28.03.2022

Andrei Fernandez constellates, from Ogwa’s work, the powers of indigenous art despite the history of Western art, to reveal an autonomy of representation that explodes into all that time can be.

TREMORS OF THE REFLECTIONS OF THE FUTURE

There are temporal conceptions, as in the case of the Guaraní people, in which abstract futures are superimposed and where pasts that could have occurred, as well as presents that could be occurring in parallel scenes, transpire. José Lezama Lima distinguished remembrance as an act of reconstitution of what was and memory as a metaphorical act that intervenes not only in the imagination of the people who embody it but also in the sense of relevance that the past has for the present. Thus, as Silvia Cusicanqui reflects on a text by Walter Benjamin: the past can ignite in the present the explosive materials of what has been and cease to be archaeological, to become a political category capable of shaking the now, to become a retroactive time.

Working in the Chaco of Salta,[1] I became aware of the confrontation of different times and memories that ignore and at the same time confront each other, as happens in many places of the American continent, in the permanent dispute over the understanding of how the ways of life and the “resources” of the territories are composed and intertwined for their management. I recently visited one of the communities of La Puntana, on the banks of the Pilcomayo River, where I asked a group of women of the Wichí people[2] what they call in their language the action of weaving; after talking among themselves without easily agreeing, they explained to me that notechel is the word in their language that would mean “ancestral” and that ta otache is equivalent to “future,” or rather means “forward,” and that it would be necessary to join them in order to explain their work of creating images with linked threads. They understand it as a work that carries the ancestral forward. Juan Díaz Pas, a poet from Salta, points out to me a constant in what we can call Indigenous art, its conceptual gamble: the creation of a temporality that’s very precise but for which there is still no name in Spanish. He proposes to call it futurancestral.

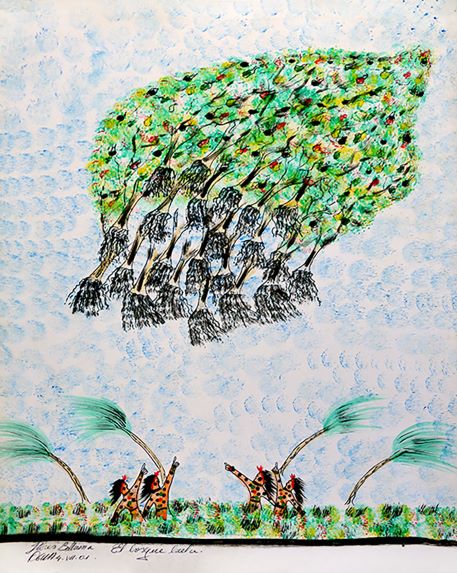

In a conversation with Almada, Ogwa explains an image he created: a forest that flies. The mountain, the islands, different trees, each one with its partner, come out to the earth making a tremendous noise that he believes his ancestors watched, witnessing how the forest simply: went away. That image is part of the history of their people. The whisper of collective memory that says the forests are going to end. Ogwa warns that this image is something to keep, as if to make a deposit of the forest for the future, and states that the elders of his people wanted to know what for? what is the future? what were these new times meant to be?

THE CHANNELS OF PRESENCE

There is one of the 150 reproductions of Ogwa’s works in the digital catalog that archives the collection of the Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro in which one can only see an accumulation of undulating lines that suggest a human form invaded by other forms that blur it without letting it lose its humanity. The interpretation of this drawing in its file indicates that it is the illustration of a mónene, a story equivalent to what in western literature would be a tale. The Ishir narrative contemplates different genres: the saga of the great myths, the shamanic literature and the minor stories linked to the previous genres but aimed at entertainment, the teaching of rules, and the stimulation of the imagination.

This narrative is dominated by stories of grand adventures and extraordinary acts starring shamans, but the tale that this image refers to is that of a feminine mountain spirit called Pokórshta, a force with the appearance of a woman who was an adversary of the jaguar. In this scene, since the feline would not let her approach a watering hole to drink, Pokórshta had smeared her body with honey and covered herself with leaves; under this disguise, she managed to deceive the jaguar by camouflaging herself with the landscape. This form, that of strength as a woman smeared with honey and covered with leaves, is what Ogwa’s drawing portrays.

He captured these figures on paper, as other Indigenous peoples of Paraguay have done since the twentieth century[4] as part of the changes produced by European colonization— substitutions and forced or seduced appropriations which gave rise to the phenomena of incorporation of images, solutions, procedures in which the perceptive schemes of the Indigenous peoples of the Gran Chaco and Indigenous frameworks of meaning are still present: a variety of senses and narrative times, simultaneity of real and fictitious references. But they also mean a reinterpretation made by each author of their own culture from a new expressive medium: the western drawing.

The Museo del Barro, after decades of collective research and dialogue with different communities and cultural institutions, affirms that it is necessary to name Indigenous art as an art form that is not outside other dimensions of culture. They emphasize that it is essential for these peoples to face and assume the changes in their territories based on collective memory and their own expressive needs, since the innovations that the communities introduce in their cultures mobilize their imaginaries and dignify new links with others, new languages. From this point of view, art allows people belonging to Indigenous communities to not only be seen through the poverty and lack that condition their way of living in the present, but it gives them the possibility of being considered creators, makers of different symbols, capable, but above all: with the right to complexify, to enrich, the global cultural heritage.

Ticio Escobar asks a fundamental question:

In what sense can the artistic be named in relation to cultures in which beauty—as an aesthetic form—cannot be separated from the other moments that make up the social complex?

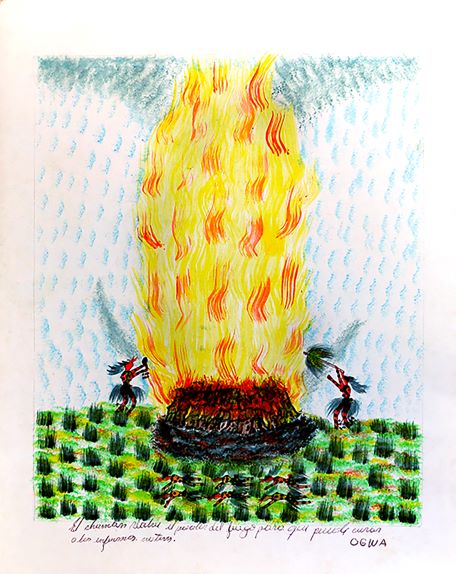

He points out that the concept of “art” refers to practices that generate an immediate significance of things, in order to intensify the experience of the world. When I asked Caístulo, also called Juan de Dios López and Juayuk,[6] if he knew what “art” was, he told me:

Art is a fire that makes you step on a thorn, or burn with the same art. A fighter walks and the burning thorn that is art enters his body . Wounded, he falls in love with everything he sees, and begins to imagine drawings when he meets those mother’s songs that made life grow. He goes mad with the desire to be another, loving, and the spirits fulfill his desire by transforming him. He recognizes himself as someone else, but his desire to change continues. Could it be that he dies as if he were still alive?

Ogwa described his artistic practice as remembering and painting what is engraved in his thoughts, the senses of his ancestors and what he felt for them. He imagines and invents, but is it possible to imagine what is not known? An image can be a gesture that transforms time, an act in history and on history, a seeing of possibilities to imagine freedom.

Is it possible to transform oneself through artistic practices, through the processes of patrimonialization, the ways of imagining? What we call “otherness” appears to us in the form of vestiges that question our perceptive certainties, which we complete with capricious or simply limited inventions that we also call “imagination.”

Otherness always continues to question us.

Going through reproductions and interpretations of Ogwa’s works, I cross the porous borders that define countries and return to the Chaco of Salta and to Caístulo’s questions and indications:

I am left with a rough understanding of the presence of invisible specters, that request that Caístulo transmits to understand fragility in the face of the dispute between powers and forces that shape our present, to immerse myself in the mountain paths that open other possibilities for experiencing the world, paths in which it is easy to get lost and feel something like this, which the poet Juan L. Ortiz wrote:

Name given to the Gran Chaco Americano area that corresponds to the province of Salta in northern Argentina, in the border area with Bolivia and Paraguay.

They are part of the Thañí/Viene del monte collective: https://vienedelmonte.com.ar/.

“(. . .) The sisters came with a bag. (. . .) For us clothes and something so you don’t get bitten by mosquitoes anymore. And I told our grandfather, but he said no, no, no, because those people come to eat us. They didn’t know. So the sisters opened the bag . . . it was candy. And they grab and throw us, they throw candies to us like chickens, and then they peel one and show, and one says look at this one and she eats it. Then the grandparents look and eat too, and there they come out, they come tamed, and they are tamed and come right away, but they were naked.” Testimony of Ogwa. Adriana Almada, ed. Premio Jacinto Rivero. Obras premiadas y seleccionadas. (Asunción: Ediciones Faro para las Artes, 2002), 115-118.

Lía Colombino points out that drawing existed before among the Indigenous peoples, but it was (and is) done on other surfaces: on the skin, the earth, fabric, etc.

Arte 360 Grados, “Art is Not Innocent,” Terremoto, November 15, 2021, https://terremoto.mx/en/revista/el-arte-no-es-inocente.

An activist from a peri-urban community of the Wichí people in Tartagal, Northern Argentina, who has the spiritual ability to listen to the messages of the winds and trees, and the wisdom to carry out reforestation and hybridization of native species.

Text based on notes from Caistulo’s messages sent by WhatsApp and recorded by Dani Zelko as part of the project La escucha y los vientos (2020/2021).

Comments

There are no coments available.