21.11.2016

Fanny Drugeon looks at Dominique de Menil’s religious vocation and its impact on her collection.

For me, immersion in the Menil Collection, located in Houston, Texas, carried deep meaning. My years of research on the relations between abstraction and the spiritual finally led me to a face-to-face encounter with the Rothko Chapel.[1] Nor was this ecumenical chapel the whole of it. The 10,000 or so artworks and objects, from prehistory to our time and from across continents, gathered by John and Dominique de Menil from the 1940s until their respective deaths in 1973 and 1997, along with the opening of the Menil Collection in 1987, demonstrate the family’s engagement in connecting art and spirituality. In the collection, we circulate between epochs and geographic zones, from a Russian Saint George and the Dragon to Louise Nevelson’s 1959 Column for Dawn’s Wedding, from Yves Klein’s Monogold to the Altar Portrait of an Oba to the Edo people of Nigeria, from Cycladic sculpture to the Mayans to the Byzantine chapel, from Dan Flavin’s neon revelations, to Surrealist works with their ambiguous relation to different spiritualities. An invaluable trip through the storage rooms offers another approach, an immediate and not yet museographical look at the works, still shifting through time and space, from Oceania to Léger, from Brauner to Africa.

Words and works

At the inauguration of Houston’s Rothko Chapel in February 1971, Dominique de Menil mentioned the major role that her spiritual counselors Father Congar and Father Couturier played in her choices.[2] She had been profoundly moved by a series of reflections on ecumenism that Father Congar gave in a series of lectures in 1936, while she was still in France.[3] The desire to restore unity between Christians would lead, notably, to the creation of a World Council of Churches in 1948, after which Congar directed his research towards a more general aim of reforming the Church. This research eventually led to the Second Vatican Council. Father Couturier supported the renewal of sacred art in France, together with a group of people who had crossed paths with the de Menils; these included their friends Raïssa and Jacques Maritain, the Dominican Fathers Régamey, Laval, and Cocagnac, and the Abbé Morel.

In French, the idea of sacred art (l’art sacré) is ambivalent–close to both the idea of “religious art” and of “Christian art.” This fluidity is linked to a definition of the adjective “sacred” that is more open than restrictive. According to the Dictionnaire Le Petit Robert French dictionary, “sacré” refers to “what belongs to a separate, forbidden, and inviolable region (in contrast to the profane) and is the object of a sense of reverence,” but it is also, by extension, “what has to do with worship and liturgy.”On one hand, this definition of “sacré” can be linked to the idea of divine transcendence–a very open conception where art can be considered as sacred in its essence, independent of reference to any religion, which was the basis for de Menil’s approach–while on the other hand it is associated with devotion framed as dogma, or a strictly liturgical framework regulated by precise rules.

In it’s discussions of art, the Catholic Church promotes beauty first and foremost. The quality of form, judged by its own criteria, thus becomes a spiritual imperative. The definition used is essentially based on the ideas of St. Thomas of Aquinas, who defined the beautiful as what is pleasing to look at: “id quod visum pacet.” Hence “the new does not represent true progress unless it is at least as beautiful and good as the old.”[4] A whole line of thought formed within the Catholic Church around the question of the visual arts, starting primarily from Thomas of Aquinas’ three conditions needed for the beauty of an artwork to enrich the mind: integrity, proportion, and splendor. This idea of beauty and its sine qua non conditions were thoroughly rethought through the filter of Christian theology, and in this process became overtly moral, rather than purely aesthetic concepts. Traditional iconographic language, without being challenged or displaced, became the support for a theological language that by itself justified the Church’s use and acceptance of artworks. The educational/catechistic aspect of art was thus foregrounded.

In favor of sacred art

Beginning in the 1930s the de Menils financially supported the journal L’Art sacré (Sacred Art). This journal, created in 1935 and co-directed beginning in 1937 by Fathers Couturier and Régamey, fervently defended various contemporary trends in art before they were accepted in the churches, including the work of Fauvist and Expressionist Georges Rouault and of abstract painters.[5]

Dominique de Menil, who had converted to Catholicism in 1932, wrote for the journal three times in 1937, arguing for the importance of emotional reaction to art while discussing the painter Joseph Lacasse, and in another text, sharing her discovery of a Japanese church.

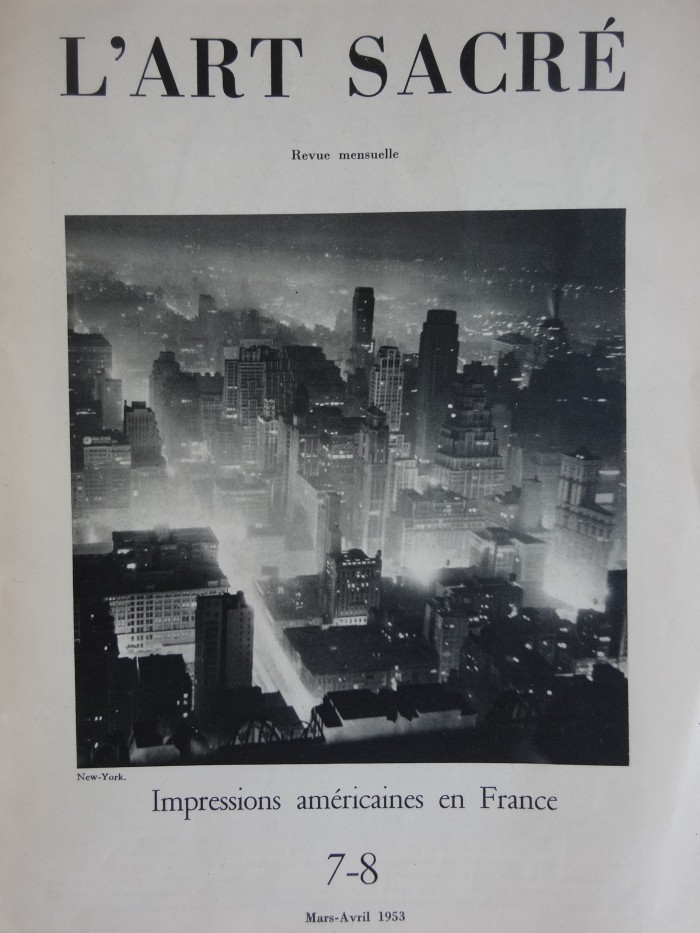

Almost 15 years later, the March/April 1953 issue paid tribute to her vision. In 1952, the de Menils had travelled through France with Father Couturier. This trip was very important to Dominique and led her to write the text “American Impressions in France.” Her account opens with a long praise of American architecture, and the confident grandeur of gesture in the Lever Brothers building, in stark contrast to the more timid French gesture. Her journey mixes heritage and the contemporary: the Abbey of Fontenay, stained glass of the Bréseux Church by the painter Alfred Manessier; the first abstract stained glass in France, just after the Second World War; Ledoux’s Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, which mixes “extreme rigor and extreme abandon”; and Van Gogh’s architectural series, Saint-Paul Asylum, Saint-Rémy. “Perhaps never since Byzantium have we seen a comparable sacred style,” wrote Dominique de Menil of the Sacré-Coeur d’Audincourt, a church in an industrial suburb built by Novarina and which includes works by Fernand Léger, Jean Bazaine, and Jean Le Moal.[6]

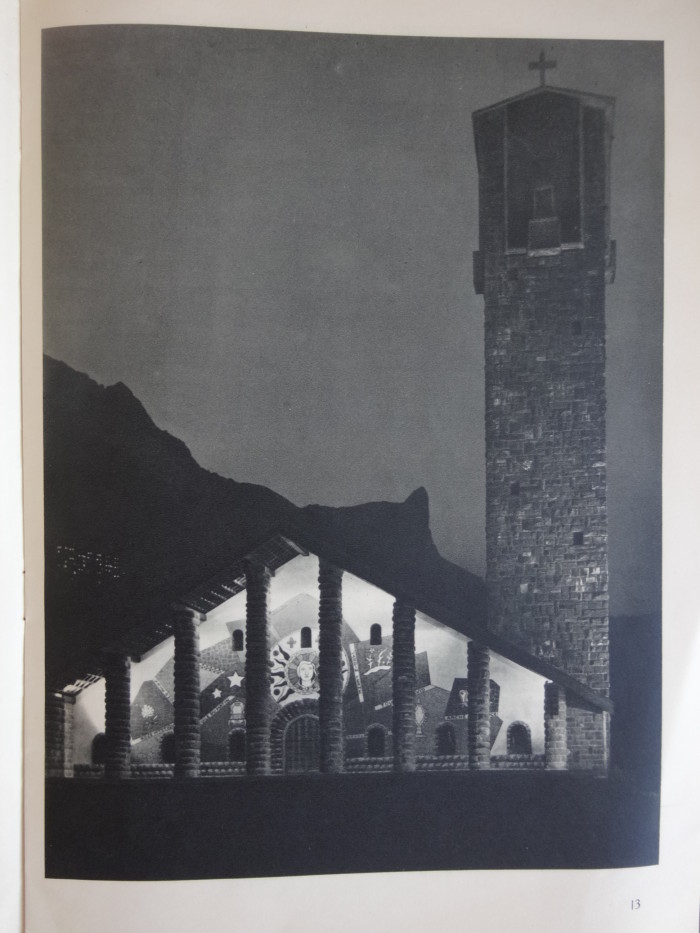

She focused particularly on Léger’s stained-glass windows, stressing their spiritual potential; “Through pure material intuition, Léger’s work meets with the language of mystics: the Crown of Thorns, the five Wounds, the Tunic.” And it is Léger again who provides the introduction to her arrival at Assy: “It is no slight to Léger to say that I find here the charm and poetry I found, between the ages of four and twelve, in Russian dolls, painted chests, and Nativity figures.” The de Menils had been following the evolution of Assy for some time, given that the artistic program for the Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce Church on the plateau of Assy (Savoie) was designed by Father Couturier and Canon Devémy in the 1930s. Completed after the war, the church was central to the “dispute” over sacred art in 1951. Germaine Richier, Rouault, Léger, Bonnard, Matisse, Braque, Chagall, Jean Lurçat. All were artists who the de Menils were happy to discover again, and who they admired despite the critics,: “What does is matter if not everything is perfect! The child is there; it will grow.” Shortly after, Dominique de Menil introduced Father Régamey to William S. Rubin, “a nice boy who has a sense for painting,”[7] who would study the church of Assy for his doctoral thesis.[8]

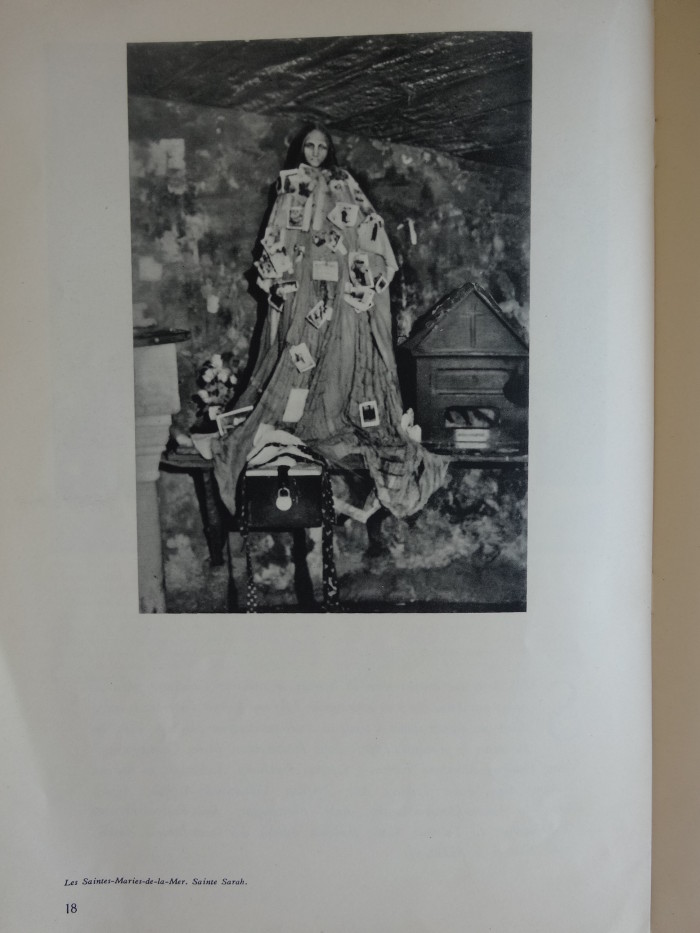

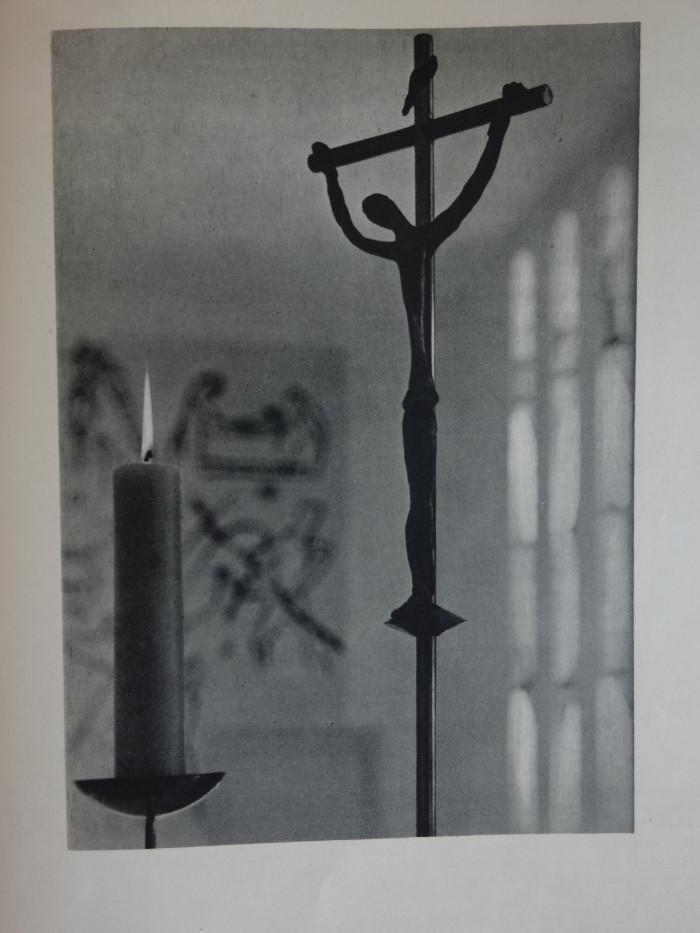

The de Menils’ visit to Saintes-Maries de la Mer and their openness to a range of artistic styles shown by the family’s interest in the sculpture of Sara, the patron saint of Romani people, demonstrate the curiosity we find in the Menil Collection. This curiosity also led them to send by mail various references to the Dominican monks, including, in 1959, a photograph Jean de Menil took of a Calvary pieced together by a Venezuelan mechanic: “It is made of an old car tire and pieces of tubing: the waste of the petroleum industry. There is often a bouquet of flowers in the center . . . despite the poverty of the materials that could be found in the scrap market, the cross impresses you with its nobility.”[9]

“Extraordinary Companionship”[10]

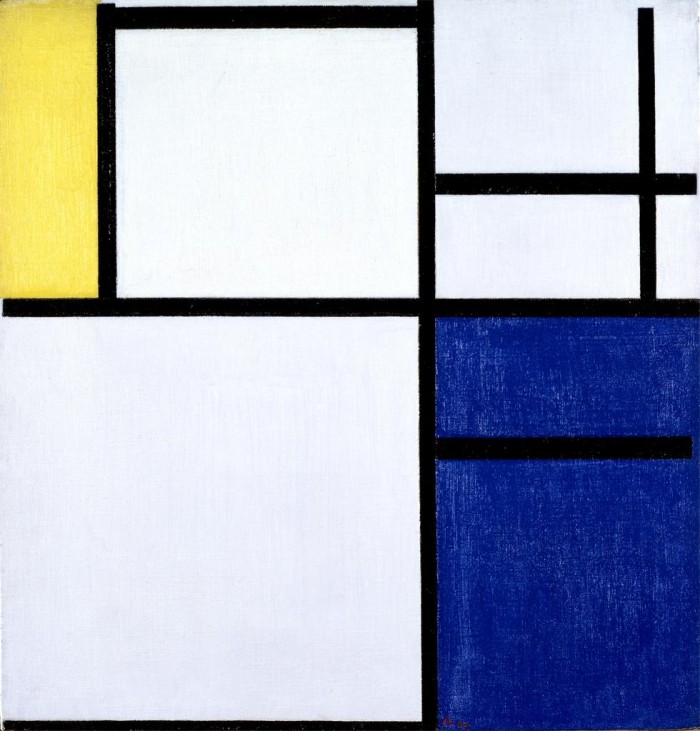

A notable issue of L’Art sacré opens with a view of New York and a photo of the house Philip Johnson built in Houston, and it closes with Matisse’s Christ in Vence and a view of the Cité Radieuse in Marseille, both in France. This variety gives a glimpse of the de Menils’ open spirit, which can be felt in the Menil Collection. Dominique de Menil wrote of Vence, that, “for one who knows how to see, it is an open book”; of Le Corbusier she said that he was “a man of vision.”[11] Action and time for contemplation were essential, and education equally so, as the family demonstrated by their support of the University of St Thomas. Both John and Dominique de Menil saw Father Couturier as an important influence in the evolution of their views starting from their first purchase of a Cézanne watercolor in the 1940s. For instance, John de Menil described his reaction when the Dominican Father first showed him Mondrian’s work: “‘Oh, Father, no, this is really going too far,’ and each time we couldn’t accept something, well we finally got to appreciate Mondrian.”[12] In this case, seeing the Composition with Yellow, Blue and Blue-White from 1922 evokes a sense of delight and discovery. Dominique de Menil also stressed Father Couturier’s importance, as he also helped her get over her feelings of bad conscience as a collector, an effect of her Protestant upbringing. She helped to publish Couturier’s writings and to continue his work, for instance through her involvement in the project at Ronchamp with Le Corbusier. Reading his writings after his death in 1954, she was enthusiastic: “I am astonished: the intellectual honesty, the vigor of his thinking, the courage, and finally the form are all marks of a master whose voice I am sure we are only beginning to hear.”[13]

These reflections punctuated my far too brief visit to the Menil Collection. I thought once again of Rothko and his quest: “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions–tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on–and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures show that I communicate those basic human emotions . . . The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them. And if you, as you say, are moved only by their color relationships, then you miss the point!”[14] There is a comparable mysticism in an artist like Ad Reinhardt, also included in the Menil Collection. We can see the link between art and mysticism in the letters he wrote to his friend, the Trappist monk Thomas Merton. For these artists, paintings–here abstract paintings–are not simple decorations or aesthetic distractions. They are born from meditation and can also lead to it. In a letter from July 3rd, 1956, Merton asked Reinhardt for “some small black and blue cross painting” he could hang on the wall of his cell in the Abbey of Gethsemani, in Kentucky, as an aide to meditation.[15]

To end, why not give Dominique de Menil the last word, one of her fundamental beliefs: “There is geographical kinship; and similarly there is spiritual kinship.”[16]

Notes:

[1] AUTHOR NAME (will be author of this text) Incarnation sans figures. L’abstraction et L’Église catholique en France, 1945-1965 [Incarnation without Figure: Abstraction and the Catholic Church in France 1945-1965] (PhD diss., Université François-Rabelais de Tours, 2007) has resulted in several publications. See for instance “Les abstraits et l’Église catholique en France après la guerre”[Abstraction and the Catholic Church in Postwar France] in Éric de Chassey, Ed., La Pesanteur et la Grâce. Paris: Collège des Bernardins / Rome: Villa Médicis, 2010, pp. 106-110.

[2] “Address in the Rothko Chapel,” February 26, 1971. Cited in Pamela G. Smart, Sacred Modern: Faith, Acti[3]vism, and Aesthetics in the Menil Collection. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2010, pp. 21-22.

[3] Yves Congar, Chrétiens désunis. Essai d’un œcuménisme catholique. Paris: Cerf, 1937.

[4] Address at the inauguration of the Pinacoteca Vaticana, October 27, 1932. La liturgie, vol. 1, ed. by the monks of Solesmes, Tournai, Desclée. Series: “Les enseignements pontificaux,” 1961, p. 260. For France, cf. I. Saint-Martin, Art chrétien, art sacré: regards du catholicisme sur l’art, France, XIXe-XXe siècle, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2014.

[5] For the journal L’Art sacré, see Françoise Caussé, La Revue «L’Art sacré»: le débat en France sur l’art et la religion (1945-1954). Paris: Cerf, 2010.

[6] All quotations are from “Impressions américaines en France,” L’Art sacré, March/April 1953.

[7] Paris: Saulchoir Library, Régamey archives.

[8] The future director of the painting and sculpture department at MoMA New York, then teaching at Sarah Lawrence College, spent a year in France after the war, and later carried out research between 1956 and 1958. His thesis, under the direction of Meyer Shapiro, was defended at Columbia University in 1959, and published as Modern Sacred Art and the Church of Assy. New York / London: Columbia University Press, 1961.

[9] Letter by Dominique de Menil, March 7, 1959. Paris: Saulchoir Library, archives of L’Art sacré.

[10] John de Menil used this phrase in reference to the works in his collection. “The Delight and Dilemma of Collecting,” lecture given at the University of St. Thomas, April 9, 1964. Menil archives: cited in Josef Helfenstein and Laureen Schipsi, Eds., Art and Activism: Projects of John and Domenique de Menil. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010, p. 120.

[11] In the foreword of La chapelle de Vence. Journal d’une création (Cerf/Menil Foundation, 1993), Dominique de Menil insists on the “spiritual relationship” between Vence and Rothko Chapel.

[12] Josef Helfenstein and Laureen Schipsi (ed.), op.cit., p 121, p. 121.

[13] February 16, 1962. Paris: Saulchoir Library, archives of L’Art sacré.

[14] Selden Rodman, Conversations with Artists. New York: Devin-Adair Co., 1957, pp. 93-94.

[15] “Five unpublished letters from Ad Reinhardt to Thomas Merton and two in return,” Artforum 699, December 1978, p. 23.

[16] Dominique de Menil, “Impressions américaines en France,” op. cit., p. 15.

Comments

There are no coments available.