18.06.2018

Pêdra Costa and Fernanda Nogueira make a genealogy of the post-pornographic and sexually dissident practices that have resisted the alienation of the colonial project in Brazil.

From Pornochanchada to Post-Porn Terrorism in Brazil: From As Cangaceiras Eróticas to the Coiote Collective

On February 22, 2014, for the sixth edition of the Muestra Marrana in Barcelona, we presented some pornographic case studies that we will mention here. The Muestra was a conference for international DIY initiatives that fight to reinvent the current pornographic imagination using dissident discourses in artistic and cinematographic productions. This conversation was essential to the initiation of a dialogue between diverse sexual-political and gender dissident practices, mostly Latin American, and increasing visibility of the Coiote Collective’s work in Brazil. What could be a better context than the political moment of the World Cup to cast this sexorcizing spell? From our position of sexual exile, we observe increasingly blatant injustices and feel we must contribute by denouncing the events of the tropikal punk battleground. Káwó Kábíeèsíleè! [2]

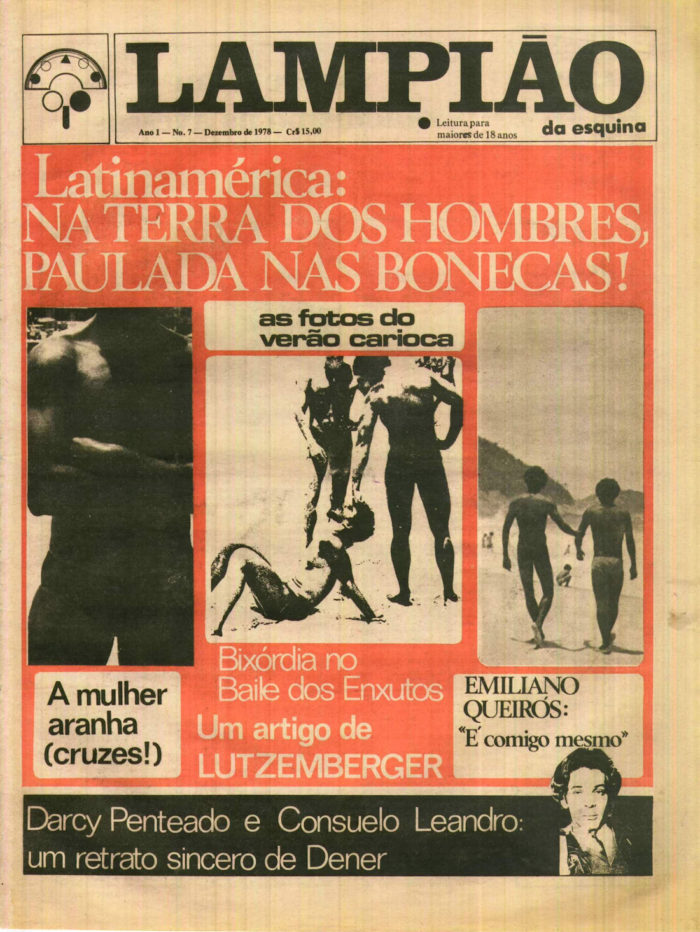

This writing emerged from a textual relationship, a movement of the ass, from follow-ups, fragments, vital impulses, convulsions, and questions on the authors’ social media accounts. It also emerged from the rage of seeing many people around us who were unaware of what has and continues to happen in our home country. While we listed and discussed works of art and artists, some fundamental questions about the sudaka [3] condition in Europe persisted: Why is it difficult to find narratives and information about post-pornographic and sexually dissident practices from the Global South? Why do we have more information about “subcultures” from the so-called “old” world than about the histories that took place and continue in us? Why are our subversive fictions and emancipatory realities invisible? What politics of invisibilization continues to act fiercely against aesthetic, sexual, gendered, communal, and social dissent? Who has interest in the mechanisms of invisibilization that affect these practices and incendiary subaltern narratives? The epistemologies of the sacred spaces of the Terreiros [4] all over Brazil, of the urban anti-gentrification occupations like la Flor do Asfalto in Rio de Janeiro, of places like La Boca do Lixo in the center of São Paulo, and of editorial initiatives that give visibility to sexual-political communities like Lampião da Esquina are not seen as valid by Eurocentric academicism.

If they still want to imprint us with the image of the strange/rare bug that appears at circuses or in museums, if it is a question of ignoring, invisibilizing, subjugating, or pointing out the difference to kill, enough! We have already invaded their territory with our “weapons and ammunition.”

Confronted by the lack of information concerning the repertoire that we are trying to connect in a large trans-temporal and regional network, we feel compelled to state that the colonial project not only segregates these dissident and emancipatory practices, it transforms them performatively into terrorist minorities before the heteropatriarchal, white, and normative dictatorship. Each context is a history of struggle. The colonial project promotes oblivion as well as the expropriation of knowledge. To revive, to remake, and recreate memory is to resist! This is where multiple forms of discursive memory intervention are included, as well as technologies of image reproduction, various types of media, and networks of open, free, autonomous, and anonymous circulation. When this barrier in the field of visibility is transposed, it is still necessary to confront the censorship and control of those who have contact with this material, as it is denounced to be suppressed. However, no matter what happens, we are still there. We act at the line of the equator and in the margins! Action is thought. The memory of the body and the legacies that we hold must find release, gain ground, create connections, and attract allies, destabilizing the certainties of the official centers of knowledge. Therefore, we must create our pirate editions of dissident subjectivations in this territory of resistance.

WARNING: our post-pornography does not begin with Annie Sprinkle! And it has no single date of birth like we are made to believe by the imperialist academicism that subjugates other temporalities to its own. Our “fag ethics” destroy the notions of pioneering, reproductivity, originality, copyright—concepts that consider everything else to be falsified and low-quality copies. We are copies for everyone! Lower your phallocentric power because the mission will be completed! Save PaguFunk! [5]

Fuck here! Pornochanchada’s moment

Let’s start with the marvelous Pornochanchada [6] and the possibilities of its videographic practice, disruptive discourses, and non-normative corporalities. The pornochanchada was born in Boca do Lixo in São Paulo, an area known for sex work, porn culture, and commerce, from which many actors emerged, later ending up in television careers. The screenplays combined eroticism, sensuality (starting with the sexualization of certain naked body parts), and sexual parody in a popular repertoire that attracted a massive audience to movie theaters in the city center.

Pornochanchada benefitted from the Lei da Obrigatoriedade [Compulsory Law], imposed by the dictatorship to prevent the influence of foreign cultural, aesthetic, and political productions. This law established that domestic cinematographic productions—which obviously passed through the control of censorship—would occupy film theaters for the greatest amount of time possible. It also required local films that were box office successes to remain in theaters until the moment that the film’s director expressed opposition to its continued screening.

This was also one of the motives and reasons for the end of street-porn film production. Although the government never financed the films (local businesspeople generally funded them in Boca do Lixo), the cinematographic policy in place ensured a financial return from the box office income. At the end of the military dictatorship, the Lei da Obrigatoriedade fell, and movie theaters were invaded by Hollywood productions and patriarchal/commercial porn, with explicit heteronormative sex scenes that hadn’t appeared in porno-chancha [porn-hoc] movies. It was a new reality that was fully compatible with the goal of implementing a neoliberal economy in the country imposing a canned subjectivity that drove mass consumption.

But how did these pornographic poetics emerge? Some Brazilian pornochanchadas devoured Italian smut with hot sauce and offered such a parody of conservative behavior in relation to sexualities and genders desired by the military regime at the height of the dictatorship. Acts of silencing and violence in the name of order and the standardization of life, without space for disagreement or the possibilities of social transformation, mostly brought about from above and to the left, marketed the political moment. Even so, pornochanchada succeeded in disseminating a tupiniquim critical philosophy; the “most basic deconstruction” that works through laughter, distance, and the estrangement provoked between the acting subject and the action, destabilizing naturalized behaviors and undermining familiar values.

Thus, films emerged that transgressed the conservative repertoire of European fairy tales and parodied the classics of American cinema with screenplays that confronted, for example, the privileged imaginary of the macho figure, sexist monogamous relationships, or showed the construction of femininity by parodying binary stereotypes of gender. [7] In the 1970s, the pornochanchada worked surreptitiously to change the minds of the consumer public, probably composed of heteronormative men. Yes, in Latin America paradox is a common occurrence: we can find emancipatory efforts bound to conservative strength, in the same body and discourse. Such was the case for pornochanchada.

As Cangaceiras Eróticas

The film that most interests us is As Cangaceiras Eróticas [The Feminine Erotic Gang of Hinterland Punishers]. The narrative takes place in north-eastern Brazil, an area strongly stigmatized by the economic centers of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo in that era. The screenplay doesn’t take place in an urban setting, but rather in areas where coronelismo [8] and armed (in)justice reign. Filmed in 1974 under the direction of Roberto Mauro, this film not only reincarnated the marginal heroic figure of the Cangaceirxs, but it also upset any conservative notion of what a woman could be. It is a narrative that confronts the systemically imposed discourse of feminine sweetness, women’s place of action, and the roles they play in society. In the first minutes of the movie, the dialogue is powerful, with characters issuing such remarks as “Is women’s only destiny to end up in the kitchen or sewing?!” or even “Are you coming with us? Or would you rather go to the city to be enslaved by jealous bosses and husbands?” These statements are made by one of the women characters who takes on a leadership role in the group’s actions until the end of the film. However, although certain patriarchal expectations are challenged in the movie, other heteronormative characteristics are reinforced.

The organized, programmatic, and just direct action of the cangaceiras shows “the machismo of every single day.” A journalist in the community reveals the great malaise that challenges the women’s emancipation: “Shame doesn’t allow us to leave the house…and to put an end to this demoralization, it is necessary that we exterminate this group of erotic cangaceiras. I suggest we organize a crusade against this band of sexual delinquents.” Or threats that clearly show the terrorist force of the cangaceiras as they confront the established patriarchal order: “We’ll extinguish those macho women once and for all.” At the end of the film, the screenplay includes the phrase that directly links this text to the movie: The legend can’t be stopped!

The Gang of the Porn-Art Movement and the Strip-tease of Art

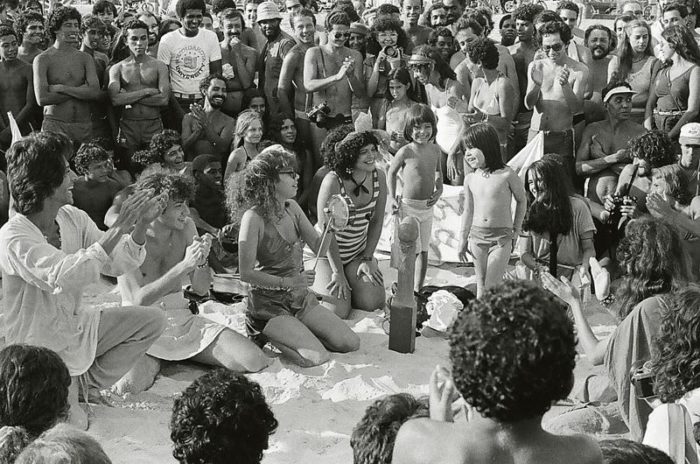

Between 1980 and 1984, the Movimento de Arte Pornô [Porn-Art Movement, hereafter MAP] [9] was producing and acting in opposition to the repression and standardization of bodies. This movement intensified during the country’s military dictatorship (1964-1985), and intervened in the castrating/castrated Brazilian imaginary. Their poetic and performative program sought to subvert regimes of sexual visibility and promote new tactics for action. The proposal of the Gang, the performative branch of the Movement, was to release art and literature from their conventional spaces and present them in a provocative way, with the body, in public areas. The artist collective’s guerrilla tactics included interventions in theaters, plazas, beaches, and public meetings at Cinelandia, the pulsating and socially contradictory heart of Rio, among other locations.

The participants produced pocketbooks, stickers, comics, fanzines, t-shirts, postcards, poem-objects, posters, and other artworks that also circulated through the mail art network, taking advantage of all graphic mediums available. Publications that bring together the notes and performative experiences of the Movement, that sought to strongly change the public’s perception of the body and language in an environment still restricted by moral conservatism and political repression.

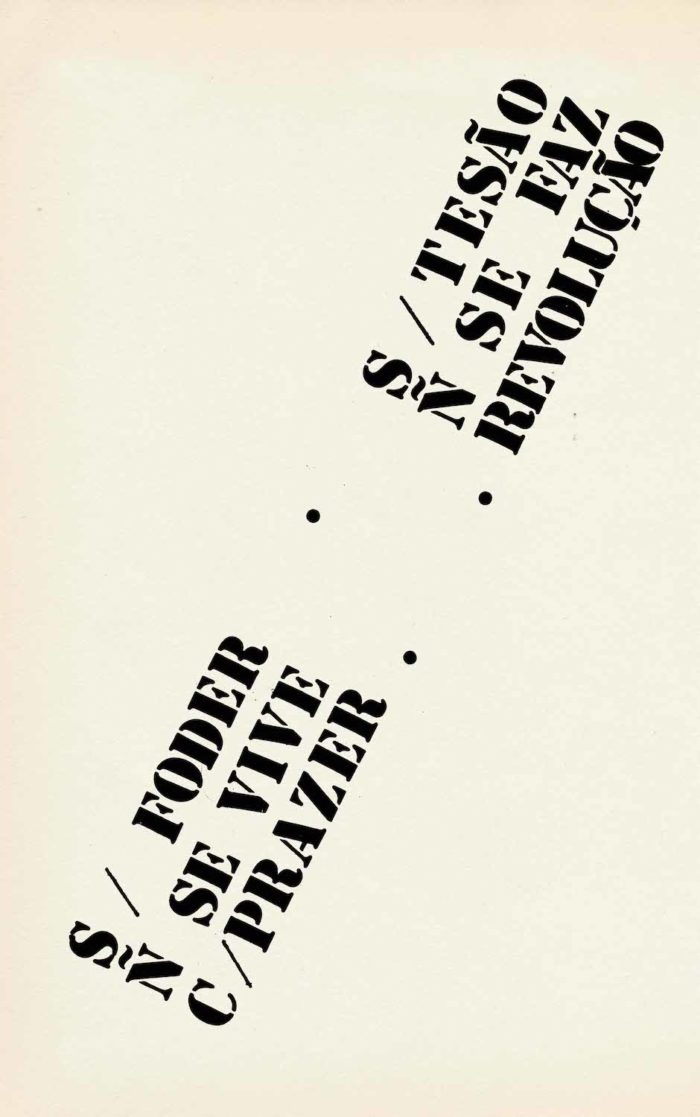

The expressions of the Movimento de Arte Pornô were opposed to the literary orthodoxy, as they included protests that promoted new lifestyles, behaviors, and creativity. At that moment, the “pornographic” appeared already as a condemnable notion, bound by negative connotations. The MAP, however, worked with those elements that exalt the libido, sensuality, affective and emancipatory relationships to deconstruct the censorship that erased and despised these relationships in everyday language, and to call for the subversion of traditional pornography. At the same time, the Movement sought to call attention to the dangerous presence of expressions and words like torture, disappearance, power, censorship, misery, and hunger that had been normalized during the dictatorship. In this context, the Gang aimed to provoke a “defamiliarization” of the body and the word. No word didn’t deserve to be used just as no part of the body should be censured. The group thus sought to destabilize the authoritarian standardization that had contaminated the body and effectively turned dictatorial censorship of information and political debates into increasingly generalized self-censorship.

The Gang of the MAP, a short-lived collective of strategic action, searched for creative ways to create fissures in the power structure and directly counteract the castrating severity that the totalitarian State had tried to instill during the past seventeen years of dictatorship.

Tropikaos Anarko-punk-kúia Post-porno-terrorist Decolonization

We cannot help but mention two crucial movies: Vera (1986) [10] and Meu amigo Cláudia (2009) [11]. It is impossible to end this article without first referring to a wave of artists who are now confronting hegemonic modes of subjectivation. First, Solange, tô aberta!, a dragpunk-funk project that was born in Salvador in 2006 and features disruptive desires in a set of bodies, parodying the construction of gender binaries, and valorizing Carioca funk. We mention this project because it is affectively connected to spaces and the actions of artists and activists like Jota Mombaça, la Musa Michelle Mattiuzzi, la Casa Selvática, el Espaço Impróprio [12], the gay punk band Gay-OHazard, Taís Lobo’s project Antropofagia Icamiaba, Kleper Reis and their Cu é Lindo, el Bloco Livre Reciclato, el Museo de Colagens Urbanas, AnarcoFunk, Teatro de Operações, Coletivo Coiote, homeless people, and more.

In the Barcelona presentation we mentioned at the beginning of this text, our focus was primarily the Coletivo Coiote. The actions of the group represent something utterly confrontational in a field of aesthetic, political, and experimental constructions like the show Marrana, an international reference for the post-porn community. The Coletivo Coiote generates a particular real and symbolic space for denouncements in Brazil, and it dares to strike up a confrontation that acts at the nucleus of colonial structures of domination. Through direct performative action, the Coiote promotes one of the most radical artistic proposals in Brazil in attempting to demonstrate that coloniality persists in the social body.

The visibility of the Coletivo Coiote on the international stage at a post-porn DIY event, in addition to helping make visible Brazil’s post-porn terrorism, was a political decision. It called attention to the need to think about strategies for anti-system trans-border solidarity among sex activist groups, even in Brazil, the setting of the terrorist-tropikaos-post-porn. This political decision is what motivated this article.

—

[1] An extended version of this article was published in issue 5 of the Revista Rosa, a special edition dedicated to post-pornography in December 2014. Available (in Portuguese) at https://medium.com/revista-rosa-5.

[2] Káwó Kábíeèsíleè is a Yoruba expression. In Brazil, it is usually translated as “Welcome to the King of Earth.” It also means “admire and contemplate he who knows the response to all questions before they existed on the face of the earth.”

[3] Translator’s note: Sudaka is a modification of sudaca, a pejorative term that comes from “sudamericano,” a person from South America.

[4] Terreiro in Afro-Brazilian cultures is a holy place where altars built and ceremonial practices are carried out to the Orishas.

[5] PaguFunk is a feminist funk group in which women from the periphery of Rio de Janeiro sing about their daily lives. Cf. <https://soundcloud.com/pagufunk>

[6] Translator’s note: Pornochanchada is a genre of comedic sex films, the word’s roots are porno and chanchada, a Brazilian variant of slapstick comedy.

[7] Some examples of the genre: Histórias que as nossas babás NÃO contavam [Stories that our nannies didn’t tell] (1979), A Banana mecânica [The mechanical banana] (1974), Nos tempos da Vaselina [In the days of Vaseline] (1979), Dona Flor e seus dois maridos [Mrs. Flor and her two husbands] (1976), A Super Fêmea [The super female] (1973), Caçadas Eróticas [Erotic Hunts] (1984), Cada um dá o que tem [Each one gives what s/he has] (1975), As rainhas da pornografia [The queens of porn] (1984), A dama do lotação [The lady of public transportation] (1978), A noite das taras [The night of Perversion] (1980), Gente que transa… os imorais [People who Fuck… The immorals] (1974), Elas são do baralho [These women are awesome] (1977), O bem dotado – o homem de Itu [The gifted… the man from Itu] (1978).

[8] Translator’s note: Coronelismo was the system of machine politics in Brazil under the Old Republic (1889-1930). Known also as the “rule of the coronels”, the term referred to the classic boss system under which the control of patronage was centralized in the hands of a locally dominant oligarch known as a “coronel”, particularly under Brazil’s Old Republic, who would dispense favors in return for loyalty. Source: Wikipedia.

[9] The collective included the following members: Eduardo Kac, el “Bufão do Escracho” [Buffoon of Slapstick Humor, Brickbat Buffoon]; Cairo de Assis Trindade, “Príncipe Pornô” [Porn Prince]; Teresa Jardim, “Dama da Bandalha” [Dame of Dereliction]; Denise Henriques de Assis Trindade, “Princesa Pornô” [Porn Princess]; Sandra Terra, “Lady Bagaceira” [Lady Hooch]; Ana Miranda, “Cigana Sacana” [Vampy Tramp]; Cynthia Dorneles, and the “Surubins” [Orgyrubs], the kids Joana Jardim and Daniel Trindade.

[10] Vera, directed by Sérgio Toledo, is based on the true story of a trans man, Anderson Bigode Herzer, who wrote a book entitled A queda para o alto [The fall to the top], which was published in 1982.

[11] The documentary directed by Dácio Pinheiro depicted the life of Cláudia Wonder. Cláudia began her artistic career in night cabarets in Boca do Lixo and was the first trans person to participate in Pornochanchada movies. She was also an icon in the fight for trans rights in Brazil.

[12] Espaço Impróprio (2003-2011) was an a anarcho-punk house in São Paulo that held the first queer events in Brazil.

Comments

There are no coments available.