26.08.2019

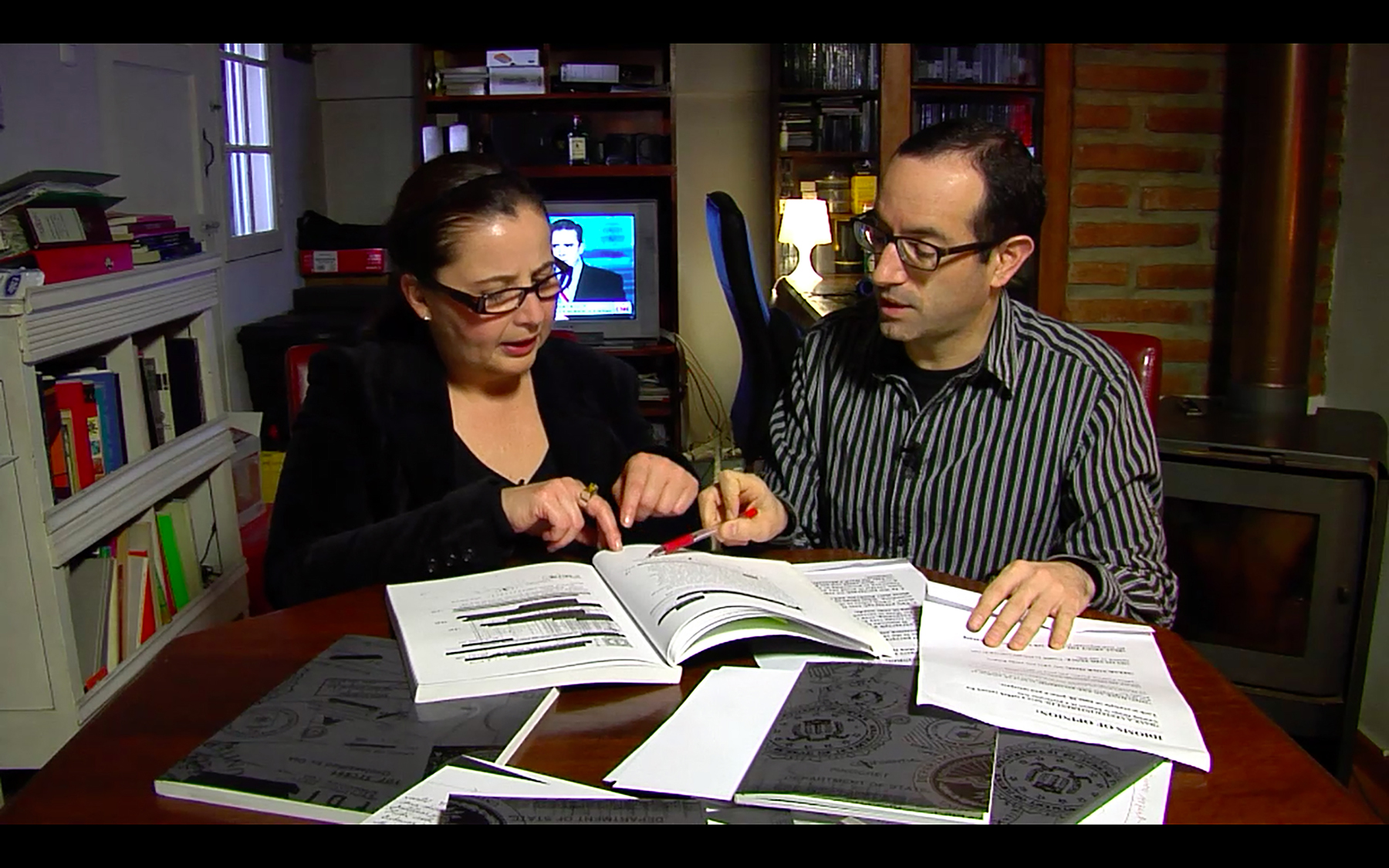

Curator Sofía Carrillo reflects on the archive and the document from territories of displacement, «occurrence», and the politics of the activation of memory derived from approaches discussed in the conference «Archivos fuera de lugar» [Displaced archives].

First Notes for a Proposal for the Decolonization of the Archive

The document allows us to evoke, discuss, and delineate that which wished to be obliterated; to remember the forgotten.

In The Archive and the Repertoire, [7] Diana Taylor begins by explaining the importance of performance as a medium for transference, in which the contextual information and knowledge of a society are maintained by virtue of repetition. What is interesting about her analysis is the moment she rejects the authoritative field of the archive as the means of safeguarding this type of memory and discourse that can only exist in terms of presence and action. The repertoire would then be the catalog of a body which takes the place of the arkheion. Here, historiography makes no sense; the rules of the body and its referents, affective, contextual, and in a constant state of construction-interpretation, are the territory in which linear temporality is replaced by reiteration, putting into play all times in one.

When I refer to the archival “boom,” or the archival turn, it is necessary to understand the complex structure of the art system that today responds with policies of acquisition and donation, putting into circulation a narrative about artistic praxis by means of the document as it is seen in exhibitions and through the construction of historiographical discourses, the revalidation of the artist in the medium, and the materialization of ephemeral pieces that now form part of public and private art collections; in short, the consideration of the document and the archive as cultural and economic assets that redefine their function in the cultural field. Due to this phenomenon, a privatizing trend can be observed with regards to the document in the market and even a return to the privatization of discourses of the historiography of art⎯a situation that seems even more dangerous to me; however, the leakage of these materials into collective methodological fields, plural readings, cross-sectional reviews, word mobility, among others, is an example of a decolonial seed in the archive.

The Proyecto Juan Acha [Juan Acha Project] houses the library and archive of Juan Acha, a Peruvian-Mexican theorist and cultural agent who transformed art criticism and theory in the 1970s in Mexico and much of Latin America. This archive was donated to UNAM in 2008 and is currently in the process of relocating within the Centro Cultural Universitario Tlatelolco [Tlatelolco University Cultural Center]. It is open for appointments. Furthermore, it involves a critical review of Acha’s legacy with respect to his ideas about restructuring the art system based on the idea of the art object as cultural object. The team is made up of Mahia Biblos, María Elena Blanco, and Joaquín Barriendos.

See Gilles Deleuze, Lógica del Sentido. (Barcelona: Paidós, 2005), p. 183.

Rita Eder, “El arte No-Objetual en México” in Memorias del Primer Coloquio Latinoamericano sobre Arte No-Objetual y Arte Urbano, ed. Manrique, Víctor Manuel. (Medellín, Colombia: Fondo editorial Museo de Antioquia, Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín, 2011), p. 121.

Arkheion is Greek for “archive”.

This is a very rich topic, so we reviewed it in both meetings. Firstly, I would like to emphasize the selective role the curator played with regards to the materials, and their resulting decontextualization with respect to the relationships with other documents, funds, and collections. The other side of the coin concerns their value and accessibility with respect to new modes of symbolic and cultural relationships. Their placement also responds to changing formats and structures, such as the internet, digital repositories, collective tools for assigning topics, thesauri, and the gathering of collective references such as some Wikipedia entries; however, the digital sphere is still a space of accumulation immersed in a series of legal discussions about authorship, use, and custody, which in turn will radically modify the field of information, the document, and digital repositories. Likewise, the deployment of these documents in the reconstruction of art objects that allow an experience to be experienced again and therefore updated constitutes an important revision of the re-make. On the other hand, they also become objects in the collection, entailing decisions about their cataloging as artistic objects and their artistic reproduction, among others. The issue, I repeat, is wide and complex, but you can review the participation of all the guests of the first and second meetings in the publications produced by the Taller de Ediciones Económicas under a peer license. It can be accessed at: http://www.t-e-e.org/index.php/archivo/

Diana Taylor, The Archive and the Repertoire. Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. (Duke: Duke University Press, 2003), p. 326.

Comments

There are no coments available.