Reports - Bienal de Arte Paiz Guatemala - Guatemala Latinoamérica

Reading time: 9 minutes

23.11.2023

In the context of the celebration of the XXIII Bienal de arte Paiz in Guatemala, we invited the independent curator Jaime González Solis to write in relation to the link between art and politics within one of the most important biennials in our region.

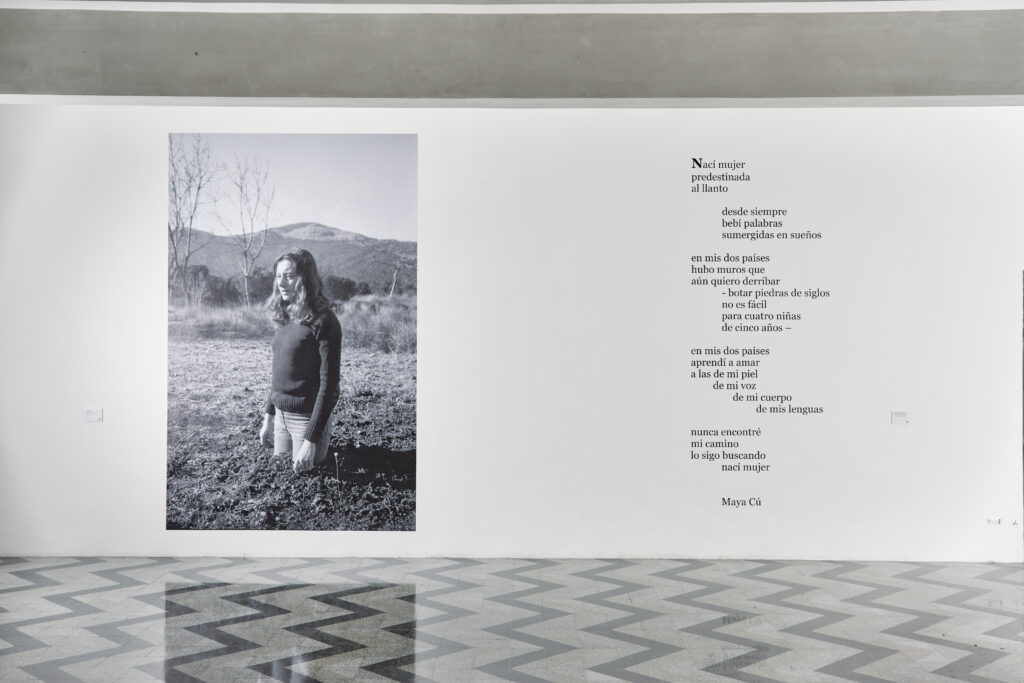

The Paiz Art Biennial has been a central part of the contemporary art ecosystem in Guatemala since its inception 45 years ago. Its operation has promoted changes in the artistic languages of Guatemala, accompanying the cultural field in the turbulent evolution of the political and social history of recent decades. The evocative title of its most recent edition, I drank words immersed in dreams, is part of the poem I was born a woman by Maya Cu, a referential voice of contemporary Mayan poetry. For curators Juan Canela and Francine Birbragher-Rozencwaig, this verse evokes the concepts of language, body and territory, whose reflection was pivotal to the curatorship. The biennial proposed to address these ideas from a feminist and intersectional enunciation to influence the hegemonic narratives of art, which are primarily masculine and Western. In this sense, the approach of this edition focused mainly on works by women, gender dissidents, indigenous people and Afro-descendants. On the other hand, convening historically marginalized voices also focused its topics and approaches on the recovery of memory and the critique of the present for the “imagination of common futures.”

The curators formed a curatorial assembly that dissolved the univocal voice of the curatorship to include that of the artists. Minia Biabiany, Marilyn Boror Bor, Duen Neka’hen Sacchi and Juana Valdes, in addition to contributing pieces to the biennial, participated in the discussions that shaped its approaches. The edition included, by invitation and open call, the work of a total of 30 artists and groups from Guatemala, the Caribbean and Latin America. In order to problematize its themes and the exhibition model, the Shared Knowledge program, curated by Esperanza de Leon, gained importance, since it articulated a series of pedagogical activities in various formats that expanded the reflections of the artistic projects for a period longer than that of their exhibition.

The biennial was held in five venues: the Centro Cultural de España, the Centro Cultural Municipal Alvaro Arzu Irigoyen and the Portal de la Sexta in Guatemala City; as well as the Centro de Formacion de la Cooperacion Española and La Nueva Fabrica, located in Antigua Guatemala. Each space articulated the works based on concepts derived from the initial reflection: the power of orality, divergent writings, links with nature, the territorial logic of landscape, or the idea of community, were recurring themes in these groups and nuclei of the biennale

At the headquarters of the Centro Cultural de España, critiques of the dynamics that perpetrate systems of violence were included. The Kaqchikel Mayan artist, Marilyn Boror Bor, denounces the impact of the San Gabriel cement factory on the community of San Juan Sacatepequez in her project They took away the mountain, they gave us cement (2023), which presents paintings, textiles and ceramics from the community covered, broken or imprisoned by concrete. In the work of Martin Wannam, the wound of discrimination is made present through the video of a performance in which the artist, standing in front of the National Palace of Guatemala, has the insulting word hueco (“hollow”), used to refer disparagingly to homosexuals, carved on his skin with a scalpel. . For his part, Eliazar Ortiz Roa reflects on cultural and economic exchanges in markets on the Dominican-Haitian border, addressing the violence exerted on their natural landscapes in an installation created with materials, techniques and languages specific to the area.

The written word, its powers, as well as the notion of shelter as a symbol of intimate protection, articulated some of the practices displayed at the Centro Cultural Municipal Alvaro Arzu Irigoyen. The installation They eat poems drenched in milk, one two three cats (2022) by Carolina Alvarado connects the Mayan worldview of the Popol Vuh with contemporary poetry to honor the lives of seven poets and writers murdered during the armed conflict in Guatemala. Duen Neka’hen Sacchi creates shelters for family objects and memories from Argentina, intimately crossed by the trauma of violence and terror present in their nightmares. Risseth Yangüez Singh opens up her experience as a black woman in Panama from how it intersects with the way she herself and others relate to their hair. In Make me a cocoon (2023), Yangüez records on video the intimate 72-hour process in which she built a shelter for herself with hair extensions with the help of those closest to her.

At the Portal de la Sexta, productions were brought together that reconcile the use of ancestral and modern technologies to imagine sustainable systems. The participatory work of Sallisa Rosa—originally from Brazil and who experiments with direct work with specific groups—is based on the work of corn planters in the community of El Tejar. As a result, they jointly generated a mural that records on clay tablets the hands of these workers of different ages, along with their corn ears, to account for the symbolic value of corn and the work of planting and harvesting, which are, in essence, collaborative practices. For its part, the La Nueva Cultura Material collective, made up of Valeria Leiva and Bryan Castro, presented a living mural made from the mycelium of the Pleurotus Ostreatus fungus to imagine, using materials created with biotechnology, developments of more environmentally sustainable systems.

Dreams as a theme are addressed at the Centro de Formacion de la Cooperacion Española. The project by the Tz’aqaat collective, made up of Cheen (Cortez) and Manuel Chavajay, is based on the narration of five different dreams that involve reflections on ancestral knowledge and premonitions of the future of the turbulent world we inhabit. Each of these dreams was materially interpreted in multiple formats: from installation, embroidery, sculptural intervention, to video performance. For his part, Itziar Okariz presents the record of his dreams in formats that experiment with the typographic formation and appearance of his words on paper to generate concrete poems that link us with those dreamed discoveries and the estrangement they generate. Minia Biabiany explores the repercussions of colonial thinking on the perception of territories in the installation Listen to the ash (2023), which also connects the volcanic territories of her native Guadeloupe with Guatemala.

On the other hand, weaving as an ancestral and metaphorical reference was a recurring technique in the pieces at the biennial. In Julieth Morales’ work, she links up with the anacos or skirts, which are characteristic of the Misak territory in Colombia, whose different threads and colors represent areas of the territory. For her part, Zoila Andrea Coc-Chang uses it as a discursive possibility to weave together Asian and American contexts from economic exchange and cultural transits, recorded in food remains, organic material and wrappings.

The biennial took as its starting point the practice of Margarita Azurdia, Ana Mendieta, Fina Miralles, Maria Thereza Negreiros and Cecilia Vicuña, leading artists of the sixties and seventies. At the La Nueva Fabrica venue, their explorations on the oral and written word, as well as interventions on the landscape and nature, were shown. These practices influence the stories and genealogies of the history of art from these decades. When assembled, they activate dialogues and provide a conceptual framework for the entire biennial. The “rupestrian” sculptures and silhouettes that link Mendieta’s body with the landscape of Jaruco, in Cuba, or the powerful image in which Fina Miralles buries her legs in the ground to become the tree-woman (1973), among other referential works, detonated imaginaries, in which the curatorship found gestures that link the practice of new generations. An example is the corporal and performative assimilation of bird songs by Laia Estruch, or the speculation on female archetypes in the Mayan worldview in the video The force that emancipates the body (2022) by the Ixq’Crear collective.

The languages of this edition are part of a general interest in art to face a future that is increasingly difficult to imagine. Perhaps the greatest contribution of this edition was drawing a map that records how, in sensitive terrain, climatic, political and social emergencies in Central America are coded. Furthermore, this contribution has the particularity of doing so from the perspective of marginalized communities, whose territories in the region share cultural affinities derived from their multiethnic pasts, colonial legacies, and recent violent pasts. On the other hand, the selection of artists also allows us to see an intense variety of artistic initiatives that are expressed from multiple trenches and resistances, generating a living network of involvement with contemporaneity.

At the same time as the biennial opened its doors to the public, the ruling party’s illegal efforts to block the opposition party’s opportunities in Guatemala’s electoral process generated tension and uncertainty in the public sphere. The arrival of the only party with a strong anti-corruption stance to the second round of the election was perceived among Guatemalans as a possibility of change in the future. In what way can the approaches that were displayed within the rooms be linked to that right to the future that was demanded at this time in the social field?

Even at the time this text is being written, the complex electoral process continues in an intense and intricate development. The efforts of the so-called “corruption pact” continue to illegally oppose the decision that Guatemalans made at the polls. These efforts by the public ministry with its general minister have been vigorously confronted in recent days by civil society, led by representatives of indigenous peoples. Despite having been historically silenced in political representation processes, it is the indigenous people who have been at the forefront of peaceful demonstrations and organizing a series of blockades that articulate a national strike to protest against the arbitrariness and tyranny of the State. In this sense, it becomes even clearer why the enunciation and sensitivity of those who represent at least 50% of the country’s population must be understood and heard at multiple levels. In addition to the contributions to the field of the “sensitive” and addressing the link with multiple spiritualities and their vision of the world, it is worth asking how an artistic institution can connect with the discourses it presents beyond art. The curatorial display of the twenty-third edition of the Paiz Art Biennial unleashes multiple questions about how to intertwine this poetic enunciation with a future that, despite the efforts of recent years and the achievements of civil mobilization in Guatemala in the face of the reiteration of corruption and impunity, we continue to see it unraveling before our eyes.

[1] Rosina Cazali, “The State of the Situation”, at the XIX Paiz Art Biennial. Transvisible (Guatemala: Paiz Art Foundation, 2014), 19.

[2] Curatorial text in: XXIII Paiz Art Biennial. I drank words immersed in dreams (Guatemala: Paiz Art Foundation, 2023).

[3] The Shared Knowledge program started on March 30, 2023, three months before the inauguration, and was extended until July 30. The exhibition at the five venues could only be visited for two weeks, from July 15 to 30, although its opening was extended at the La Nueva Fabrica and Centro Cultural de España venues until September 30 in the #BienalExtendida program.

23.03.2024

Opinion Cartografía sentimental de la brutalización en curso Argentina, Latinoamérica

Duen Sacchi

22.03.2024

Marginalia

(Español) La Revuelta

08.03.2024

Opinion

María Galindo

Comments

There are no coments available.