30.07.2018

Curator Alexia Tala gives a brief recap of the history of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, one of the most important symbols of resistance in Latin America.

Art and Freedom: An Introduction to Institutional Geopoetics

“The word utopia means no-place, no-time. But it also refers to a way

of dreaming of a better society, possible or not, that has to be found,

built. People can burn in the process, but it is impossible to take away

that ideal, that need.”

Ferreira Gullar in Mário Pedrosa 100 años [1]

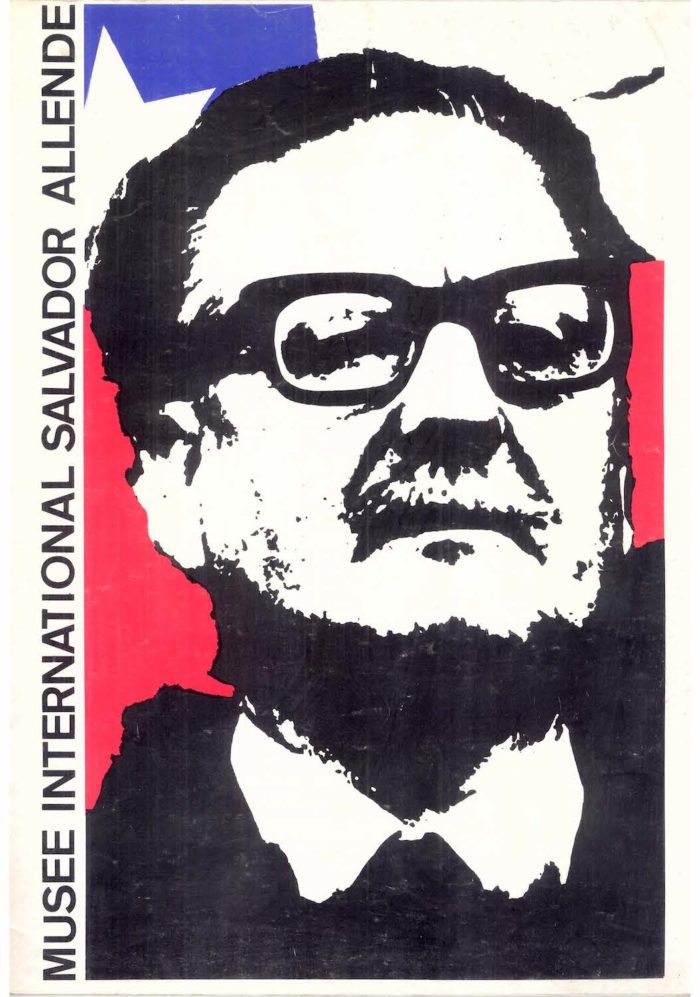

In May of 1972 a period of intense transatlantic correspondence between the members of the CISAC [2] (Comité Internacional de Solidaridad Artística con Chile, or the International Committee of Artistic Solidarity with Chile) and artists around the world began; it was through this correspondence that one of the main objectives of an important artistic endeavor crystallized. The letters contained details regarding the shipment of artworks from Chilean embassies of different American and European countries to Santiago. The 600 or so artworks were bound for the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Quinta Normal, and would be the foundation for the exhibition that would inaugurate the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA) in Santiago de Chile. That day was so full of excitement; between the speeches of the then-president Salvador Allende, Mário Pedrosa, and other official, Miguel Rojas Mix, director of the Instituto de Arte Latinoamericano, declared Pedrosa to be the great realizer of a dream: the construction of a museum that would host works donated by artists of the world in support of Chile and its socialist government. This was the first time the country had access to so many works by such great artists, all generously donated. This initial mood was fundamental for what the country and the museum were about to face.

One of the priorities of the Allende government was to reinforce access to culture—which they believed to be a right—so that intellectual and cultural activities would be accessible to a major part of the population, with the State taking on an organizational role. Because of this, Chile was enriched with diverse proposals in music, literature, and the visual and editorial arts, in an atmosphere in which artists could circulate their works among the Chilean people.

However, the success of this project was very soon thwarted by the political instability brought about by Pinochet’s coup, orchestrated with the help of Richard Nixon’s government. On September 11, 1973, the bombing of La Moneda brought an end to the first democratically elected socialist government in the history of Latin America. Allende’s death and the end of his government left the Museo de la Solidaridad without any support and it subsequently entered a state of total ambiguity and anonymity, a sort of holdover in time and space. In time, whenever a dictatorship is enforced, the future—which is ever uncertain—becomes blurred, replaced by a generalized uncertainty about what lies ahead and how long it will last. In space, the artworks were scattered, stored in various institutions in Chile and elsewhere, in embassies around the world, or stuck in custom offices in the process of being transported to Chile.

Although, as was expected, the cultural world went through a period of relative silence, generally known as el apagón cultural (the cultural blackout), after a while many artists felt the need to express themselves by means of clear acts of resistance in the form of “action-works” from different cultural fields. In the fields of literature, music, and the visual arts, collectivity appeared as the possibility to work with new creative dynamics and new channels of distribution, such as postal art, artists’ books, and a series of clandestine performative events. As words became dangerous, other kind of “images” began to circulate, most notoriously those of a multidisciplinary group called C.A.D.A. (Colectivo Acciones de Arte). [3] They worked in groups with participatory dynamics staging few but effective and conceptually powerful actions in public space defining art as a social and collective creative act.

This context explains why the existence of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende (MSSA) must be seen today as a great act of resistance, perhaps the major act of resistance any cultural institution has carried out in history. This act of resistance allowed for the creation of the CISAC. The initial idea of the MSSA came from José María Moreno Galván, who represented the committee in Spain, and it was Mário Pedrosa who implemented it, with Allende’s support. The project would probably not have gained enough strength without Pedrosa as the president of the CISAC. He was a very prestigious man, who had many contacts among his AICA colleagues (Asociación Internacional de Críticos de Arte), but, most importantly, his personality and conviction were key for the amazing speed and intensity with which the project was carried out, and for the poetic act of resistance that crossed geographical borders and reached the entire world in an ideological, social, and institutional balance.

Pedrosa used to say: “I will take this museum out of Chile, I will bring it to Mexico, and from then on it will be a traveling museum, a symbol of resistance. This museum was created for the people of Chile, for workers of the countryside and the city; I will not leave it to the military yoke. The museum will only return under a democratic regime.” [4] A few days after the military coup, Pedrosa secretly ordered the gathering together of the papers, documents, works, and pictures that had been kept safe in the house of Fine Arts director Nemesio Antúnez. Despite his intentions, the museum never left Chile. First of all, the artists reacted in different ways. I would go as far as to say that the shock of the coup, and therefore the timing of each of the donations, and the ensuing reaction of each of the members of the CISAC, had much to do with this. In 1975, a project called “Museos de la Resistencia” was implemented by those in exile, and involved the unfolding and articulation of networks of solidarity and the organization of multiple exhibitions of the artworks that had been donated by different countries. The exhibitions were kept as a sign of support to the Allendista government, and in expectation of a change that would allow the works to be integrated into the MSSA.

In the case of Spain, for example, the artworks had not yet been shipped to Chile. Moreno Galván, moved by what he thought of as a deep personal commitment to the project, organized various exhibitions at the Fundació Joan Miró in Barcelona in 1977, as well as in Madrid, Zaragoza, Palma de Mallorca, the Basque region, Málaga, and other places. The collection of Swedish works also traveled, notably to Spain, between 1978 and 1981. [5]

The United Kingdom’s donation is one of the special cases in the history of the museum. I myself was in charge of the study of Sir Roland Penrose’s archive, and had conversations with historian Guy Brett in the UK, who had also been invited by Pedrosa to work with the CISAC. In this case, the works had been exhibited in the Institute of Contemporary Arts in London during the months of July and August 1973 before they were donated. When the exhibition was over, the works were sent to the Chilean embassy. Their shipment was interrupted by the coup, and they remained stuck there under military custody. The British artists were very concerned about their works remaining in the hands of the regime. In March of 1974, after many failed attempts at communication, and after the exchange of many letters between Penrose, who was trying to retrieve the works, and the embassy, the artists finally received a positive answer. In this case—and this is merely my own conclusion—there was no act of resistance, since the shock of seeing the works in military hands only incited the artists to think of their quick retrieval. This immediate reaction was not linked to the value of each of the works, but to what this collective donation stood for symbolically and how problematic it would have been to leave it in the hands of a dictatorship.

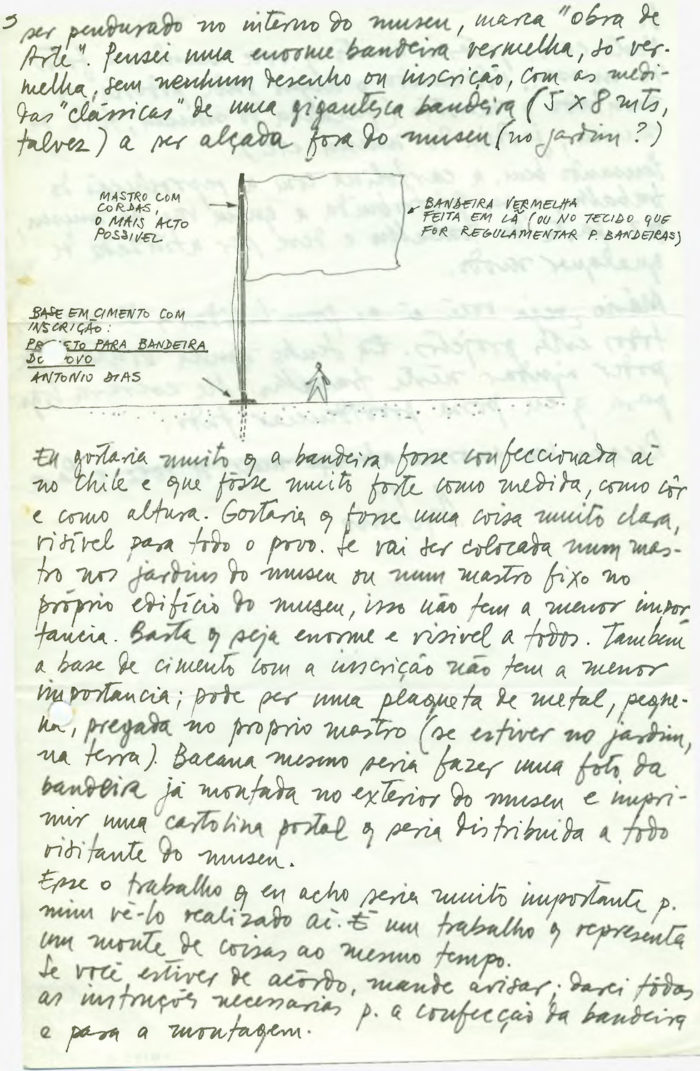

Many other things must have happened in different places, and these are still to be written in the history of the museum. Every bit of research reveals new facts, such as the initial phase of the research on the Brazilian donation, which I have carried out with Aracy Amaral. Our investigation led us to letters from Hélio Oiticica to his brother, confirming that there were a number of works that had arrived to the doors of the plane where they were then detained. Of these we know that some were returned to their creators, and that none of them arrived in Chile. Thus, all the works in the Brazilian donation which are now part of the collection were in fact acquired through the French shipment, since a major number of Brazilian artists lived there in exile.

It is necessary to underline the importance of the link between the configuration of networks of solidarity and the historical context. As regards the latter, the museum’s statute had already been shaped by the idea of the museum as project, empowering its political role and its contextual engagement according to the country’s specific situation. At the same time, it was founded upon the idea of transnational collaboration. The museum’s vocational territory extended its geographical limits. Moving away from traditional notion of the museum as a fixed institution, this nomadic and traveling project elicits thoughts on the potential of constructing a “geopoetics” beyond physical and political borders.

Geopoetics, a term coined by Kenneth White, refers to poetics as open dynamics of thought that seek to unite “thought on the Earth.” It understands geography from the perspective of nomadism—drifters— starting from the “plurality of contexts,” which composes it, as the diligent basis for its theoretical-practical manifestations. Geopoetics questions the idea of the nation, since the notion of territory is superimposed upon the Earth as a means of enforcing geographical borders. This allows one to think of the map as B. Fuller did: a hive of interconnections that shape it and give it life.

In the case of the museum, geopoetics allows for the idea of the museum as a project, disregarding borders and embracing the permanently changing political and artistic ideals which motivate it. Ideas that match with artistic communities in other places, as proved by the MSSA and the CISAC.

In recent years, the MSSA, headed by Claudia Zaldivar, has encouraged research on these networks of solidarity of donations, not necessarily with the intention of retrieving the artworks, but out of the profound need to reshape history, so that all these micro-histories can enrich and fill in the gaps. However, as a result of these investigations, forty-three artworks have been recently reacquired, which, upon their arrival in Chile among the socio-political tensions of 1973, had been relocated to the Museum of Fine Arts. Thirteen came from Switzerland, a shipment organized by Harald Szeeman; four came from the US, sent by Dore Ashton; one from France; fifteen from the Armando Zegrí Latin-American fund; and finally ten other works, which were only discovered to have been wrongly assigned to the Museum of Fine Arts in 2016. All these works feature in the MSSA’s most recent exhibition.

Understanding the Chilean military regime’s predisposition for brutal violence, and that many campaigns of civilian resistance were carried out in many parts of the world as part of the wave of liberating resistance that was sparked by the events of May 1968 in France and elsewhere, I dare say that this case has no match. Such a resistance on a socio-cultural level—across oceans, emerging systematically in different parts of the globe through different exhibitions in many different spaces and institutions, transforming the museum into a “space for freedom”—is a clear manifestation of the utopia that its creators imagined.

In those years, Mário Pedrosa claimed “art is an experimental exercise of freedom.” The international impact of this story is unparalleled. Artistic utopias, as we know, have shifted since Joseph Beuys, and social art practices tend to merge more and more into life. Undoubtedly, the efforts of all the people who made the existence of this museum possible, especially Mário Pedrosa during his years in Chile, were shaped by this will, which would bring us to understand the museum as a huge work of art, built on geopoetics and implemented by this warrior, who certainly managed to unite art and freedom.

*This text is based on another, longer text by the same author, titled Mário Pedrosa: “guerrero del arte y la libertad.”

**Traslation to English by Ambar Geerts

–

[1] Ferreira, Gullar “Entre Sócrates e Dionisio,” in Aracy Amaral, Mário Pedrosa 100 años (São Paulo: Fundaçao Memorial da América Latina, 2000), 25

[2] The CISAC was formed by Rafael Alberti, Louis Aragón, Giulio Carlo Argan, Dore Ashton, Carlo Levi, Jean Leymarie, José María Moreno Galván, Aldo Pellegrini, Mariano Rodríguez, Julio Starzysky, Harald Szeemann, and Edward de Wilde. Mário Pedrosa invited Guy Brett to join the committee, but his participation was not related to the donations, but to the acts of resistance.

[3] The C.A.D.A was created by visual artists Lotty Rosenfeld and Juan Castillo, poet Raúl Zurita, sociologist Fernando Balcells, and writer Diamela Eltit. It was active from 1979 until 1985.

[4] Daisy Peccinini, “O Museu de la Solidaridad con Chile,” in Aracy Amaral, Mário Pedrosa 100 años, (São Paulo: Fundaçao Memorial da América Latina, 2000), 23.

[5] Aracy Aramal, Mário Pedrosa: Um homem sem preço en Textos do Trópico de Capricórnio – Artigos e ensaios (1980-2005) Vol. 2: Circuitos de arte na América Latina e no Brasil (São Paulo: Editorial 34), 98.

Comments

There are no coments available.