Lorena Tabares, co-editor of this issue, recaps ten performances that took place in Mexico between the 1990s and the first decade 2000s.

10 Performances in Mexico Millennials Didn’t Get to See

Continuing with the 1st part published last week, here is the 2nd release of the recount.

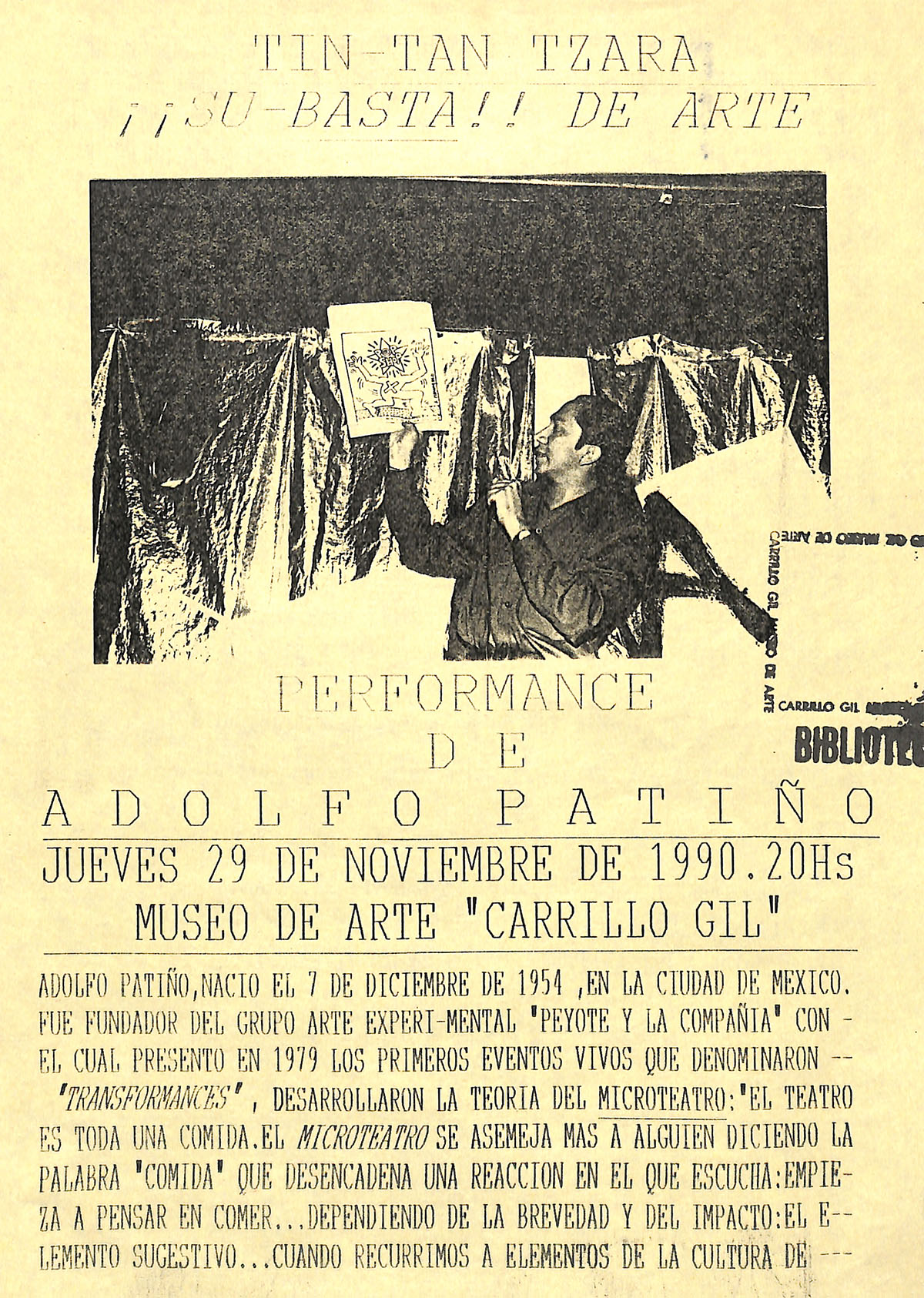

Days of Performance at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil

Collective Week of Performances

November 21, 22, 27, 28, and 29, 1990

Museo de Arte Carillo Gil (MACG), Distrito Federal

Under the direction of Sylvia Pandolfi, the Days of Performance organized at the Museo de Arte Carrillo Gil were an antecedent of the conception of a narrative about performance and its dialogue with institutional spaces. This event brought together a new audience along with a group of performers, writers, and interested people, who came from a prolific underground, alternative art scene that was built up from the margins and out of a spirit of independence.

Throughout that week, the following performances were presented: On November 21, the opening day, Roberto Escobar presented La cruxada de los niños, primer acto; on Thursday the 22nd, there were two performances, Usuarios y operarios’s El planeta bizarro, and Produkto MS’s Tv Philco Mod. 4407; the following day, three actions were carried out, Melquiades Herrera’s Libertad de expresión, and Maris Bustamante’s Durante el congreso and El sexykitsch a chaleco; Wednesday the 28th saw Geografía humana by Los escombros de la ruptura, and Felipe Ehrenberg’s Condición códice; on November 29, the last day at the MACG, Adolfo Patiño and Justino Balderas presented Introducción Poemas abstractos con Hugo Ball y Su-basta! de arte con Tin Tan Tzara, César Martínez showed What’s Happening?, and Proceso Pentágono with Venta de garage [10].

From this week of activities only loose sheets of El maquinazo—a newsletter about the performances that took place—remain. Cuauhtémoc Medina, the museum’s head of research, was one of the editors of said newsletter; his explanatory texts as derivatives on performance, elaborated on the relationship with avant-garde and modern art. In addition to the texts by Medina, the publication contained an editorial section and correspondent texts by Pablo Picatto and Renato González Mello, who also chronicled the art actions that took place in the museum’s basement.

For the museum it was somewhat different; it modified the experience of the regular public and attracted a fresh, much younger audience. As for the realization of El maquinazo—it opened up a field of experimentation concerning the documentary record and performance literature, since this was an artisanal proposal whose contents were made at the limit of the act itself.

Mónica Mayer and Victor Lerma

Balcony of the CENIDIAP, May 24, 1997

Centro Nacional de las Artes (CNA), Distrito Federal

In 1997, Mónica Mayer and Víctor Lerma proposed a “crossed” action-ritual within the framework of the Salón Anual de Artes Visuales held at the Centro Nacional de las Artes. Their goal was to raise questions about the situation of documentary memory of the ephemeral practices and non-objectualisms in Mexico, and about the obligations of the National Center of Research, Documentation, and Visual Arts Information (CENIDIAP), located in the same facilities where the action took place.

In Mexico, documentation of ephemeral actions is almost nonexistent, which has led to a lack of knowledge about and unawareness of many art productions among the younger generations, as well as to visual and testimonial gaps in art historical narratives. In referring to the CENIDIAP [11], the institution responsible for housing the documentary patrimony of contemporary art practices, the artists signal the topic and combine it with a ritual and a magical experience in its facilities, presenting an unfolding of the layers implied in the making of an action and documenting it as a residual outcome. The action involved Luis Rius Caso (CENIDIAP director) and researchers Edwina Moreno, Graciela Schmilchuk, and Cristina Híjar.

On Wednesday the 14th, the artists read a text about the problems of documentation of non-objectualisms at the CENIDIAP, and solicited signatures from the audience to endorse the suggestions that the problems sought to work through. In light of limiting regulations, they attended a cleanse that began the previous night with the help of a professional and of Angelina Vásquez. The following day, between reading and action, they used the altar—with coconuts, incense, wine, flowers, candles—and invited the audience to make amulets.

This action—that directs the gaze in the direction of the documentation and recording of actions as a fundamental and disciplinary link, and a magical and popular action—reminds us that in order to see change in the institutional realm, it is necessary to have a lot of faith.

Paricutín, Acciones in Situ

Performance Encounter curated by Hortensia Ramírez and Víctor Martínez

November 23 to 30, 2000, Michoacán

The performance encounter Paricutín, acciones in situ [Paricutín, In Situ Actions] was an exploration through four different paths of the landscape surrounded by the Paricutín volcano. This landscape, a challenge for the aesthetic experience and the construction of an action, demanded that the participants get rid of almost all their belongings, in order “to put the body forth,” [12] and go into and reconnect with the environment.

This project started with research and curation by Hortensia Ramírez and Víctor Martínez, and took shape with the participation of Mexican artists Roberto de la Torre, Mirna Manrique, Pablo Casacuevas, Ignacio Granados, Sakino, Katia Tirado, Yvan Herrrera, Hortensia, and Víctor. The guest foreign artists were Iwan Wijono, Sonia Renard, Eva Vadja, Gusztav Üto, and Volker Schoenwart. The documentation of the project was done by Víctor Jaramillo Cruz, Jorge López, and Jorge Luis Sáenz, who made a complete report, and Janice Alba in production.

The group visited the ruins of San Juan Parangaricutiro’s church, a site where a baroque church was trapped in hardened lava. Then they went to Malpaís or mar de lava, a zone that today has an extension of more than 15 thousand meters of volcanic stone. The third expedition was to Patzácata or the Angahuan forest reserve, a forest area. They finished at the crater of the volcano, which is inactive, but still exhales heat and steam.

Among the performed actions, Mirna and Ignacio inflated balloons in the shapes of dolphins and whales and placed them throughout the landscape and Mirna, wearing an floater read the story that begins: San Lázaro, el caballo flaco, el mar de lava y el volcán sin gaviotas [San Lázaro, the skinny horse, the sea of lava, and the volcano without seagulls]. Roberto de la Torre executed Chemical Lava/erupciones de bolsillo, in which he simulated a lava eruption coming from his and the other collaborator’s joined hands, while being recorded near the peak of the volcano. On the other hand, in his performance La flor vs. gladiador, Víctor became a quadruped that ascended the rocks, blindfolded, relying exclusively on his sense of touch.

Out of this project emerged approximately fifty works, including actions, videos [13], texts, and a large quantity of photographic materials as modes of understanding in situ actions.

Katia Tirado

Totemismo I [Totemism I], 1998

Totemismo II [Totemism II], 2000

Art Deposit and the Museo de la Ciudad de México, Distrito Federal

In 1998, Ulises Mora invited Katia Tirado to be a part of 6 comportamientos, a curatorial project with an interest in the female side of the Mexican action art scene that would be explored through six searches and diametrical characters [14].

For Katia, Totemismo I came with a question, how will I present myself to the world? The artist built a column with her body, soft and flexible, supported by a gas tank, rigid and threatening. Her hair, connected to a bridge which united two parts of the house, appeared as an antenna from which Katia could perceive the vibrations of visitors walking on her head. The precarity of her act invokes the state of convulsion and affectation that takes place when establishing relationships with others, as well as a metaphor about the head-rooftop. The moment of tension occurred as she slowly began to cut the threads that held each of her dreadlocks.

Totemism is the search for symbolic power, of being present, self-representational, and self-referential. “I want to withdraw in order to seek those protective allies from within, in my thoughts”, says the artist. For her, that head-rooftop is the place where her thoughts reside; it is that space where the metaphysical and physical planes come together, and it is not clean. This is how she presents her psyche as the telluric, dark, and painful space of relationships, of individual thoughts, of one’s own words and those of others, which push us to cons- constantly ask ourselves: Who am I?

In 2000, Katia performed Totemismo II as part of the exhibition Señales de resistencia, curated by Lorena Wolffer. Building once again on the idea of herself as totem, she cut and abandoned her hair, liberating herself from her bonds.

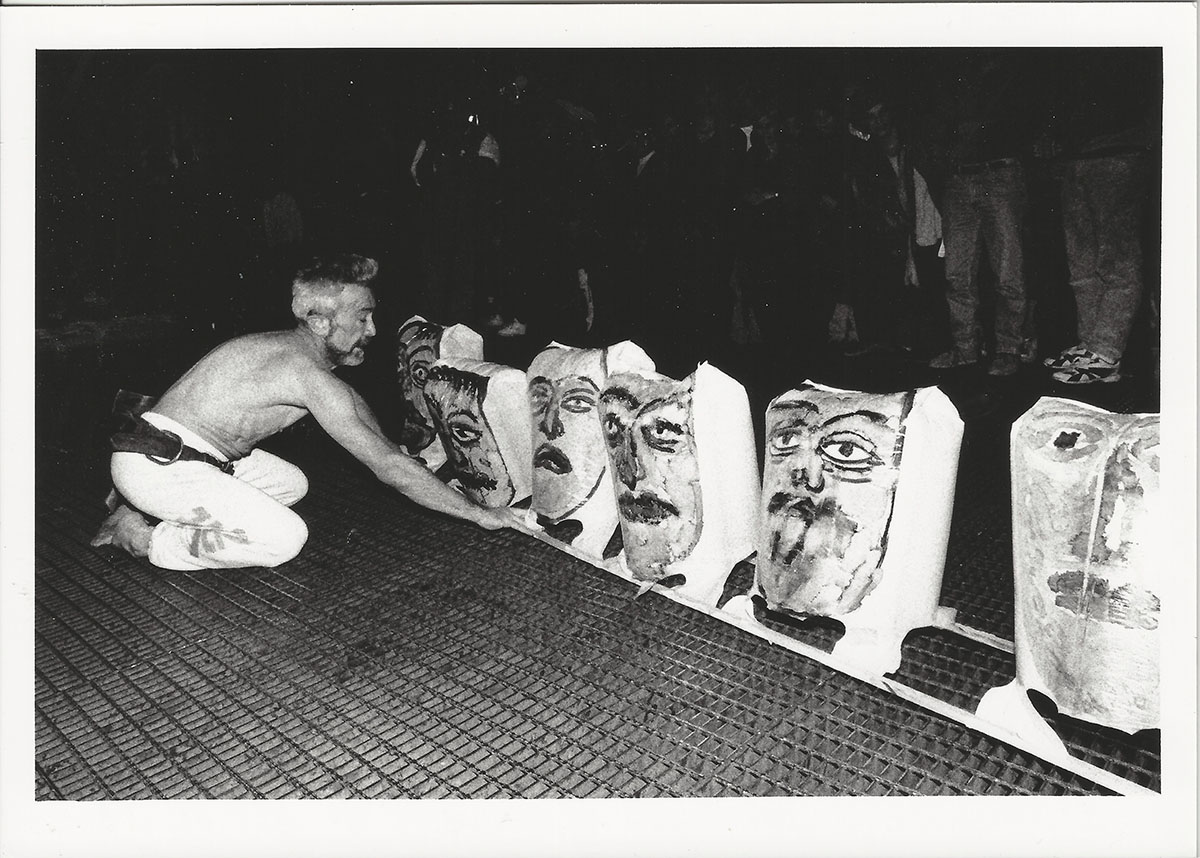

Marcos Kurtycz

La serpiente del metro [The Serpent of the Metro], 1995

4th International Performance Festival

Zócalo of Mexico City, Distrito Federal

In 1995, Marco Kurtycz [15] participated in the 4th International Performance Festival of the museum Ex Teresa Arte Alternativo [16] with one of his latest works dedicated to the people of the city: La serpiente del metro. In this performance, acting in that open, saturated with pedestrians and curious people, reiterated his own street consciousness, that which he had been addressing for twenty years.

Marcos began with a mask on his face, holding a rectangular and long artifact behind his back. Dressed in his habitual white uniform, with his ax at his waist, and a pair of boots to which he tied a pair of horns that sounded with each of his steps, he walked through the Zócalo until he arrived at a subway vent. He unloaded the heavy artifact, took off his shirt and shoes, and began to walk across the vent on his knees [17].

Again, he searches for his artifact, unwraps it, and tries to get it to remain stable on top of the vent emitting hot air. The wooden device with plastic bags and painted faces inflates as a witness of the invisible serpent.

In the same year, 1995, Kurtycz presented an installation of rectangular faces, bidimensional works in which he makes a list of all the times this animal is mentioned in the Bible. His fascination with ritual, a space present in culture, equals his fascination with serpents. And there he was like a translator of contemporary, syncretic symbols into actions, into performances.

Comments

There are no coments available.