that some people want to jam on the breaks and hit reverse. Sadly they don’t understand the laws of physics: the outcome will be that culture will flip over itself and fast forward just like it did in the 20s after the repression of the 1910s and in the 60s after the cultural repression of the 1950s. While some are covering their eyes and screaming at the driver, many of us are busy fastening our seat belts.

DVHM: Considering what you’re saying about migration as a solution, Modou, I’m interested in what you think about maintaining the integrity of difference, considering the globalization you were talking about, as well as mass media, migration with racial, cultural and literal barriers continually broken down—how do we maintain the integrity of our differences?

MD: What do you mean by integrity of difference? Are you talking about authenticity? What is authentic?

DVHM: I’m asking you—when I say the integrity of difference, I’m talking about the impacts of globalization, war, capitalism and neoliberalism as homogenizing forces. In hybridity there is also the danger of homogenization, and even the homogenization of culture, which ties into tradition and tradition being used to exoticize. How do we maintain the preciousness of our differences?

HWT: I don’t believe in collective difference. Difference is always individual and temporal.

That’s what conservatives ask all the time. I say the road to progress is always under construction. Save what you will, but it might be soon become a relic. Start writing and telling its stories now to preserve its value. The future has a lot to learn from now. What gets preserved matters, but we can only control a little bit of it. It’s on us to advocate for the things we value, but not pretend that any cultural tradition has ever been pure. They have always been hybridized and changing. The only difference is that we now have mediums to record and be nostalgic.

MD The question is really: do we need to take authenticity as something coming from modernity, from tradition, or from contemporary life? When I think of migration as a solution, I’m thinking of it as a way of engaging a conversation with a different culture, as engaging yourself within a new place, new inspiration, new ideas, and to bring that together to make the world a more understanding place.

Léopold Senghor, the poet who became the first president of Senegal, said, “Civilization of the twentieth century cannot be universal except by being a dynamic synthesis of all the cultural values of all civilizations.” Which means the meeting of the universe is around taking and giving in terms of culture, in terms of hybridity. If you think about hybridity, even having a hybrid car is supposed to be better, right? To have a sustainable ecosystem. That hybrid dialogue that migration is creating—I don’t think it’s a danger to authenticity, nor a danger to antiquity. People still remain who they are. The mystique of traveling; to create a conversation around different places, different people. What’s so amazing about going to China, for example, is discovering the mystique of Chinese culture.

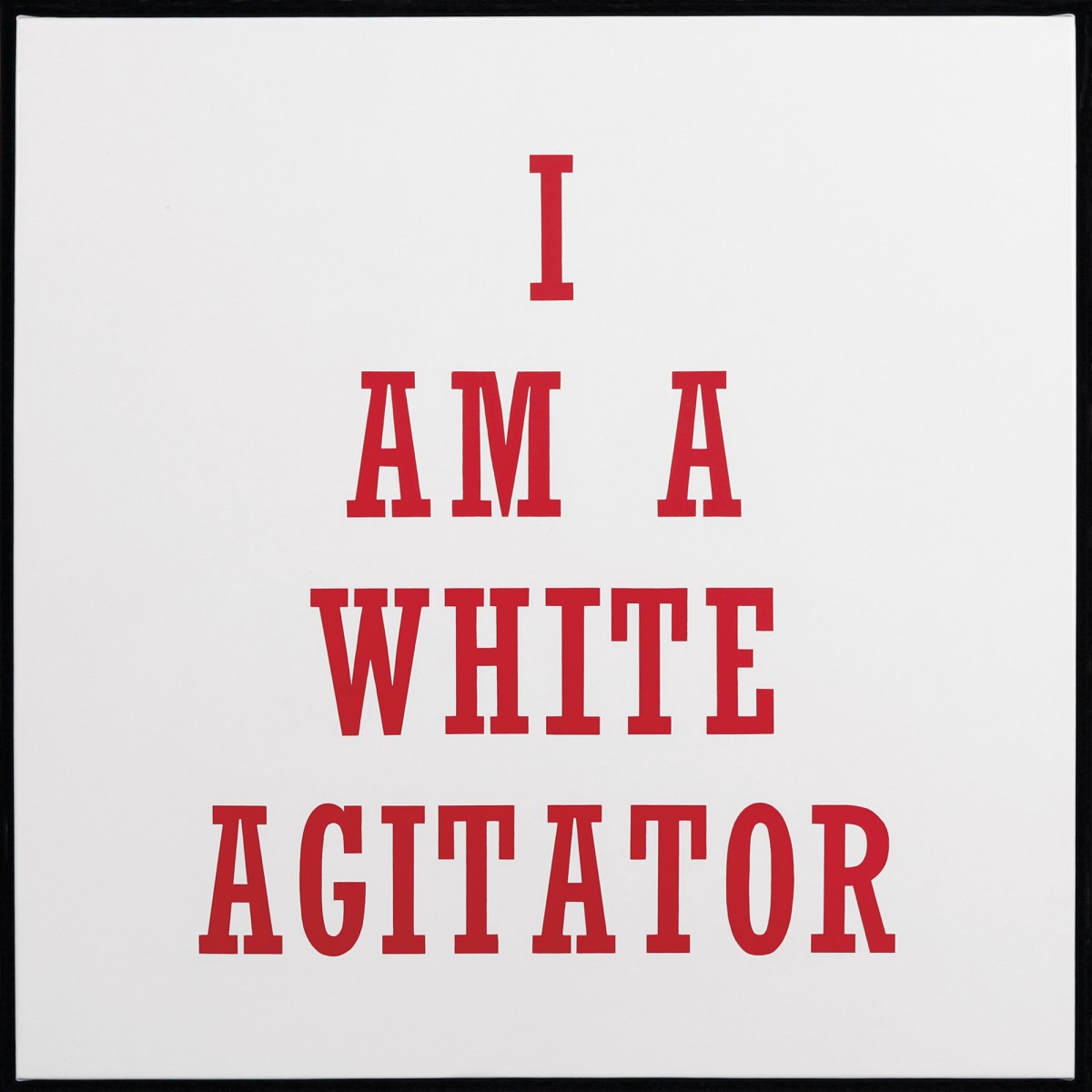

DVHM: When you walk into the gallery, the first work you see as part of the exhibition Transparency Shade is Hank’s painting that says, “I am a white agitator.” Considering our conversation and the context of the show near Ferguson, where apocalyptic images of ongoing civil rights battles play out on mainstream television, what is a “white agitator”?

HWT: During the protests against segregationist Alabama governor George Wallace in the 1960s, the Communication Workers of America labor union created a pin-back button in response to his argument that “black” people were totally fine with racial segregation. He argued that it was outside “white agitators” causing trouble among the local population.

He once wrote: “White and colored have lived together in the South for generations in peace and equanimity. They each prefer their own pattern of society, their own churches and their own schools—which history and experience have proven are best for both races. (As stated before, outside agitators have created any major friction occurring between the races.) This is true and applies to other areas as well. People who move to the south from sections where there is not a large negro population soon realize and are most outspoken in favor of our customs once they learn for themselves that our design for living is the best for all concerned.”

DM: Then it became a picket sign and this was the first time it has been done as an artwork. So it’s an appropriation of history and culture.

DVHM: It’s also this sort of declaration.

HWT: It’s an ironic reclamation and appropriation of a term that was intended to discredit and shame.

MD: Yes, today it could mean different things because of what’s going on.

DVHM: Also because a person of color saying, “I am a white agitator,” takes on a totally different meaning.

HWT: Funny, I didn’t read a “person of color” saying it. But that does make it better.

MD: I think the art world, and the way we are forced to work in the art world from our studio, needs to be desegregated. I think we are segregated. Why do we have only African American artists talking about issues around African American culture? Why do we have whites only talking about mainstream culture or modernity? Why do we have African’s only talking about Africa? What’s the point of that?

DVHM: Going back to migration, the terrible conflict in the Middle East tends to dominate the media and our imaginations, but there is a conflict closer to home, the huge crisis happening in Honduras, El Salvador and Venezuela. There’s a giant migration from South to North in the Americas. If you’re somewhere in Latin America or in the Americas outside of the United States and you say you’re American, they will respond by saying “America’s a big place.” In Spanish, estadounidense (someone from the United States) and americano (American) are two different things. But we have this naval gazing idea that the Unites States is America, which Hank alluded to when he talked about the challenges of addressing African continental and African Diaspora experiences outside of the U.S. We think about it like this utopia, when it might be more like a dystopia. What do you think about the future of the Americas as an entity, the Americas as a whole entity?

MD: The way I see it, it’s way more interesting for the north to go south than the south to go north right now. When you think about Cuba opening up and you have the Havana Biennial, Material Art Fair in Mexico City, and also the Sao Paulo Biennial.

HWT: One day nation states will be irrelevant again. I have no idea what is next or what to think of it.

DVHM: But there is still this exoticization of the south.

MD: Yeah, but now we have the Hong Kong fair, why? Because there’s billionaires in Hong Kong and it’s exotic and beautiful.

HWT: Us is them; they are us.

DVHM: So exoticism isn’t always a bad thing.

MD: No, I think exoticism is a great thing! Because it goes against homogenization, thinking about globalization as one thing that we all have to absorb from the western hemisphere and culture, and I think there is something very exotic and beautiful, something amazing, coming from South America, from Africa, from Asia, that we need here in the Western World. We just need it: it’s the food, it’s the culture, it’s the style, it’s the fashion, and it’s the beauty. I’m not saying it doesn’t exist here but it’s fascinating because it’s not homogenous. Maybe it wasn’t a great thing 50 years ago, when those traditions were treated as second or third class. But today with education and globalization everywhere, I think we need to rethink what exotic means.

HWT: Something we don’t know is always exotic.

DVHM: We’ve touched on tradition a little bit. In spaces where capitalism and modernity hasn’t run rampant, we still have thousands-of-years-old traditions. In the West what we have is the idea of “progress”, and all of our discourses in the West are about moving forward through linear time and making progress. Outside of the West the dialogue is about tradition. But it is a static tradition that keeps those spaces stuck in time, and epistemologies that don’t think of time as linear are erased or appropriated and absorbed. How can tradition be dynamic and evolve?

HWT: Time moves differently for different people and especially in different places. No one controls the clock: the best we can do is watch it.

DM: Capitalism isn’t a culture; it’s a system for profit. A system around profit tends to remove culture. The value of tradition, what tradition does, is to keep the value of culture in the conversation because culture is older than us. Culture is older than a lifetime; profit might not be. Exoticism is just a culture. How do we preserve nature within culture? How do we preserve the people within nature and culture? What does capitalism do to those elements of life? I think that is where progress comes as a real question and where culture comes as a real value. Is it progressive to robotize everything? Yeah. But is it culturally relevant and good? No. I think those two things have to sort of create a balance for each other and survive our own need for benefit and profit.

DVHM: In the Americas, because of what they call “the Colonial wound”, the critical conversation around art has a constant reference to colonization and to class differences. It gets played out again and again, and its inescapable in these places, but at the same time that conversation is used to segregate and separate, and it also becomes didactic without offering productive solutions for rescuing freedom back from forces of imperialism. On the other hand, in Europe for example, the work tends to deal with technology and futurism, imagining techno-utopias and dystopias.

At the same time, there is a beautiful connection with science fiction, Afro futurism and feminism as spaces where new creativity and new epistemologies can be created or revolutionized. Now we’re moving into a space where the future is ours to create. How do we use these movements to get over these segregations?

DM: Having been colonized myself by the French, I think about colonization as something that didn’t just happen within the last three or four centuries. It happened through time. Many people from many places colonized many people of many places. The last leg, which is what we know, is the last four or five hundred years and it was more of a Western colonization. We have to go beyond colonization and make it a post, make it a past and see what’s beyond that. How do you transcend this necessary evil to become your own culture: to repackage, to re-appropriate, to retake your own value and culture and make it a new thing of the future? Maybe that is where Afro-futurism plays in. We talk about the Afro as this beautiful fictional land that we can play with and transcend the horror and the struggle of our African-ness and our blackness. What about the future of Afro?

HWT: Imperialism doesn’t die. It retreats and reforms. Human nature is to assert and dominate. It is this self-destructive tendency that we have to mind. It will ultimately lead to our demise. It has happened in the past several times. It will happen again. If we believe in “race” we are racists. It is a divide-and-conquer strategy designed to keep us in competition with ourselves for the temporary profit of few. We are all poisoned with the illusion of racial difference. The problem is that no one ever can win the race; we can only get tired of running.

Comments

There are no coments available.