02.07.2018

Haitian curator Giscard Bouchotte questions the ideal of freedom inherited from the Haitian Revolution through the work of Ishola Akpo, Josué Azor, Maksaens Denis, and Nicola Lo Calzo.

Revolution and Creation

This text explains how the world’s first Black republic has renounced the dream of fundamental freedom that the heroes of its independence—of whom the nation today claims to be the fervent heir—proclaimed by denying basic human rights to the majority of its citizens. Fortunately, some Haitian artists use their artistic agency to make visible the religious and sexual minorities that conservative forces have preferred to ignore.

The Price of the Revolution

On January 1, 1804, the French colony of Saint-Domingue became Haiti. Slavery, already illegal in France, had been tolerated in the overseas territories under the pretext of a state of exception. Official history recognizes the “Pearl of the West Indies” as the First Black Republic of the world, but obscures the gray areas of the revolution and the price that had to be paid. Twenty years after independence, King Charles X of France agreed to recognize the new republic in exchange for 150 million gold francs, subsequently reduced to 90 million—a colossal amount that the young republic had to pay over a period of forty years—to compensate the French settlers who had been expelled from the island. [1] It was not until 2003, when the Haitian government introduced a claim for official reparation, suing the French government for a sum of twenty-one billion dollars, that the whole world discovered the scandal. This class action is in line with other ongoing similar cases, including that of Black Americans demanding compensation for the violence inflicted upon their ancestors and for the consequences of the slave trade on their current situation in American society.

Haiti’s independence is entangled in its own paradox: although the revolution freed a whole people from the colonial yoke, the new republic remained economically dependent on its former master, the ups and downs of which are unavoidably visible in the archive of the reparation. The ensuing political isolation, the various dictatorships, the economic embargoes, and the different occupations [2] pushed away, little by little, the dream of freedom for all as the Haitian revolutionaries had imagined it. Today, the méringues [3] of carnival evoke the resistance of ancestors; even now, more than two hundred years after the revolution, the people continue to identify with these heroes of Haitian independence for the country lacks any contemporary figures capable of embodying popular aspirations. In the commune of Croix-des-Bouquets, as Nicola Lo Calzo’s [4] photographic series Cham testifies, some young people travel the country’s cities, putting on performances about Jean-Jacques Dessalines [5] and other main heroes of the revolution through their association “Movement for the Success of the Image of the Heroes of Independence.” This group’s self-proclaimed mission is “to teach the new generations, precarious and uneducated, about the glorious history of the Haitian Revolution through historical re-enactments.”

These attempts to connect with the heroes of the nation offer the popular imagination an opportunity to stand in resistance against the privileges granted to those who govern. In 2013, the Kita Nago movement—a caravan of hundreds of thousands of people carrying the trunk of the Tree of Freedom [6]—arrived on the post-earthquake scene, when the majority of the population found themselves without home or transport. The movement called for an alternative model for the reconstruction of Haiti, one that took into account the needs of the majority of citizens.

The work of Nicola Lo Calzo illustrates this attachment to the cause of the heroes of the past, as well as shows us how collective memory resides in colonial heritage and individually feeds this obsession with the past. Today, some plantations that were formerly sites of national defense or simple witnesses to colonial power have become popular pilgrimage sites for followers of voodoo [7], sometimes numbering in the thousands, as occurs at Bassin Saint-Jacques in the north of the country. As important as they are for believers, these pilgrimages do not take in account the thorny question of the destruction they inflict on these heritage sites as a result of the number of visitors and the wear of time. And indeed, to this day no voodoo authority has been officially recognized in Haiti, and, in any case, they would not have the means to maintain the sites. Some of the more frequently visited of these lakou’s [8] have been entrusted to the Ministry of Tourism or the ISPAN (Institute for the Conservation of National Heritage), but the resources allocated to this institution are scarce compared to the task at hand.

Fundamental Freedoms in Haiti

We cannot mention the fight for fundamental freedoms without mentioning liberation theology, whose proponents Jean Bertrand Aristide and Jean-Marie Vincent have been the most eminent figures in Haiti. Like prophets, they were charismatic figures, who preached what is good for the people, in the name of God. But, according to Max Dominique [9], liberation theology failed to profoundly transform the social reality of Haiti because of the complicated context and the impossibility of morphing theory into a real “politics” of liberation. Nevertheless, liberation theology allowed people to participate in the long run in the democratic transition of the country.

From the Haitian Revolution, one can recall the ideal of freedom for all (and not only for white men, as the French Revolution of 1789 had proclaimed [10]), a founding element of any democratic society today. Still today, fundamental freedoms are at the heart of global societal debates, and constitute the pillars for the emancipation of peoples. However, more than 200 years later, even those who claim the legacy of the heroes of independence do not always take the measure of the revolutionary ideal. Reporters Without Borders’ 2018 World Press Freedom Index [11] places Haiti at fifty-three, revealing the intensity of state aggression towards journalists and pinpointing how certain ideologies and private interests hinder the freedom and independence of journalism. Closely linked to freedom of the press, the barometer of individual freedom often sums itself up in Haitian society’s intolerance of religious and sexual minorities and women, as well as the place they grant these groups.

Many foresaw a civic awakening in Haiti following 2010 earthquake. It didn’t happen. At the same time that Ishola Akpo’s photographic series (Im)possible [12], which questioned the future of the majority and its impossible dreams, came out, a series of ideological and religious discourses started to appear, supported by extremists who declared that the earthquake was a manifestation of God’s wrath against practitioners of voodoo and sexual debauchery. These extreme statements, affiliated with the growing Protestant community in Haiti largely imported from the United States, find their legitimacy in the logic of scapegoating and in the systematic opposition to voodoo. For several months, no voodoo ceremony was possible in the country, especially in the affected areas. Then began a manhunt that was reminiscent of a different time in the country’s religious history when followers of voodoo had to hide in order to practice their faith.

This climate of intolerance linked to the explosion of Protestantism in the country is a threat to fundamental freedoms. The ostentatious invisibility of women [13] in certain trades and key positions of power and the repeated threats against the LGBT community in the public sphere in Haiti are all evidence that there is still some pedagogical work to be done regarding fundamental freedoms. In September 2016, when the Massi-Madi Festival was announced, it triggered so many protests across several sectors of activities that the organizers had to give up their dream of an LGBT festival. Yet individual freedom is guaranteed by the State’s constitution. Weren’t free debate and the right to difference part of the Haitian revolutionary ideal?

The Power of Creation

Freedom of expression is mentioned in the Haitian Constitution of 1987 and is defined in Article 28, thanks to the large number of authors who work across all manner of social media in Haiti and who have important voting power in Haitian society. Artists are then better positioned to raise awareness in the government about the emancipatory dimension of creation in order to demand the autonomy of bodies and sexualities, reminding them of the supreme values of tolerance and open-mindedness. Artists are able to redefine norms and open the field of possibility accordingly.

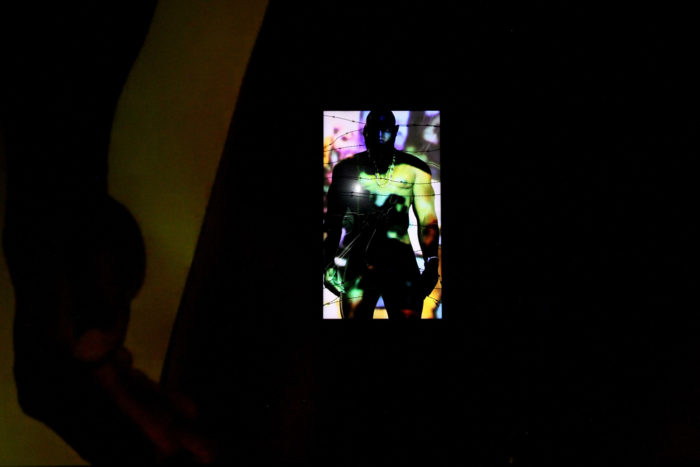

The photographer Josué Azor is one of the few Haitian artists to address the issue of the living conditions of minority communities such as voodooists and LGBT people. [14] His series Nocturnes testifies to the vitality of these communities of invisible men and women—those who have never been officially registered. Similarly, the work of Maksaens Denis, with his series Tragédies Tropicales [15], disrupts the imaginary of social goodness by discreetly integrating the male nude in his video installations. They are not the only ones, but in their work as observers of society they question their spectators and ask them to open their eyes to the world as it is, and not as we wish to see it.

Every national narrative values a certain number of heroes whose ideals are brandished for the benefit of those who use them. It is valid to wish to “die for the homeland” [16] and to sanctify the colors of the national flag, but it is necessary for us to liberate ourselves from certain obsolete slogans in order to rewrite a new national narrative: a story that reminds us that love for the homeland is the love of all of those with whom we share a common destiny and a common land. The democracy we desire cannot get rid of the ideal of freedom enshrined in Haiti’s Act of Independence, for this act is the formal expression of a conception of freedom that is full and complete. In 2018, those who wish to honor the revolutionary ideal shall call for more tolerance, constructive dialogue, and the abolition of the privileges of the few in order to improve the lives not only of a part of the people, but of all the citizens of this country.

—

[1] “Haïti et la «dette de l’indépendance»,” Le Monde diplomatique, August 7, 2010. Consulted on May 21, 2018: https://www.mondediplomatique.fr/carnet/2010-08-17-Haiti

[2] Max U. Duvivier, Trois études sur l’occupation américaine d’Haïti 1915-1934 [Three studies about the American occupation in Haiti, 1915-1934] (Canada: Mémoire d’encrier, 2015).

[3] Méringue is a Haitian dance that was influenced by both the contradanse of French colonists and Afro-Caribbean dances from Hispaniola. The dances in carnaval have become a mode of cultural and popular catharsis and often address contemporary and historical problems in Haiti.

[4] Nicola Lo Calzo’s Cham can be found at http://www.nicolalocalzo.com/fr/cham/view/7/ayiti

[5] Jean-Jacques Dessalines was a leader of the Haitian Revolution and the first leader of Haiti.

[6] Toussaint Louverture (1743-1803): “By overthrowing me, they have only cut down the trunk of the tree of freedom of black people; but it will grow again from its roots, because they are deep and numerous”.

[7] Jacques de Cauna, Patrimoine et mémoire de l’esclavage en Haïti: les vestiges de la société d’habitation coloniale [Patrimony and Memory of Slavery in Haiti: The Remains of Colonial Plantation Society], In Situ: Revue des patrimonies 13 (2013). Consulted on May 21, 2018: http://insitu.revues.org/10107

[8] In Haiti, a lakou is a small village or complex built around a shared patio, or the family structure of those who live in these places.

[9] Max Dominique, Rôle de la théologie de la libération dans la transition démocratique en Haïti [Role of Liberation Theology in the Democratic Transition in Haiti], ed. Michel Rency Inson (Paris: Les Éditions Syros, 1995), 63.

[10] Régis Debray, Haïti et la France, Rapport au Ministre des affaires étrangères (Haiti and France, Report to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs), 2004. Consulted on May 21, 2018: https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/rapport_haiti.pdf

[11] Reporters Without Borders, https://rsf.org/fr/classement

[12] (Im)possible is a series of photographs representing anonymous passerbys in the city of Port-au Prince with dreams in their eyes.

[13] Invisibilité ostentatoire (Ostentatious Invisibility) is also the title of an exhibition curated by Giscard Bouchotte, the author of this essay, at Fondation Clément (Martinique, 2017): http://www.fondation-clement.org/Decouvrir-les-expositions/In-visibilite-Ostentatoire-Exposition-collective

[14] David Frohnapfel, “Photographing Queer Life in Port-au-Prince”, Hyperallergic, June 25, 2015. Consulted on May 21, 2018: https://hyperallergic.com/217688/photographing-queer-life-in-port-au-prince/

[15] See Maksaens Denis’s work at https://www.maksaens-denis.com/

[16] See the Haiti’s national anthem, La Dessalinienn

Comments

There are no coments available.