Issue 14: Look Who's Talking - Estados Unidos

Demian DinéYazhi’, Alan Peláez López, Diego del Valle Ríos

Reading time: 13 minutes

27.05.2019

Diego del Valle Ríos, editor of Terremoto, talks with Alan Pelaez and Demian DinéYazhi’ about the personal and collective implications of confronting the colonial state, white supremacy, and heteropatriarchy in the US.

The coloniality of seeing can be described as cognitive and semantic devices that trace the evolution of social imaginaries in favor of a capitalist hegemony that is essentially racist. This is how the gaze conditions our possibilities of being together: everything that capitalism indicates us to see, and thereby feel or understand, is due to a strategy that reinforces it.

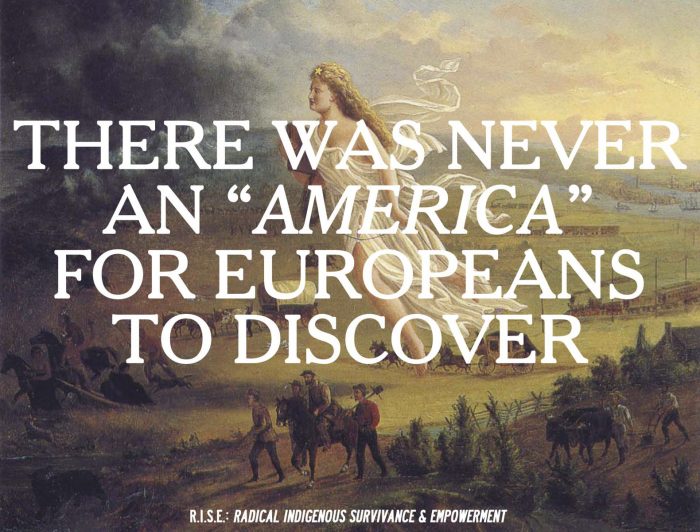

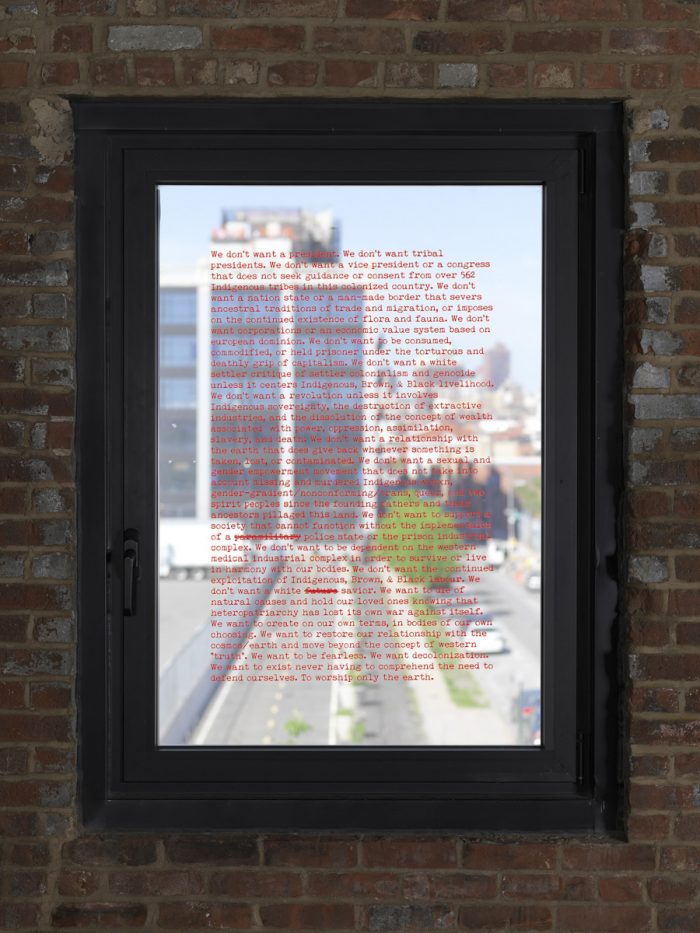

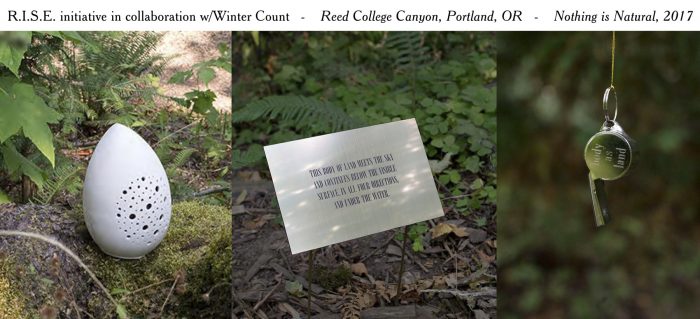

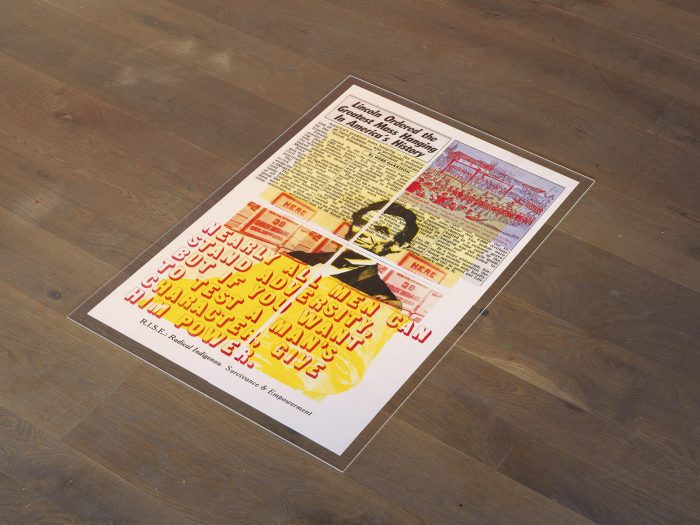

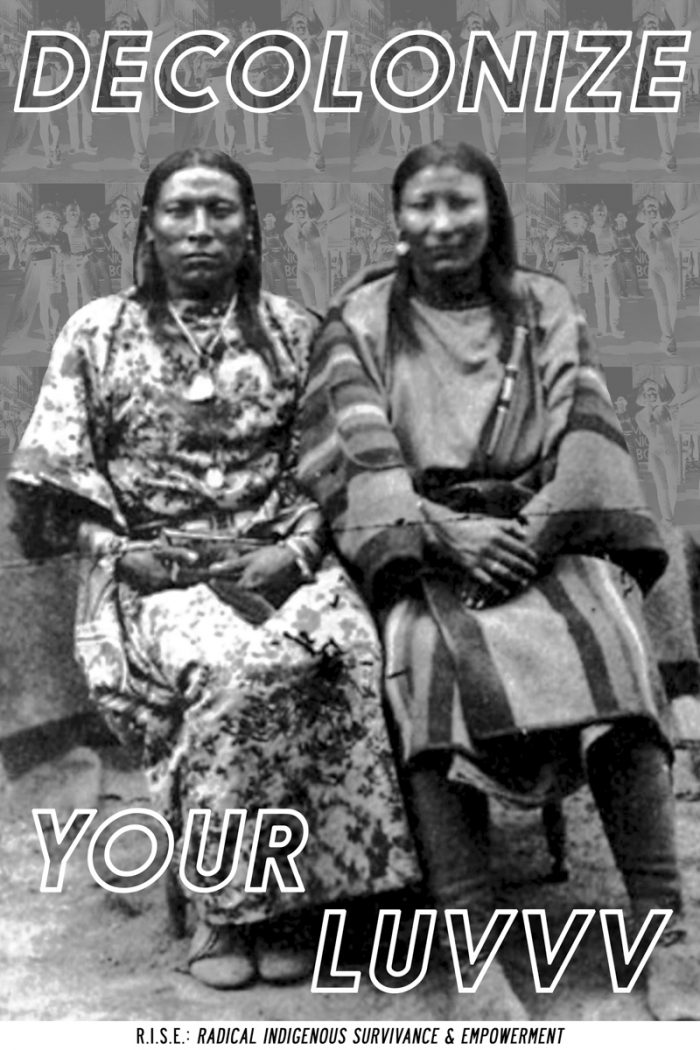

To reflect on the possibilities of resistance and emancipation of this unconscious force, I spoke with Alan Pelaez and Demian DinéYazhi’. Alan is a poet, writer, and artist who evokes through their writing a diaspora present not only in their personal history but also in the affectivity of their social circles, in relation to be Black, Queer, Latinx, and Indigenous. Similarly, the artist/activist initiative, R.I.S.E. (Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment) founded by Demian, makes use of word’s graphic visuality to place it into tension in juxtaposition to images, and thus, form slogans of resistance that exhort unity and solidarity among the descendants and members of the Native American tribes.

Diego Del Valle Ríos: Your practices are a node that, from the incarnated word—which is the distillation of your ancestors’ experiences and knowledge—gathers the shared resistance and struggle between bodies that have been cornered and violated by homogenizing discourses and its representations. Both of you are in a rejection of the colonial state, white supremacy, and hetero-patriarchy in the US. How is it that your artistic practice came to this rejection and what does each of these toxic axes mean to you?

My poetry, then, serves as a way to talk back to empire and reclaim my love, my mourning, and my damn right to celebrate all parts of me.

Alan Pelaez: My poetic practice stems from beading. As a young undocumented person, I began to bead at seven-years-old in order to purchase food. While food was the immediate reason, I took up beading as an unintentional spiritual practice because that’s how kin in my community tell stories and retain our culture. Beading alleviated my constant fear of living as an “illegal alien.” Once I learned to read and write in English (this took about six years), I started to explore written poetry. As a poet, a portion of my writing attempts to contextualize what it means to love and mourn in the age of displacement. Loving as a queer Black and Indigenous person is in itself a rejection of the colonial state, white supremacy, and heteropatriarchy. At the same time, my constant thinking of mourning has allowed me to realize that our (Black, Indigenous and Queer) bodies were never meant to constantly mourn. Instead, at least in the Zapotec community, our bodies were to be celebrated. My poetry, then, serves as a way to talk back to empire and reclaim my love, my mourning, and my damn right to celebrate all parts of me.

Demian DinéYazhi’: Like most indigenous and queer peoples, I feel my rejection and critical response to white supremacy came through years and years of self-destructive behavior. Until I reach a critical point of complete self-destruction, I began to analyze and figure out what the source was. For people who grew up in border-towns, it’s sometime really challenging and difficult to find a name or place amongst our community, specially when there are conservatism and assimilationist agendas that have completely misshaped peoples relationships to both the land and any social culture or landscape.

It was through confronting and recognizing the ways in which I was uncomfortable in white spaces that I began to eventually unpack my own ancestry. My self-destructive nature and tendencies as an indigenous queer person coupled with really embracing my ancestry in relationship to severe extreme white culture, really allowed me to understand myself as a result of being completely colonized by white ancestry—this suffocating and disgusting hetero-patriarchal forest that corrupts and corrodes communities. I grew up mostly in a matrilineal female household as part of a tribe with a matriarcal and matrilineal ancestrally. Having so much curiosity in women and gender studies, and being critical about how these are usually constructed and radicalized through European-White settler perspectives opened my eyes to the need to find my own voice and language.

By owning my voice I found other people having the same discussions and insecurities, asking similar questions, and feeling the same way. R.I.S.E is a response to that, it is not only my voice is a collective response—female and indigenous queers who are also part of feminist communities. It’s a loud decolonial politic to be asserted to settler colonialism, white supremacy, hetero-patriarchy capitalism, or any imposed form of Western construct.

DDVR: You both describe a process of personal reconciliation through which you are vindicate your experience away from the imposed colonial perspective that had a strong impact on your personal growth—in relation to your communities—by imposing stereotypes and circumstances of violence, precariousness, and abuse. How did you handle the uncertainty and complexity of recognizing yourselves vulnerable of white supremacy? How are you reclaiming art and poetry from a decolonial perspective within these processes?

AP: I think it is similar to how Demian spoke about self-destruction. For me there was a lot of self-destruction in my early childhood after I migrated to the US, where I found out that I was Black. I have never had that language back in my village in Oaxaca. My early life was about denying my own Blackness at the same time as I was denying my Indigeneity in the sense that I knew we were indigenous because of the amount of racism and classism we faced back in Mexico.

When I was 15 or 16 I began to realize how a colonial perspective, facilitated by white supremacy, was imposed on me in relation to how I was supposed to operate in the world. In the US I’m always recognized as Black before being recognized as Indigenous or Latinx. For me, it has been a really tough time to hold myself to both my Blackness and Indigeneity and never detach them: I’m a Black Zapotec person. I’m afrodescendant; both my parents are Black and Indigineous. Lack of visibility makes my community very vulnerable to the violence of white supremacy: the extermination of both the Black and Indigineous bodies—physically and in terms of representation—as well as the ongoing occupation we are facing in our village in Oaxaca.

Art and poetry allowed me to approach my fear of forgetting my life back in our village, especially after being undocumented for 17 years. Poetry is the way I activate all that memory and hold myself—and my worst—to find a process of reconciliation and find a language for my own experience. A lot of my family members who are still undocumented may not have the language. I’m finding a language—both in Spanish and English—in which to explain some of the things that I have lived to see if these are legible to them so they can potentially relate and put words to their own experiences. What my poetry, story-telling, and visual art does is find language when white supremacy is continuously trying to take it away from us.

DD: In its developmental stage, R.I.S.E. was uncertain about its ways to form itself and to function. This was very evident when opening first conversations with art institutions: I was missing an analysis of my own connection to language. My relationship with English— really the only language that I speak—was through a colonized and assimilated perspective. Initially, it was difficult for me to use terms like decolonial or survivence. I felt more comfortable using terms such as deconstructed, subversion, reclamation. Decolonial language and perspectives in Indigenous communities are missing a common language that each individual indigenous tribe could use to identify between each other on how they are coming up against white supremacist and settler colonial nationalism. I’m interested in finding this possible vocabulary within my tradition. A huge part of this means moving back home and having a relationship with it, spending time intentionally, relearning it.

The main effort of R.I.S.E. is to provide a space of representation for indigenous peoples. Sometime we fail; sometimes we are not the space for that. Assuming its complexity is a starting point. Today, due to anxiety, art, poetry, and politics evolve in such a rapid ray hindering the possibility to remain in one place for to long. To break this velocity, we need more exchange between younger and older generations, an inter-generational dialogue.

On the other hand, the work that R.I.S.E. has invested in, is mindful of the ways in which the socio-political landscapes are vastly different between reservation life and non-reservation life. Right now, I find myself in NY City, a Western colonized city that continually erases indigenous peoples. Yet, I know that the lived experience in a reservation (taking care of the land, crop, farm) is a very different knowledge system at play. A life experience to take in account. A lot of the languages we are using at R.I.S.E. are not accessible in reservation life. Here I start to question ways in which, not only R.I.S.E., but other community engage spaces invested in long term decolonial projects, can provide access and have this conversations. I don’t want to get too far away from my people and reach the point in which I take my work to the reservation and is not understandable.

DDVR: From what you describe, I inevitably thought about a phrase by Mario Pedrosa—an important figure of Latin American solidarity within the arts—: “art is an experimental exercise of freedom”. What you both described is art as a tool to create language that allows a personal understanding to create the possibility of a common vocabulary and grammar. Get to recognize your own experience from that emancipated new language allows you to feel comfortable, to create a share history in which you exist as someone with optimism allowing communality, solidarity. Can you tell us about the communities you’ve found through this common language?

I don’t think this world is a safe place for us to be angry, but anger is an important tool to reclaim ones liberty and find unity.

AP: I appreciate the way you contextualize the grammar that our art shapes, re-imagines and reclaims. The communities that my work has allowed me to connect with are indigenous peoples that were born in Latin American and the Caribbean, who are now living in the US. I personally struggled a lot with understanding what it means to be Indigenous and being immigrant. Through my art I meet a lot of community members, who are undocumented and Indigenous, who also struggle with the same questions: can Indigenity be claimed in the occupied states? What does it mean to be differently indigenous? Being undocumented is mainly an Indigenous experience, since we were displaced by violent settlement in an everyday level, forcing our communities to seek refuge somewhere else or to hide temporarily with the future intention of being able to go back home.

Hearing Demian, I would like to reflect on the ideal of how to provide access and how do we navigate space together. Primarily, because of conversations that I try to have with my mom about being indigenous in the US and what does that means. My mom, here in the US, before she is anything, she is an undocumented person who is continuously hiding from ICE, the police or any form of government. In our communities there is an absence of time to talk about these important questions. I hear Demian’s call for inter-generational dialogue, which is the only way to share our experiences and know those in other ongoing occupation settlements. Developing grammar books for all of this is difficult but necessary.

The second community I’ve been taping into through Twitter and Instagram, are other queer, trans and Black folks. We look for each other to make sure we are ok. Is a kinship unit that has been formed out of a need to continue to give each other optimism on the midst of catastrophic violence. Here I want to stop in the work that Demian does, which has provided a perspective I didn’t knew I needed, a form of engaging in deep reflection on how others impact the way in which I’m able to have a relationship with myself, the land and community who may claim or may not claim me back.

DDVR: Let’s focus on what we share and how we impact each other. Being Latin America a territory invented through colonialism, how do you envision a possibility of solidarity departing from the colonial wound we share? How can we be together beyond the limits of identity politics’ subject rhetoric? Sometimes I feel that perpetuating ourselves as a resistance—whether Indigenous, Queer, Black, Latinx, Feminist, Trans*—keeps us paralyzed in a rage that is always waiting to react to violence.

DD: Some of us are born angry. When I talk about self-destructive tendencies, I think those come out of an anger that wrestles inside my ancestors and myself. But I was also born into the world crying and I learned how to laugh. I didn’t learn how to laugh on my own, somebody had to cause it. I don’t think this world is a safe place for us to be angry, but anger is an important tool to reclaim ones liberty and find unity: a community of other survivors who have experienced the same anger, devastation, frustration, and spiritual turmoil. Anger can be a useful tool when it’s not following self-destructive behaviors. As long as this nation-state survives in this false illusion of democracy and freedom; as long as Indigenous people do not have rights to their own resources, their own language and ceremonial values; as long as there is a disgusting and corrupt border that separates the natural world and human’s desires and ability to migrate and exchange knowledges, it’s necessary for us to resist, for us to have this conversations and work through our anger and frustration in ways that are not perpetuating white anger tendencies, often tied up to violence, death, and terrorism. To resist through love, optimism, and the desire to be the most fulfilled version of us that we could ever possible imagine.

AP: There is something really powerful when our bodies engage and respond to emotions. Particularly, as colonized subjects, when we feel and when we name those feelings, we are directly speaking to the structures of empire and settlement. Rage is definitely a way to speak back, to fight back and to reiterate my comrades. As long as we are not perpetuating white nationalist anger, rage is an incredible tool. I have learned this rage from my elders, my own spirit and from young people around me who, when they realize that something is wrong, they listen to their anger, a feeling I wasn’t allowed to feel when young.

One of the ways to be together is to figure out what it means for each individual of us to be a better relative to one another. Recently, I was hearing Lee Rayfort talk about the violence that Black women experience. At one point, she said, “sometimes I have to remember that although I am a Black woman, I’m sometimes not the most oppressed person in that space at that exact moment.” I’ve been thinking around this, especially as we navigate different intersections and the way in which we all have experiences of oppression. What it means to be a better relative in these times? Having a relation to our emotions is a place to start, because our bodies know when something is not right, when something is inherently causing us, or our communities, violence. Another aspect on this is to speak our emotions out loud, normalize conversations around anger, joy, mourning, depression, love… To develop a grammar of how we feel, why we feel, when we recognize that feeling, and what that feeling has activated in us. I don’t think anger is a negative thing at all, emotions like that are tools that coloniality has tried to fool us into believing that we can’t have a right to. Feelings are a critical knowledge for the future.

Comments

There are no coments available.