28.09.2015

Based on Sergio González Rodríguez’s premises from “Campo de guerra”, Abaroa reflects on catastrophic representations in mass media, enquiring on the possibilities that contemporary art practices offer to tackle the most traumatic topics of an era.

I. A NOTION OF THE FIELD

Mexico’s recent history is marked by the emergence of extreme events that exceed authorities’—and collective Mexican society’s—capacity for response. The women who have been murdered in Ciudad Juárez; the forty-nine children burnt to death with impunity at the ABC daycare center; the forty-three students disappeared in Ayotzinapa; the young people killed in Mexico City’s bourgeois Narvarte neighbourhood; all are extraordinarily complex events and each could be taken as a point of departure for contemplating essential aspects of our times. These events seem to explode the coordinates of the imaginable; the everyday banality of the information machine retreats in the face of horror, or collective indignation on the part of millions. Other events, perhaps just as significant, have a less explosive effect but remain in the collective consciousness as stigmata or signs of mourning that are accepted as unavoidable fate.

After an apparent transition toward democracy, the return of priísmo (i.e., the Partido Revolucionario Insitucional—the PRI—and its wonted modus operandi) has meant, among other things, reactivating certain traditional control and censorship practices. Repression of public protest began the very day the current PRI president took office, and in the subsequent almost three years of his administration, not only have several inconvenient journalists been intimidated; television and radio programs have been cancelled and the predominance of an ossified communications oligopoly has grown more acute.(1) Journalism is an extraordinarily dangerous undertaking; this year three journalists have been killed. (2) Protections for this absolutely necessary activity grow ever more urgent.

Sergio González Rodríguez (b. 1950) was one of the first journalists to document early phases of organized crime escalation and political putrefaction in twenty-first century Mexico. (3) His essay Campo de Guerra (Battlefield, 2014) is a concise and extraordinary portrait of organized crime in Mexico. For its author, the existence of criminal networks such as the Sinaloa Cartel or the Zetas should not only be understood as an anomaly of Mexican culture but also as part of a complex global dynamic, a field he describes based on a number of the term’s different definitions: a territory, an energy field, a field of study, etc. The text’s greatest strength is that it works based on a multiplicity of viewpoints as well as a fluid interaction between different methodologies. Journalism intermingles with critical theory, psychology or history. Through these, González Rodríguez traces out a phenomenology of disaster that takes up everything from victims’ lived experiences to the administrative processes of violence in the new world order. The present text outlines how some artists in the “NAFTA zone” have explored problems that dovetail with González Rodríguez’s investigations using these artists’ signature interdisciplinary methods. My intent is to situate and activate “cross-pollination” between cultural activities that have become hybridized yet still maintain a certain distance from one another. Perhaps a recognition of this confluence can lend clarity to making out some sort of resistance mechanism.

II. BODIES IN SPACE

In Campo de Juego (Playing Field), journalistic information-gathering and personal experience(4) serve as points of departure for a reflection on the experiences of victims who are exposed to situations of extreme violence. In a chapter whose Spanish-language title translates to “The Anamorphosis of the Victim,” González Rodríguez points to the experience of a number of people (whom he calls “body/persons”) who were victims of crimes that have upset their everyday stability, which he contrasts with the law—a right that is presented as a symmetrical yet inaccessible order.(5) This space is no philosophical category, but rather a psychic experience that has implications for the victim as well as for the society in which the criminal catastrophe occurs. Faced with no access to justice, the victim disintegrates and lives the traumatic experience—“the anamorphosis of the irrational, of the a-rational, the horror and the panic of living something almost unutterable”—over and over again.

The subtlety and descriptive depth of this spatial relationship between law and trauma recalls a number of sculptures by US artist Bruce Nauman, in particular Room with My Soul Left Out, Room That Does Not Care (1984)(6), a room whose walls have been transformed into hallways; or indeed, different versions of Musical Chairs, realized starting in 1981, inspired by recollections of Jacobo Timerman, a distinguished Argentine journalist, published. Timerman was imprisoned and tortured during that nation’s years of dictatorship. The sculptures’ chairs and metal bars hang from the ceiling, physically occupying or blocking the space, and create an aesthetic distance based on what in the narrative was an affective distancing—an utter lack of compassion.

“I start and jolt in the chair, howling as electrical shocks continue to pierce my clothing. One time as I shake, I fall to the floor, dragging the chair behind me. They anger like children whose game has been interrupted and start insulting me again.”(7)

Timerman’s appalling first-hand account inspired the US-born artist’s first sculptures that evinced a political theme.(7) In these artworks, the psychological proximity or distance before an act of violence takes on form through crossbars and hallways; the perfection of its Platonic geometry is less relevant than the deformation of vital space through experience. González Rodríguez, the American sculptor and the Argentine editor share an obsession for calling up the rarefied kinesthesia of terror. Life for the victim of a crime, like the anamorphic skull in Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533), becomes incomprehensible, because what has changed, perhaps forever, is the viewpoint from which victims represent themselves.

These psychological dissociations are a common theme among other artists from the NAFTA zone (i.e., the battlefield in question). In a project entitled Recados póstumos (Posthumous Messages; 2006), Teresa Margolles places fragments of real suicide notes onto the marquees of Guadalajara’s abandoned movie theaters. The phrases can be cynical and banal (“I killed her because my friends told me she was cheating”), or pathetic (“adiós says the ugly, disgusting girl you always hated”). The exercise occupies a quite uncertain ethical position. Who asked those who killed themselves if their words could be used? But the result is a heartrending document of quotidian violence and misogyny as well as a reflection on private fantasies and the role they play in social settings. The posthumous message becomes spectacle (once it’s on the marquee as well as in the form of art), yet stripped of all idealization. As with Young Werther, the theme is not just death but also its disastrous repetition.

III. CRITICAL CARTOGRAPHIES

González Rodríguez—who also writes novels and moonlights as an art critic—has no qualms about embarking on the enormous task of deciphering the psychic reality that hides within actions and circumstances. To do so he relies on the weapons of the experienced journalist. It isn’t enough to record the number of victims; you also have to lend them a context that better illustrates their situation and that truly dimensions the crime, rather than normalizing it. “When you include victims in a space, when you spatialize them, a personal body emerges within a social body—a cultural topography and a critical spatial perspective.”(8)

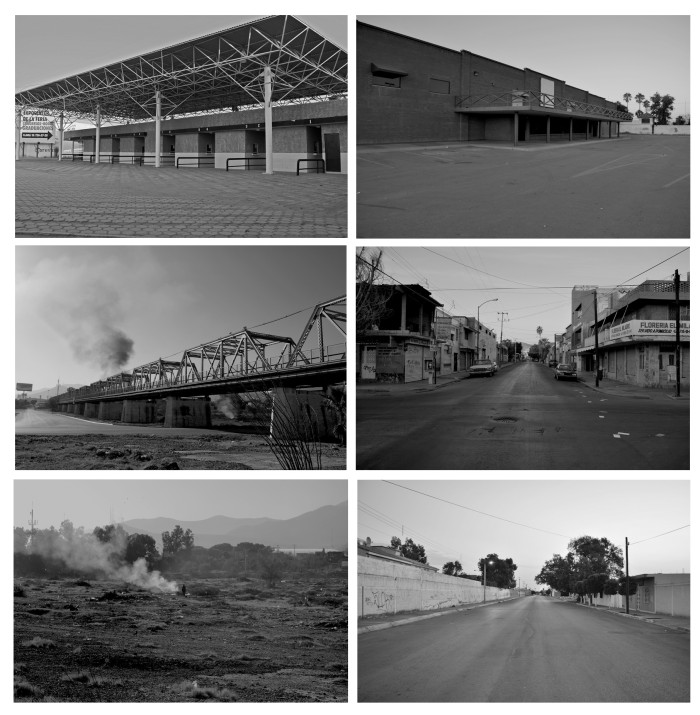

This interest in reconfiguring battlefield territory is what José Jiménez Ortiz has demonstrated in his short video artwork A Map Is Not a Territory (2011), which uses remarkable neutrality to document a number of places in Torreón, Coahuila, one of Mexico’s most violent places. This project lacks the theatricality of other attempts to capture the experience of living in a city criminal gangs have seized. In the artist’s words, his work

“[…] compiles a set of scenarios that have transformed a city’s day-to-day reality. It has to do with places whose value has changed completely, and out of which ways of moving through space have had to be restructured. Each of the sites the video goes to has witnessed violence that different Mexican cartels’ conflicting operations—their expansion and the proliferation of their middlemen—[causes].”(10)

Displaying dead bodies on streets and highways becomes an element of intimidation that transforms city inhabitants’ daily lives. People find themselves forced to change habitual ways, or adopt circuitous, more expensive routes. The atmosphere the video creates is jarringly sober, but when speaking of his work, Jiménez does not hide the anxiety that simply aiming his camera at a piece of violated terrain implies.

Campo de guerra describes Mexico’s immersion into a gradual militarization process deployed from the United States to other parts of the world. The young man forced into criminal gang activity because there are no work opportunities is just one part of the story. The immediacy of the narcomanta (i.e., hand-written messages inscribed on large, sheet-like banners that criminal organizations direct at the general populace) and indeed, their spelling errors, born of ignorance, is in keeping with drones, cutting-edge military technology and elite units that US armed forces have trained. González Rodríguez points to a terrible paradox: “Mexico has never been more insecure than now, when it enjoys the greatest human and material resources in its history for fighting criminal violence.”(11) The terror to which organized crime has given rise could not exist in this way without complicity on the part of the nation’s public and private powers. But González Rodríguez takes it further. His description places the phenomenon of organized crime as characteristic of the “new world order” he defines as “government and culture unanimously under the control of military, corporate and transnational financial elites, alongside their proletariat of bureaucrats and lackeys that defend the myth of incessant economic growth as universal panacea; the annihilation of natural and energy-related resources; exploitation of the individual through work and idleness; attacks on the sovereignty of the nation-state, etc.”(12)

And of course, all of it supported by US military and technological domination. American artist Trevor Paglen has recently redefined photography as a “seeing machine” and wonders, “How do we see the world with machines? What happens if we think of photography as image-making systems rather than just images? How will we need to think about images made by machines, for other machines?”(13) These are very good questions. His lens now aims at photographing US-government military and intelligence installations from a distance. As Paglen carefully elaborates a phenomenology of the society of control, he enables the machine—as it were—to oversee itself. This quest complements González Rodríguez’s attempt at multidisciplinary critique. The society of control is the terrifying future that our present determines. Yet in last year’s events at Ayotzinapa and with recent murders in Narvarte, the security cameras failed to work even though they were up and ready to go.

Notes:

(1) Examples of increasingly hardline censorship include interference in journalist Carmen Aristegui’s news broadcast; firing workers at the Canal 22 television channel and finally, Veracruz governor Javier Duarte’s threats and likely involvement in the murders of activist Nadia Vera and photojournalist Rubén Espinoza.

(2)Barómetro de Reporteros sin fronteras, http://es.rsf.org/el-barometro-de-la-libertad-de-prensa-periodistas-muertos.html?annee=2015, Mexico occupies the 148th place between 180 countries contemplated in the World Press Freedom Index and was the most dangerous country for reporters in the Western hemisphere.

(3) Huesos en el desierto (Bones in the Desert), published in 2002, is a rigorous investigation into the wave of murders perpetrated against women in Ciudad Juárez at the end of the 1990s, which opens a trilogy including El hombre sin cabeza (The Headless Man) and Campo de Guerra (Battlefield). The latter title was awarded the Anagrama essay prize for 2014.

(4) On several occasions González Rodríguez has reported having been the victim of harassment and violence.

(5) Ibid., pp 64-66.

(6) Cosje van Bruggen, Bruce Nauman, Rizzoli, NY, 1988; pp 21, 22 and 76. The author mentions Nauman read Jacobo Timerman’s 1981 book Preso sin nombre, celda sin número.

(7) Jacobo Timerman Preso sin nombre, celda sin número, 1981.

(8) See Noemi Smolik’s interview with Bruce Nauman: http://frieze-magazin.de/archiv/features/ein- amerikaner-in-duesseldorf/?lang=en , downloaded September 6, 2015.

(9) Ibid., p. XXX

(10) José Jiménez Ortiz, A Map is not a Territory, en Memorias del Simposiio internacional de teoría y arte contemporáneo, 2011, ed. Eduardo Abaroa, PAC, Mexico D.F. 2013.

(11) Ibid., p. 93.

(12) Ibid., p. 109.

(13) http://blog.fotomuseum.ch/2014/03/i-is-photography-over/ (downloaded 6 September 2015).

Comments

There are no coments available.