Issue 14: Look Who's Talking - Peru

Natalia Majluf, Beverly Adams, Florencia Portocarrero

Reading time: 12 minutes

04.03.2019

Florencia Portocarrero, co-editor of this issue, talks with curators Beverly Adams and Natalia Majluf about «Amauta» magazine, which, during the 1920s, inaugurated a circulation of ideas and discussions about what Latin America could have meant in relation to Marxism and the avant-gardes of Western modernity.

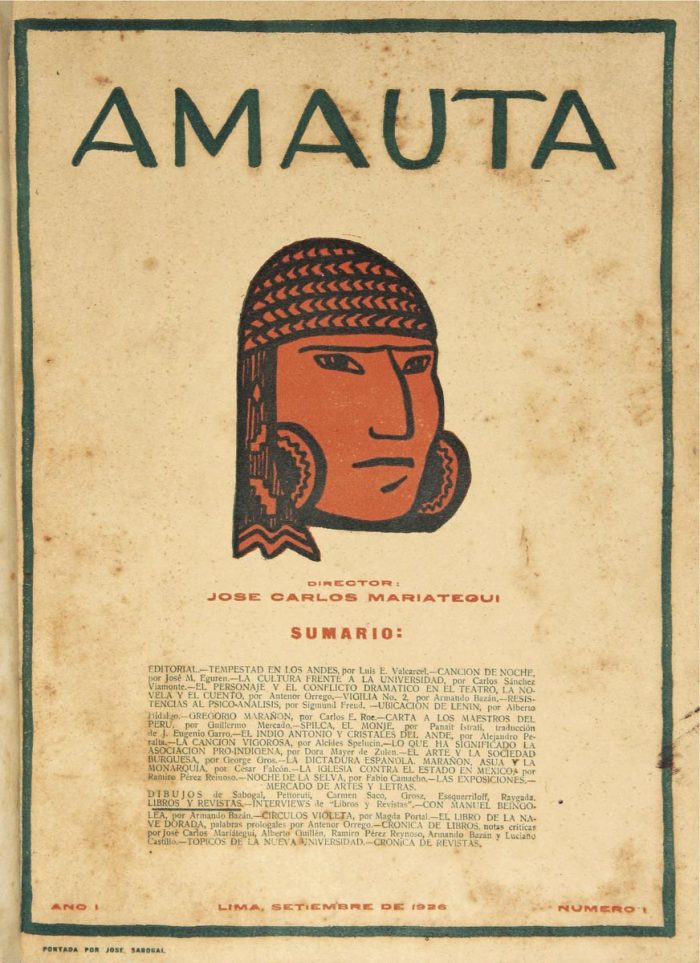

The Peruvian magazine Amauta (1926-1930) was one of the most influential avant-garde publications of the twentieth century. Directed by José Carlos Mariátegui [1], father of Latin American Marxism and a member of the Partido Socialista Peruano [2] [Peruvian Socialist Party], the magazine quickly became a space where the American political and cultural vanguard could coincide. Amauta—which in Quechua means teacher—was a collective generational project that sought to renew the Peruvian national imaginary, promoting pro-indigenous and socialist values in a context in which oligarchy and foreign capital perpetuated the colonial order at an economic and social level. Starting from the revindication of Andean collectivist traditions of millennial origin—and proposing them as the substrate for a modern communist, as well as Latin American, movement—the magazine sought to articulate the discussions around the different movements of social transformation for the creation of the continent.

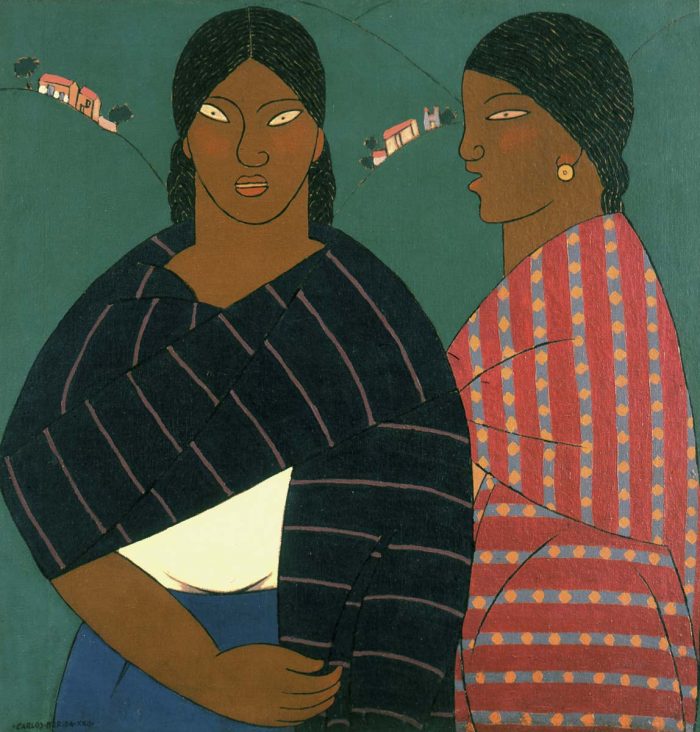

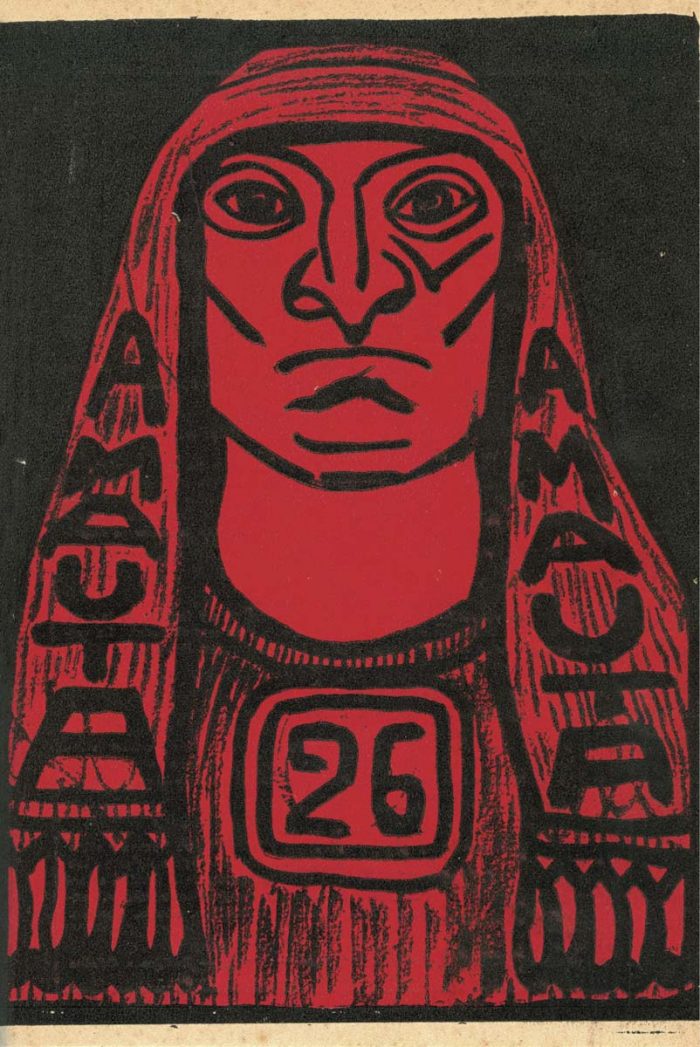

Indeed, Amauta was indispensable to create a new ideological environment in Peru and Latin America. Throughout its 32 issues, the magazine managed to bring together the most progressive artistic expressions and ideas of the time. Marxist analysis converged in its pages along with concerns that arose in indigenist circles, reflections on the artistic vanguards, and even founding essays of psychoanalysis. Through a non-negligible circulation (between three and four thousand copies) and an extensive and heterogeneous network of agents and correspondents in Latin America and Europe, Amauta managed to strengthen its scope and international impact. Redes de vanguardia: Amauta y América Latina, 1926-1930, an exhibition curated by art historians Beverly Adams (curator of Latin American art at the Blanton Museum of Art, University of Texas at Austin) and Natalia Majluf (who just left the leadership of the Museo de Arte de Lima, MALI), examines the decade of the 1920s from the perspective of the magazine. The exhibition brings together 300 contemporary works to the show, covering various media and formats: painting, drawing, sculpture, photography, popular art pieces, and archival documentation. Among the artists represented in the exhibition are Ramón Alva de la Canal and Diego Rivera (Mexico); Camilo Blas, Martín Chambi, Julia Codesido, Elena Izcue, César Moro and José Sabogal (Peru); Norah Borges, Emilio Pettoruti and Xul Solar (Argentina); Carlos Mérida (Guatemala) and Tina Modotti (Italy).

Redes de vanguardia: Amauta y América Latina, 1926-1930 opened on February 20, 2019 at the Museo Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid and later will travel to the Museo de Arte de Lima (June 20 – September 22, 2019); the Museo del Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (October 17, 2019 – January 12, 2020) and the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas (February 16 – May 17, 2020). In this conversation, the curators Beverly Adams and Natalia Majluf discuss the origin and the curatorial methodology of the exhibition and reflect on what it means to rethink the twenties through an editorial project that tried to lay the foundations for an Americanist and Indigenist avant-garde. Two ideological currents that are an antecedent of the decolonial thought of the region and that should be carefully reviewed in relation to the geopolitical reconfigurations of the present.

Florencia Portocarrero: I would like to start by asking you, how did the idea of curating an exhibition around the Amauta magazine arise and what have been the working hypotheses that have guided the project?

Natalia Majluf: It’s been a while since Beverly and I wanted to start an exhibition project around the 1920s in Latin America, whose historical recounts we felt were incomplete. One fine day, José Carlos Mariátegui Ezeta invited us to his grandfather’s archive, which houses important documentation from Amauta magazine. It is a very important resource, which is now accessible through the internet. [3] It was precisely in this visit to the archive that we decided to take the magazine as a starting point for the exhibition. This decision has been key, because Amauta allows to draw the twenties –politically, socially, and culturally– from the perspective of a privileged person like Mariátegui, who drew his own map of the region.

Amauta was not only focused on the modernization of Peru, but aspired to become a means of discussion for the different movements of social transformation throughout the continent.

BEeverly Adams: Amauta was an editorial project that managed to establish a network of exchanges of global reach at a particularly interesting moment in Latin American history. By the same token, it allows an accurate approximation to the twenties, as opposed to approaches that impose arbitrary categories to the discussion of the period. How we understand the Latin American art of that crucial moment? Actually, it can be addressed in many ways. But to understand such heterogeneity, we prefer to start from a historically situated perspective like that of Amauta.

FP: During the 1920s a series of movements emerged that, with reformist and anti- oligarchic demands, sought the renewal of the national imaginaries of the different Latin American countries. In this context, avant-garde publications functioned as platforms where new national consciousnesses were represented and discussed. What controversies did Amauta introduce about Peruvian social reality and what new perspectives on the twenties in Latin America are activated when they are examined through the lens of the magazine?

NM: It was a particularly open-minded era that wove real, concrete and extremely active networks around what we could call generational programs; such as university reform, anti-imperialism and the reconsideration of the very idea of Latin America. In the specific case of Peru, this equation must be added to the effect of the exiled Apristas [4] of the regime of President Leguía, who settled in Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Havana, and Paris; cities from which they sent information and materials for Amauta.

Amauta was not only focused on the modernization of Peru, but aspired to become a means of discussion for the different movements of social transformation throughout the continent. The very name of the magazine was a matter of broad debate. The first option was Vanguardia I resolved to call it Amauta after seeing Sabogal’s proposal. That says everything: the name places the commitment to the indigenous at the center of the magazine’s program, starting with the first issue, which has the cover of Sabogal, with the face of the indigenous character and a fragment of the famous book by Luis E. Valcárcel, Tempestad en los Andes [5], as opening text.

From Amauta, Mariátegui actively promoted the idea of indigenismo [6] as one of the axes of the American artistic and political vanguard. This attempt to articulate a local program with the international political and cultural scene complicates the views of later critics such as Marta Traba, who identified Peru as an insulated region, and indigenismo as a movement outside the margins of the art of its time. The exchanges that took place in the pages of Amauta show that, during the 1920s, Peru was one of the countries with the greatest openness and international connection.

BA: Precisely this is one of the points that most interested me in the project. In the official records, the twenties in Latin America are essentially represented by a few countries: Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Peru appears in the historical narratives of art only since the late eighties. Even today, there are significant gaps in the histories of art in the region. In Latin America, we write our national histories, but the continental history is usually written from Europe or North America. Amauta is a project that allows us to subvert or even reverse this logic. The magazine raises issues such as indigenismo, which is very specific within the Peruvian reality, but can challenge the world. Therefore, part of the attraction of studying that decade through Amauta has been to think how Peru, and, specifically, indigenismo could be reinserted into a history of art to which they clearly belong, but from which they have been omitted.

FP: Listening to you makes me think that a counter-hegemonic intention traverses the exhibition. By this, I mean that there is an explicit intention to critically revise the Western or Eurocentric canon, to generate a narrative that expands the way in which the history of Latin American art has been read, and, as a consequence, to circulate new discourses and knowledge from the region. Could you go deeper into this point?

BA: I’ll tell you an anecdote. When Natalia and I were graduate students in Texas in 1993, we visited a large sample of Latin American art organized in the United States, no other than in the MoMA [7]. After touring the exhibition, we found that, among many other absences, there was not a single Peruvian artist. Since then, I have found it very problematic how selective stories about Latin America are told, based on what is similar or more comparable to some pre-existing narrative written from Europe or North America. Amauta has allowed us to reevaluate the period and outline it from an organic perspective of the region.

On the other hand, for us, it was important to revindicate the place of Mariátegui as a fundamental critic of the art of his time. In literature and studies of the left, much thought has been given to his contribution, to the point that it is impossible to cover the bibliography. On the contrary, his contribution to the visual arts has barely begun to be studied.

NM: I think we could say that Mariátegui was one of the critics of Latin American art that was closest to the avant-garde art of Latin America and Europe. From early on, he followed the debates around the international avant-gardes and, despite his conviction that art should have a social and political dimension, he maintained an open and diverse vi- sion, which defined his interest in proposals that led to the exploration of the artistic languages. At the same time, in Amauta he problematized the notion of the avant-garde tied to formal experimentation, as well as the idea that the local is always opposed to the cosmopolitan.

In the exhibition, we tried to map that time through the open but programmatic gaze of Mariátegui. Most of the works that are in the exhibition were reproduced or discussed in the magazine. We have included artists such as George Grosz, Alexander Archipenko, Gabriel Fernandez Ledesma, Laura Cueto, Emilio Pettoruti, Juan Devéscovi, José María Eguren, Tina Modotti, Juan Antonio Ballester Peña, Agustín Riganelli, among many others. There are also elements—archives, books, photographs, and others—that were not published, but that reached the editorial board of the magazine and are essential to understanding the Amauta networks. We were interested in having this material present in the exhibition so that the public could observe the culture of the magazine and how knowledge circulated at that time.

FP: As the general editor of Amauta, Mariátegui promoted long gatherings among his collaborators, which often ended up defining the con- tents of each issue, even at the expense of their own political priorities. It has been said that this methodology was fundamental for the magazine to remain a generational collective and plural enterprise. How did you represent or transfer this plurality of voices and perspectives to the curatorial script?

BA: There is no intention to impose a unified narrative, simply to show the enormous diversity of the discussions and cutting-edge networks that Amauta fostered. The magazines in that decade had quite an extraordinary scope. They not only served as platforms for the exchange of ideas but also as exhibition spaces. We wanted the debates that took place in the magazine, such as the discussions on the vanguard, anti-imperialism, revolutionary art, and regional unity, were represented in the show, but without falling into the illustration of the ideas. On the other hand, we wanted to avoid generating compartments. In that sense, the Mariátegui archive has been very important, since it has allowed us to analyze the foundations and networks of Amauta. Within the exhibition space, works of art, documents, and archival material are located at the same level, generating a more complex narrative.

NM: The exhibition brings together a series of works, objects and heterogeneous documents, which have been spatialized and put into conversation for the first time. All this from the perspective of Amauta, which, in turn, is a magazine that raised key questions about the art of the time. The exhibition has sections devoted to indigenismo and debates around art and politics, popular art and pedagogy, all focused on the possibility of an American avant-garde.

FP: Mariategui put the indigenous experience at the core of the national imaginary. This bet had several fronts: first, an aesthetic one in the indigenismo, second, an ideological one in a Marxist or Inca vernacular, and finally, a political one that materialized in the Partido Socialista Peruano. How important is Mariátegui’s intellectual and political project for the present decolonial thinking of the continent?

NM: Mariátegui is an important antecedent for the critical and decolonial thinking of the continent (although at that time there was no talk of the decolonial, the term in use was anti-imperialism, which has quite precise associations and implications). He imagined in the collectivist traditions of indigenous communities as a basis for developing a modern socialist movement. In a country where the indigenous majority lived—and still lives—in a situation of marginality, this approach constituted a radical and necessary commitment.

The magazine Amauta was one of the axes of a larger project, which also included the work of labor unions and politics. Amauta was the intellectual branch of reflection, and also of recovery or enhancement of local arts and traditions. Evidently, Mariátegui had many blind spots in his approach to the indigenous world. For example, it is often said that indigenismo was a representation project whose attempt at vindication did not have as protagonists the indigenous people themselves. That is an entirely valid criticism, which allows us to recognize the contradictions that are part of the indigenist program. There is no complete project or realized utopia, but it should not be for- gotten that Amauta put into circulation a series of debates and images that materialized a revolutionary social and political project. To that extent, its work represents a very significant contribution that prefigured and defined new possible futures.

Moquegua, Perú, 1894 – Lima, Perú, 1930.

After the death of Mariátegui the Partido Socialista Peruano (PSP) was transformed into the Partido Comunista Peruano [Peruvian Communist Party] (PCP).

You can visit the document at the following link: http://archivo.mariategui.org/.

Alianza Popular Revolucionaria Americana – Partido Aprista Peruano, a center-left Peruvian political party.

Tempestad en los Andes is a book written by the Peruvian historian and anthropologist Luis Valcárcel in 1927. In a messianic tone, the book announces the moment in which the Andean peoples will rescue their ancestral tradition and wisdom.

Indigenismo is an art, cultural and political movement originated in Latin America during the 1920s, focused on reclaiming the indigenous cultural traditions, and the questioning European mechanisms of discrimination and ethnocentrism.

Comments

There are no coments available.