23.07.2018

The collective GARRILLAS / desperate.awaited complicities from their experience in the First International Gathering of Politics, Art, Sport, and Culture for Women in Strive question the use and action of spaces from urban individuality in contrast to the collective proposal of Zapatista women.

Fire Conversations in the Hills: Collective Un/Learnings for the Agreement to Live

The idea of this intervention as a collective and anonymous bid originates from the un/learnings acquired from our shared experiences at the Primer Encuentro Internacional, Político, Artístico, Deportivo y Cultural de Mujeres que Luchan [First International Gathering of Politics, Art, Sport, and Culture for Women in Strive]. The gathering was organized by Zapatista women and celebrated on March 8, 9 and 10, 2018 at the Caracol de Morelia, Tzotz Choj zone, Chiapas, Mexico. This is why, in this text, we conceive of ourselves as a (female) body [cuerpa] and a collective (female) subject [sujeta], in order to behead individual subjectivity, to engage with the anonymous stand of the Zapatista proposal, and to unfold agency from the individual revolutionary subject [sujeto] who is young, male, white and upper-class. This is an intervention, because more than being an article in a magazine, it is a pretext to deal with all those feelings and thoughts that came upon us in the hills of Chiapas, while we shared our fire amongst women. That is, this text is an attempt to translate what engulfed us at that moment, and to keep pushing it forward to give it continuity.

At the beginning of the Gathering, materializing their collective body, the Zapatistas joined hands and symbolically entered the Caracol [1]. They wore colored ribbon bows on their black ski masks. The colors indicated to which of the Caracoles they belonged, but they showed up as a common body, as a plural collectivity. We insist on the collective stand as methodology because it activates the affective, the visual and the political, and because we think it is one of the possible ways to survive and transgress the modern capitalist project. We believe that, to be transformative, a project needs to be carried out with others.

This text was built from a series of conversations, that as performative strategies made it possible to incorporate/incarnate/spark off the orality of the un/learnings we recognized thanks to the Gathering. We believe this gesture is important, because to activate from orality is to activate the possibility of listening, of being present, and other forms of articulating temporalities which enable relationships and make intervention on others possible. Conversations physically induce feelings, emotions and survival strategies. Conversation matters to us because it bears the possibility of being redundant, ambiguous, unfinished. When carried out informally, it makes room for unverified information such as gossip, which escapes from legitimate forms of knowledge production. To retake this strategy is to reveal the fact that this production is always partial and collective.

We acknowledge that at this very moment we are translating from our own orality, by thinking about this Gathering of Women in Strive we attended and in which many contradictory things happened. We are aware that we are shifting our observations towards other spaces, without being able to include all the voices that were present. Careful with romanticizing!

We remained three days at the Caracol. This place symbolically and materially allows practices such as dialogue, reflection, and meetings to have different ways and rhythms from those allowed by private property. Some of the most important lessons of the Gathering were learned by observing the way these spaces are constructed and treated. Flexibility and plainness turned it into our sleeping place at night, and into a football court, a workshop or a discussion forum during the day. At other moments the place could be used to stage a spiritual ritual or a dance. The Gathering proved that in very specific communitarian structures, spaces are open to the necessities that may arise, as opposed to urban architectural spaces, especially museums, galleries and academic venues, wherein only certain activities for a certain public can take place. To rethink spaces in the perspective of the collective and communal needs deprives them of their hierarchy: the space does not define what you do, but, on the contrary, what you do is what defines the space.

They summoned an encounter on their own territories, of which they know the necessities and responsibilities. As such, we were required to take responsibility for our manners, our schedules and our spaces. This leads us to a fundamental question: How do we activate our spaces? How are we building them? What does it imply, in terms of responsibilities, to arrive and occupy a place that is not ours? All this because during the Gathering there were consistent ways to do so, and others that weren’t (at all).

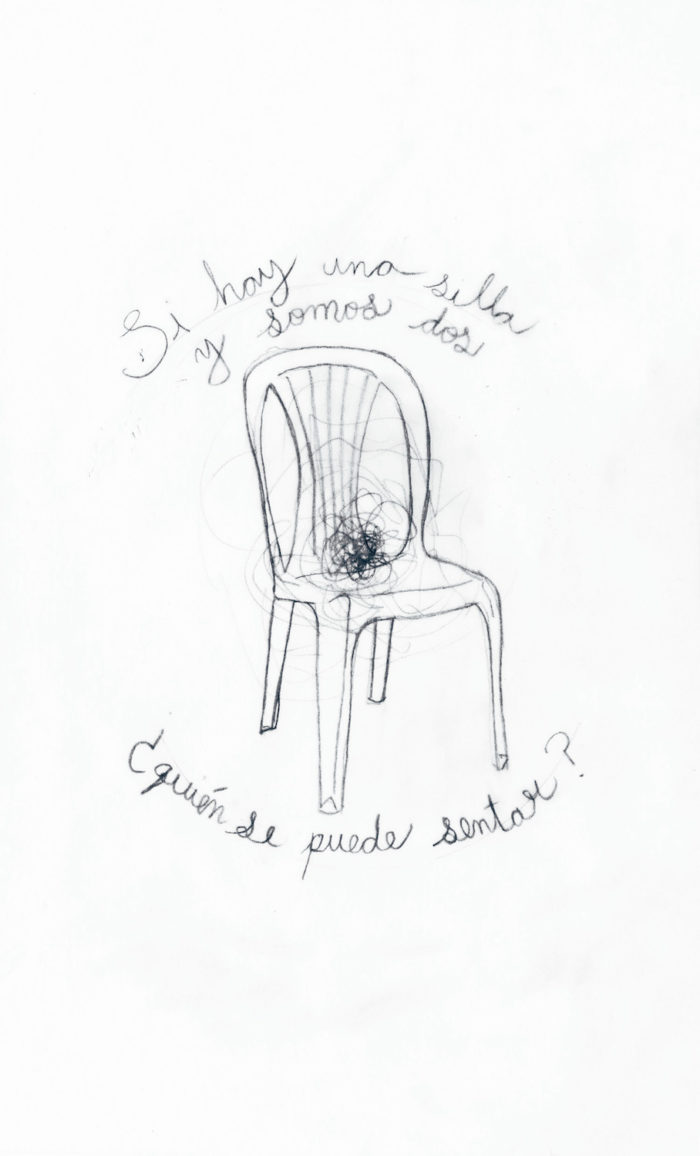

One symptom among many: at a gynecological self-examination workshop, the instructor, overwhelmed by the number of participants, asked us to leave the first two rows vacant for the Zapatistas. When this was done, a few persons with colonialist attitudes (white women, or women with bodies that are historically linked to privilege) proceeded to occupy the seats. When they were asked to move, they disagreed or argued that the Zapatistas did not want to occupy them. The idea was precisely to leave the seats empty, even if none of the Zapatista comrades wished to sit there! This was supposed to allude to the way certain bodies have been historically excluded from these spaces, and to act consistently.

Why the need to ask for these seats to be respected? What does the act of always wanting to occupy a seat that apparently everyone can occupy reveal? Who is entitled to occupy a space?

The absurdity of having to ask (some of the participants) to leave those seats empty was the very reason for the necessity of the demand. The fact that was necessary to say: “Hey, remember we are in Zapatista territory, let’s be cool!” is problematic. The lack of awareness regarding this apparently practical or operative act reveals an inability to stop thinking about ourselves as individuals and not seeing the other as able to claim a space. The challenge is to get over the idea of our own individual comfort or wellbeing—to hold our wishes for a moment!—and it is a difficult one. It is indeed very comfortable to ignore questions and avoid working on what we can do better. The issue of the seats was a symptom; this apparently trivial incident reproduces attitudes and exposes those who rule bodies and spaces, and, in this case, decide how we occupy spaces in places to which we have been invited. It reveals the real power of the symbolic. Those empty seats are a metaphor that can be applied on a global scale: we need to refrain from occupying all the available space, and take care of the spaces we inhabit already.

Even if the Gathering was never labeled feminist, it was a meeting that invited all the women who strive. Besides the amazing historical and symbolical acheivement of having gathered all this diversity of bodies which think of themselves as “women who strive” from different practices, occupations and temporalities, the Gathering revealed the need to question one of the premises of feminism: “the personal is political.” What does “the personal” mean in that place? How could the reproduction of the logics of race and class privilege have appeared there?

As guests who mainly came from urban centers, our attitude was myopic. We failed to see the implications of certain basic and everyday stuff like the use of the toilet, the schedules for the meals, who required food, who prepared and who served it, or who picked up the trash. It is paradoxical that at a meeting of women, discussions and thoughts regarding invisible and reproductive labor—the unwaged work which among other quotidian tasks is attributed to feminized subjects (issues that have historically been part of this struggle)—were not practiced. The omission of these reflections reveals how far we stand from reaching a political coherence across these experiences.

At the Gathering, we thought that the way you deal with shit reveals your coherence or incoherence in all senses. The anecdote is telling: a certain number of latrines had been put at everyone’s disposal. On the second day, someone had literally crapped, and this happened several times. The problem was, that this/these person/s was/were incapable of cleaning up their own shit and leaving the toilet more or less in the same state as they had found it—it is so easy to play the fool! As a consequence, others had to take care of this shit. We realized that, for the time we were there, one of the most powerful aspects of the Zapatista stand was daily action. A kind of radical activism embedded in how we relate to the people we interact with every day, and the possibilities that can be triggered by these interactions.

The anticapitalist proposals of the Zapatistas mirror us: our urban buildings are products of capitalism, and, as such, the symptoms we have shared imply taking consciousness of other relations with the (female) body [cuerpa], and other understandings of the collective space. Cities are built according to the capitalist logic, which gives priority to the immediate present, and valorizes efficiency and productivity. Thus certain subjects, such as elder people and children become disposable. Conversely, to retrieve the past(s) from these presents, as for instance, in our attitudes towards old age, is important because it is a form of embracing different temporalities which potentially activate other pasts and presents, making certain other futures possible.

During our conversations we asked ourselves: which un/learnings of the symbolic bids of the Zapatistas can we translate into our cultural practices, and for what? We believe it is crucial to mention that they report situatedly on what it implies to reflect on themselves. Let us not forget that many of their strategies derive from their former status as army and the dislocation of what this means. For instance, their walking is not a rigid, military, erect walk, but it has other implications regarding rhythm, time and weight. When walking, they carry several bodies in the (female) body [cuerpa]: the baby they are nursing, the child they hold by the hand, the comrade they are waiting for, their own (female) body [cuerpa]. In this sense, this can be read as an intervention in the mechanisms of (re)presentation.

Their dwelling, or their specific presence evidenced the need to critically assess our presence in each of the different contexts. In our case, say, in the city: how can we acknowledge the different plural collectivities we inhabit? How do we translate them? How can we reflect on our mechanisms of (re)presentation in cultural practices, within the field of art, or in the forms of our protests?

In the Zapatista’s stance, we did not perceive the need to declare everything, to make absolutely all of their actions clear. It is so embodied, that they actually incarnate it, and this is how such porous and powerful images emerge from their most ordinary acts. It is important to underline that we are living a historic moment, in which a struggle is developing, for the possibility of other bodies and other experiences to be able to use (re)presentation and self-representation mechanisms/ devices/strategies/methods in different ways, without repeating practices such as taking the floor individually, or of everything the ego can tell and verbalize. This is why it is urgent to recognize and learn from the collective labor the Zapatistas have been carrying out to historicize and (re)present themselves.

They gave themselves the time to share their stories and to self-represent themselves through the version of each of the Caracoles. It was a performance in the diversity of stories and in the enablement of the complexity of the narratives in a heterogenous world. Even thought the presentation of the history of women within Zapatismo was a shared collective speech, each Caracol presented itself with their particular way of perceiving their participation.

It was not a resume on Zapatista women in a generic way, even if from our urban nearsightedness it was difficult to recognize this diversity. The shape of this temporality was also of listening. They spoke in Spanish because they had to, and have had to do it before. How could we have listened otherwise?

If we are standing in contexts such as this Gathering, it is imperative to inaugurate the possibilities in our (female) bodies [cuerpas] to speak non-hegemonic languages. What other type of dialogues could this enable?

We realized we lacked tools to transform our realities. It is necessary to create our own conditions to notice which other existential logics are possible. Maybe, here, the structures of non-hegemonic languages, the plasticity of artistic practice, or an interest in the sense of the forms and material uses of other/our everyday lives could enable the possibility to use these tools.

As subjects of an empire of the visual, we are in an era in which visualities are multiplying frantically. How can we put aside this order and enter our existence from other places and other senses? The Zapatista women give several possible answers: visuality is a fundamental part of their approach, as it encompasses from the way they dress and look to the way they occupy space. The use of the ski mask dislocates our gaze from the presence of and meeting with the other, inviting us to use our view from another place. We still look, but the focus is different. The ski mask is a metaphor that invites us to shift our gaze and thus the way in which we perceive our surroundings, for who looks and for who is looked at. Also the manner in which they stand or occupy space can be interpreted as forms of making presence which require more careful ways of seeing, forms that have non-Western cosmogonic implications and narratives on how the world is constructed.

By shifting this dislocation of visual hegemony to artistic/cultural practices, some of the questions that arise are: how can we trigger this type of encounters with our own means? How can these be tools for the construction of presents which are more coherent and better adapted to our stories, our affectivities and our expectations?

We are interested in the construction of metaphors and the radicality with which the (female) body [cuerpa] understands them. Therefore, we like to think of the Gathering as an obsidian mirror in which we can see our own shadows. If we think of 1968 and the failure of other social movements, what we saw at the Zapatista Gathering is the fact that we are still working outwards without reflecting on everything that we need to work on in ourselves. It is necessary to work on both aspects simultaneously: to solve our literal shit, metaphorically and collectively, and to solve the shit around us. It is a lesson in all aspects. Not only for those of us who were at the Gathering, but also for those who are listening to what we are transmitting. It is urgent. As guests on earth, we are not making it, and right now it is everyone’s concern to act for the common good. Of course, this urgency includes Art and its Artists. How are we acting? What are we reproducing? What is our responsibility with these societies? Which tools are we creating to survive in a less fucked-up way?

—

[1] Caracoles (literally “snails”) are places that host alternative forms of organization from within the villages that subscribed to the EZLN (Zapatista Army for National Liberation). The Caracoles function as points of convergence which integrate the construction of power through networks of autonomous villages and the integration of power entities such as self-governments. Most of all, caracoles are spaces occupied by the communities which built them. Because of this, they often include sports fields, schools, handicraft shops, food stores, canteens, kitchens, health centers, and other type of infrastructure to make communitarian life and political organization possible.

Comments

There are no coments available.