Issue 19: Planetary Solidarity - Modernidad

Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran, Jo Ying Peng

Reading time: 13 minutes

15.02.2021

Revisiting the impacts of modern developmentalism located in Asia, curator Jo Ying Peng, guest editor for the second part of this issue, reflects on artist Kao Jun Honn’s socially engaged practices and invites curator Arlette Quynh-Anh Tran to talk about how Art Labor’s project “Jrai Drew” was made in the Central Highlands of Vietnam.

Back in 2014 in Taipei, I and my colleagues from TCAC (Taipei Contemporary Art Center) set up the “Art organizations’ joint office” opposite the parliament in support of the Sunflower Student Movement. The student protest was against a trade pact with China that would hurt Taiwan’s economy and leave it vulnerable to political pressure from Beijing. The action that initiated the movement took place overnight when students broke into the parliament and occupied it. Within a short time, we gathered a tent and power generator to be on standby on the streets, then contacted a few writers for contributing texts to the campaign. Kao was one of them. Shortly I received his text titled Boai Market that tells the labor history of his mother. The artist was nurtured by the Boai Market where his mother earned a living by selling women’s underwear. Since the 90s, when the age of neoliberalism arrived on our island, domestic products have been unsalable, replaced by cheap underwear imported from China. Kao’s mother lost business, the market collapsed, then she developed Parkinson’s disease and was forced into unemployment.

“Did you remember that I mentioned artist Kao Jun Honn was researching the Topa Tribe? The location of the relic is very close to the village you were born.” Before drafting this letter, I happened to spot Kao’s new publication Llyung Topa which is part of his ongoing activist project that began after Boai and is about to reveal the little known history behind Topa, an aboriginal village that was devastated completely by a violent reclamation project during Japanese-occupied period a hundred years ago. It is almost a blank page in the history of resistance. I have never heard about it, neither has my father who is half aboriginal. The dwindling presence of identity does little for recognizing ourselves but says much on the contradiction of who we are. I could understand the loose link that hardly ties my father with his root, not only because he has been living in an urbanized way most of his life, but more to do with what he feels he is. While we are yet to discover our traces, Kao has been uncovering the past trails by tracing them with his feet as he enters mountains, forests, and remains.

Is this a way to unlearn, to step on a path, to repair?

In a country like Vietnam, where wars covered almost the entire history of this country’s several-thousand-year existence, nation-building thus has been an obsession due to its vulnerable state from invasion and destruction. So whenever the situation was a little bit quiet, even pretended so, for example in the early 1960s during the recent separation of North and South Vietnam, each side’s government urged and encouraged their people to labor at most. And the government turned around, sought for Right ideologies and Modern development models, amid the spilling dangerous wave of Cold War. Later, I still remember the late 1990s; in our Geography classes, we had to memorize the location and density of the rich natural resources in Vietnam; hence arouse the pride of our ancestors’ “Golden forest – Silver sea”[2] to find a way to modernize the homeland. During those, we were lectured about the illegal deforestation of the ethnic minority communities, that they burned forests for cultivation. It was their fault that the forests aka our national treasures have gone. I still recall me, a 10-year-old kid, very angry at their anti-science way of farming as destruction. By the early 2000s, the media began to report on the process of the state quickly quelling the riots of ethnic minorities in the Central Highlands—where the Jrai people live—simply for their “reactionary conspiracy.” Perhaps, without my later encounter with Truong Cong Tung’s family and friends in the Central Highlands, I would never understand the cost of the above propaganda for assimilation to speed up modernization through so-called science pedagogy.[3] That pseudo-science depicted the image of a “different” Vietnamese—the other—the ethnic minority communities like the unscientific people who are hurting nature. Combined with the nationalistic spirit, it created the message that the Kinh—the country’s major ethnic group, with a new penetrating free socialist-oriented market—will save both nature and these backward people with more scientific solutions, as well as their cultural traditions in the national discourse of “reinvented heritage.”

Going back to your questions about the Art Labor, they remind me of the exchange with Nelson Carlo de Los Santos Arias—my film professor at CalArts, a Dominican filmmaker—about similar ideas between Latin American and our region. I ventured to cite those thoughts with you: One time, Thao Nguyen & Cong Tung, two members of Art Labor, sent me a video of Brother Dieh sitting and singing beside the firelight. Looking at the curious faces of Kinh people around him, Dieh laughed and interpreted his song into Vietnamese: “I love you (female pronoun to male)/ I love you (male pronoun to female)/ Don’t leave each other / You die / I die / One dies first and the other must remember.”

As Glissant’s understanding of the history of non-Western countries, tracing human life in the rotation of the universe order, like the tracing of people origin in Latin American context, is impossible.

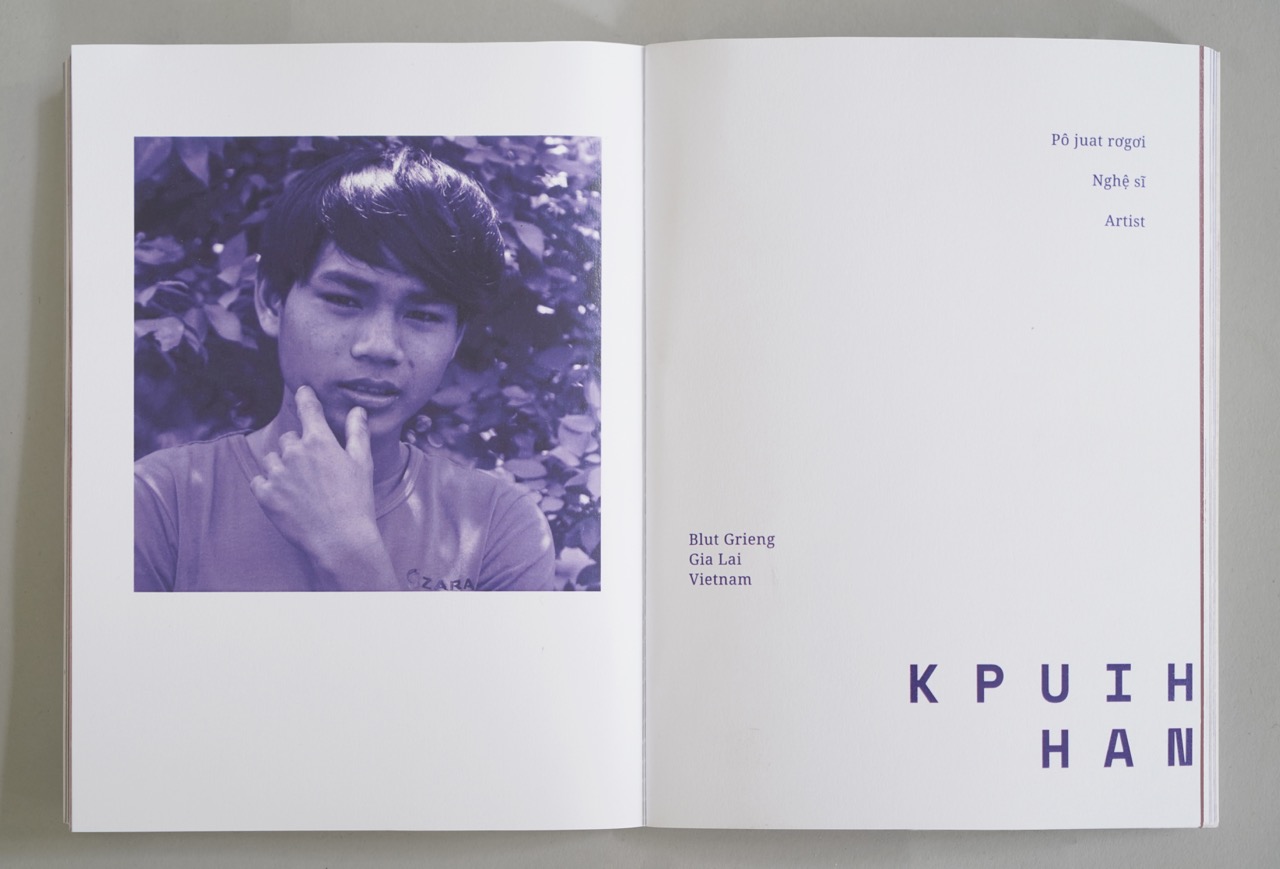

We—the art collective—borrow the idea of death in the Jrai’s cosmic belief to understand what is happening in the Central Highlands region, where the Jrai community lives alternating with the Kinh like us. It has been 4 years since we decided to go to the Central Highlands—the hometown of a team member—to learn, build relationships and carry out projects with the Jrai community, the neighbors near his family. The folk artists sculpted the statues, we organized celebrations and exhibitions for them in the villages so that relatives and family, friends can come to see and have fun. We made films about the Central Highlands, about the lives of Kinh and Jrai farmers. They went to overseas exhibitions with us. The understanding among people in the group does not lie solely in the language, because in fact, that linguistic gap is still difficult to fill. The beginning of our relationship is the separation—demarcation between urban and rural people, between Kinh people and ethnic minorities, between Vietnamese and Jrai language. After four years, it is reflected in the sharing of the chickens, the eggs, the sculptures, the book, and the trust of them to travel with us. Interestingly, death itself is the beginning of everything. Four years ago, we caught sight of a beautiful tomb on the edge of the forest and then traced the person who carved it. We followed the evaporation breeze of the dewdrop.

Warmly,

A

This line has been extracted from the title of Jiahui Zeng’s essay Naoki SakaixGe Sun: Europe is responsible for the production of theory and Asia is responsible for the production of experience? The essay is written and published in Chinese and based on the discussions from the lecture by Naoki Sakai and Ge Sun. The event is organized by Inside-Out Art Museum as the program of the exhibition Discordant Harmony (2018).

Is a Vietnamese idiom that honors the country’s treasure of natural resources from the mountains to the coastal regions. During his lifetime, Ho Chi Minh often used this phrase to appeal to national pride.

Modern factors such as electricity—especially hydropower plants and industrial plantations—are considered as science applied in socio-economic development and reform. Therefore, in general education, especially in geography, this kind of information is disseminated at the same time describing bias the indigenous community.

Bruno Latour, We Have Never Been Modern, trans. by Catherine Porter (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 1993), p. 99.

Comments

There are no coments available.