02.09.2019

Curator Fernando Escobar converses with the collective Helena Producciones about the strategies and operations that activate the archive created by the Cali Festival of Performance and the Escuela Móvil de Saberes (The Mobile School of Knowledge) in relation to its distribution through graphic reproduction and the media.

Visita guiada de Helena Producciones por la muestra Pasado tiempo futuro. Arte en Colombia en el siglo XXI, 2019. Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM). Imagen cortesía MAMM

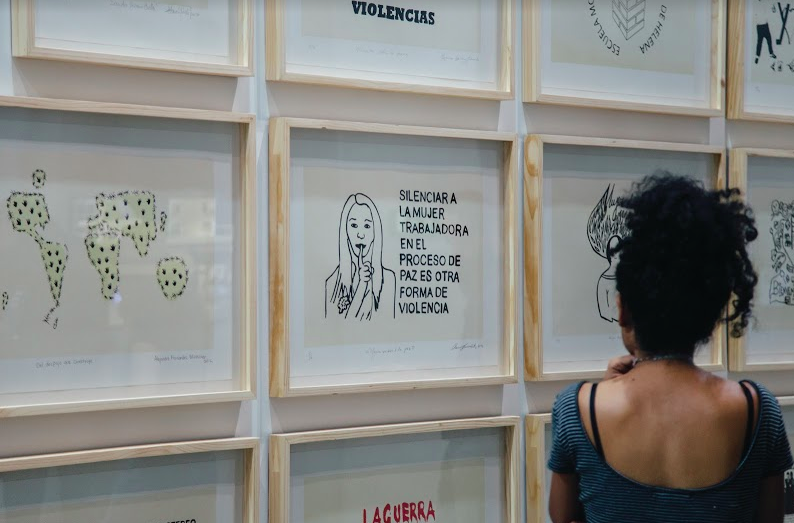

Helena Producciones, colección de 12 serigrafías, 2012. Con la participación de: Unión de Ciudadanas de Colombia, Escuela Ciudadana, Asociación de Mujeres Cabeza de Hogar, Central Unitaria de Trabajadores (CUT Valle), Arte Diverso, Fundación Nueva Luz, Junio Unicidad, Letincelle, Santamaria Fundación, Asociación Agencia Red Cultural, Ruta Pacifica de las Mujeres. Vista de montaje en Pasado tiempo futuro. Arte en Colombia en el siglo XXI, Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM), 2019. Imagen cortesía MAMM

Helena Producciones, 2015. Pintura en óleo sobre tela de una imagen de la obra Lona suspendida sobre la fachada de un edificio de Santiago Sierra, como parte del V Festival de Performance de Cali, 2002. Imagen cortesía del Archivo Helena Producciones

In Colombia for numerous reasons, there is no record of its artistic events, nor of its symbolic contents in relation to its political reality.

Visita guiada de Helena Producciones por la muestra Pasado tiempo futuro. Arte en Colombia en el siglo XXI, 2019. Museo de Arte Moderno de Medellín (MAMM). Imagen cortesía MAMM

La muestra fue curada por Alejandra Sarria, Carolina Chacón, José Roca, Jaime Cerón y María Isabel Rueda, coordinados a su vez por Emiliano Valdés, Curador en jefe del MAMM.

Como lo es el trabajo de José Alejandro Restrepo, Alberto Baraya, Ana María Montenegro, Sebastián Restrepo, el proyecto colectivo Echando lápiz, o el mismo Wilson Díaz individualmente.

http://www.helenaproducciones.org/index.php

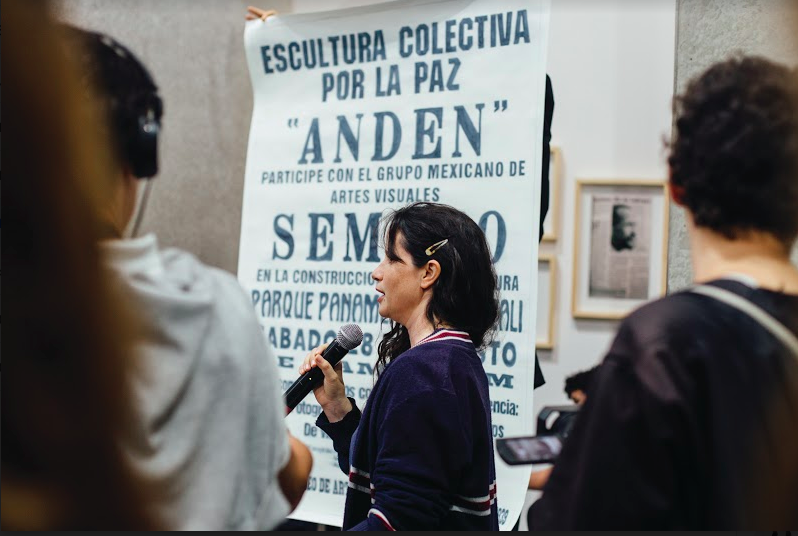

Andén es una acción convocada por SEMEFO a través de carteles y cuñas de radio, en las cuales se le pide al público asistente traer fotografías, ropa y objetos que hubieran pertenecido a sus familiares o amigos muertos a causa de actos violentos. Realizada en La Plaza de las Banderas de Cali, se abrió un segmento del piso y allí se empezaron a enterrar uno a uno estos objetos a lo largo de todo el día. Después de haberse llenado ese hueco, una tumba simbólica, se procedió a cerrarlo y a darle un acabado idéntico al que tenía.

Esta lona era una reproducción de la bandera de EE.UU. en una dimensión de 20 x 15 m. confeccionada en el Batallón Pichincha de Cali por el artesano Luis Abel Delgado y colgada sobre un muro exterior del Museo La Tertulia.

Pierre Pinoncelli anticipó su participación en el V Festival de Performance de Cali, anunciando, a través de una serie de anuncios radiales en las emisoras de RCN y Caracol, que desde Francia él vendría a Colombia para “rescatar a Ingrid Betancourt,” candidata a la presidencia secuestrada en 2002. Sin embargo, ante la imposibilidad de hacerlo, cerró el último día del festival auto-mutilándose el dedo meñique de su mano izquierda con un hacha, en una acción denominada Un dedo para Ingrid. Cabe mencionar que varios elementos utilizados por lxs artistas en diferentes acciones en el festival se integraron a la colección del Museo de Arte Moderno La Tertulia de Cali, entre ellos el dedo de Pierre Pinoncelli.

Cuando una obra artística sucede en un medio de comunicación con una audiencia que no está en contacto directo con el hecho cultural, a los ojos de lx consumidorx la obra puede o no acontecer, y lo que importa es la mirada que el medio realiza del hecho artístico, lo que deviene prácticamente en atentado contra la noticia. Ver en http://www.archivosenuso.org/ de la Red Conceptualismos del Sur.

Un carnaval contra la guerra, con obras de teatro callejero, comparsas y otras intervenciones públicas, montadas por ellxs mismxs. El paro abogaba por seguridad y visibilidad, y por la participación en el negocio de las basuras y el reciclaje, que años después se convirtió en un monopolio. Usando los medios de comunicación invitaron también a lxs ladronxs de “cuello blanco” a unírseles. Este evento fue entorpecido por el entonces alcalde de Cali, quien sacó un decreto de emergencia para impedirlo, lo que ocasionó un cambio de lugar de encuentro y la visibilidad de lxs ladronxs. Finalmente se conoció como “el día de no robo”.

José Vladimiro Nieto, un ex-indigente del autodenominado movimiento Los renovables, era en ese momento estudiante de primer año de Derecho en la Universidad Santiago de Cali. Tristemente, José Vladimiro fue asesinado tiempo después.

En dicha acción Tania Bruguera reunió un panel de actores relacionados con el conflicto colombiano para hablar sobre la construcción del “héroe”.

El taller de negociación, presentación e intercambio entre grupos sociales organizados se llevó a cabo en el marco del proyecto pedagógico del VIII Festival de Performance articulado con las charlas y la plataforma del festival, y contó con la participación de: Junio Unicidad, Unión de Ciudadanas de Colombia, Escuela Ciudadana, Ruta Pacífica de las Mujeres, Asociación de Mujeres Cabeza de Hogar de la Comuna 20, Central Unitaria de Trabajadores CUT, Arte Diverso, Fundación Nueva Luz, L’étincelle, Santamaría Fundación, Asociación Agencia Red Cultural Oriente Stereo.

Comments

There are no coments available.