06.11.2017

50 years after the Tropicália movement that reshaped the culture of Brazil, André Sztutman and Lucas Rehnman contextualize the movement and reflect on its impact to sketch out the tropicalist legacy today.

Tropicalia ou Panis et Circensis: disco de lanzamiento del movimiento Tropicalista, con Caetano Veloso, Gilberto Gil, Gal Costa, Nara Leao, Tom Zé, Os Mutanres, Capinam, Torquato Neto y Rogério Duprat (1968).

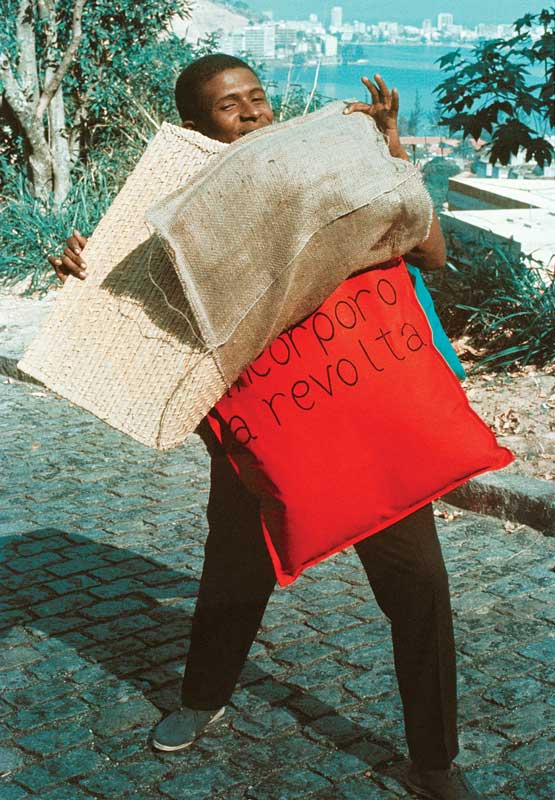

Nildo da Mangueira viste Parangolé P15 Capa 11 “Incorporo a Revolta” (1967) por Hélio Oiticia.

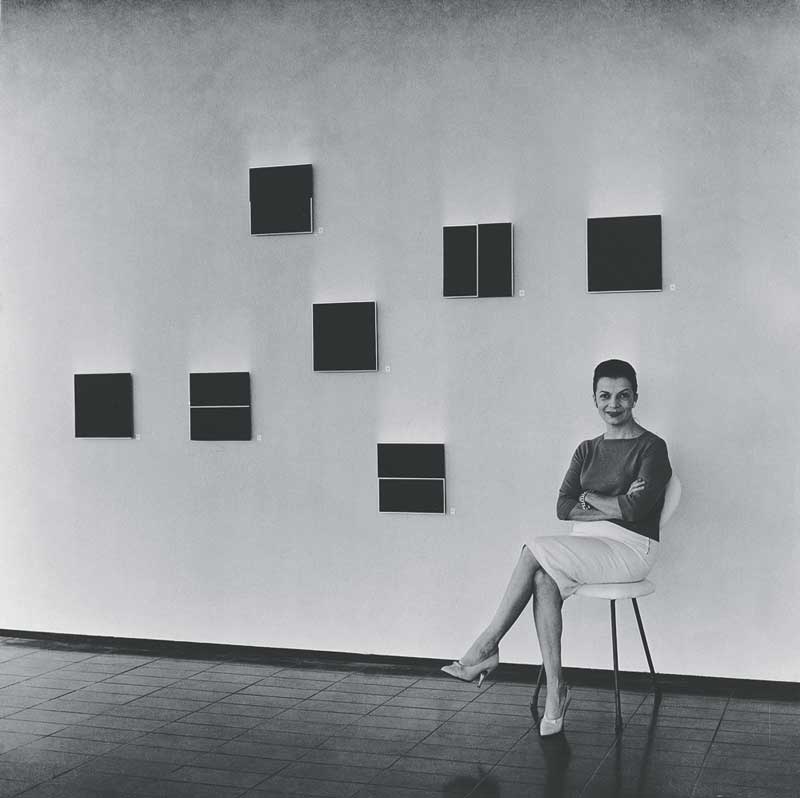

Ligia Clark.

Grabado de Theodore de Bry, 1592. Ilustración de el libro Verdadera Historia y Descripción de un País de Salvajes Desnudos de Hans Staden, soldado y marinero alemán.

Waly Salomao con rostro pintado por Helio Oiticica. Fotografía por Eduardo Viveiros de Castro.

Jorge Raka, Fall from the Flag, 2014. Video 01:12 min.

Dalton Paula, Implantar Amanú, video 10', 2016.

Tropicália, more than offering up an image of folklorized underdevelopment (as many wrongly interpret it), provides us with a creative space for de-colonizing poetics, bodies, and identities.

“Glauber ya preveía, ¿verdad? Que la Tierra temblaría en

“Glauber saw it coming, right? That the World would shudder in ’68. And it shook. […] All that cultural revolution in Brazil, back in ’67, that came before its worldwide, planetary manifesta- tion, that exploded in France, all over Europe, in China, Berkeley, everywhere. But the World shook first right here.” José Celso at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQjprQ-fRHU).

[Spanish-language translator’s notes: “hillside/asphalt” (morro/asfalto) is a popular way to speak of favela/city. Otário/ Malandro, in samba street poetics, are opposites. Otário is a pejorative way to speak of someone who lacks street smarts.

Music by Gilberto Gil and Wally Salomão. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PMoKBqy5HU4

From Cruz e Souza’s 1893 poem, “Tintas Marinhas.”

Even today in 2017, we’ve seen a small faction in society try to criminalize funk carioca, and dancing to it in favelas, in a reactionary and symptomatic desire to repeat the very worst of the past, another example of recent actions on the part of an exceedingly confused sector that has called for a new “military intervention” like the one in 1964.

José Miguel Wisnik lo apunta en O Minuto e o Milênio.

Canção Pra Niguém, music by Caetano Veloso (available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=icWyjPdyOmM).

Lorenzo Mammì, as published in Folha magazine (available at http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/ilustrissima/ il1007201107.htm)

Music by Baden Powell and Vinicius de Moraes.

Statement by Hélio Oiticica in O que faço é Música, a 1979 text.

Oswald de Andrade (1890-1954) was an important figure from Brazilian modernism. He was a poet, playwright, philosopher (see, for instance, 1950’s A Crise da Filosofia Messiânica), as well as the author of 1928’s seminal Manifesto Antropófago.

“I had just written ‘Tropicália’ when O Rei da Vela premiered. Seeing that play was a revelation to me that a movement was taking place in Brazil, a movement that went beyond the realm of popular music.” Caetano Veloso in his book Antropofagia.

“My experience as a marcher with the Mangueira is fundamental because I’ll always remember this: everyone creates their samba by improvising, in their own way and not following models; the people who do it by following models don’t know what samba is.” Hélio Oiticica in an interview with Mário Barata published in the Jornal do Commercio in 1967.

1959’s Manifesto Neoconcreto. Clark and Gullar invited Oiticica to join the group soon afterwards.

See Suely Rolnik’s psychoanalytic text, Lygia Clark y el hibri- do arte/clinica, (available at http://caosmose.net/suelyrolnik/ pdf/Artecli.pdf )

Hélio Oiticica, Aspiro ao grande labirinto (Rio de Janeiro: Rocco, 1986), 104-105.

Caetano Veloso, Antropofagia, 54.

Verses from “Divino Maravilhoso,” a song composed by Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil, performed by Gal Costa.

Arrangements by Rogério Duprat and concrete poetry’s in- fluence on tropicalista lyrics exemplified MPB’s erudite aspect.

Comments

There are no coments available.