04.08.2016

by Natalia Valencia, Santa Fe, New Mexico, USA

July 1, 2016 – January 31, 2017

MUCH WIDER THAN A LINE

SITELINES SANTA FE 2016

Curated by Rocío Aranda-Alvarado, Kathleen Ash-Milby, Pip Day, Pablo León de la Barra and Kiki Mazzucchelli

“Brighter than several suns at midday” was how Manhattan Project nuclear program director General Leslie Groves described the impact of the first controlled nuclear test in history, 1945’s “Operation Trinity,” which the US government conducted in secret at Alamogordo, New Mexico. At the time, the area was inhabited by nineteen Pueblo, two Apache and part of a Navajo nation.(1) The historical episode—that certain scientists consider the beginning of the Anthropocene(2)—is referred to in the curatorial research supporting the SITElines Santa Fe 2016 Biennial. Beyond the geological nomenclature—the scientific community has yet to agree entirely with regard to its beginning—Groves’s description interests me because of its (unintentional) poetic potential.

In concrete terms, those concentrated suns that exploded over Alamogordo more than seventy years ago produced radiation that to this day affects the health of the area’s original, indigenous people. Often they lack the means to acquire needed treatment in the United States healthcare system(3) Updated historical accounts about the Trinity Project on the US Department of Energy website state the location was chosen for “its remoteness.”(4) It brings to mind Naomi Klein and her conference “Let Them Drown: The Violence of Othering in a Warming World,” presented in 2016 on the anniversary of Edward Said’s death. In it, she describes the recognition of the life of the Other—the non-white and non-Western—as less important, as well as the long-standing Western custom of using the Other as guinea pigs.(5)

So what on the symbolic plane might evoke that figure of several suns’ force, all shining at the same time? If language is the vehicle through which science is crossed, and mixed, with poetry, how can we use language to negotiate our relationship with the land, the non-human and the inhuman?

SITElines Santa Fe 2016 emphasizes the importance of non-Western knowledge in the Americas (assuming the heterogeneity that such a focus implies) and therefore opens up perspectives to other ways of naming the world. In her text for the biennial’s catalogue, co-curator Pip Day suggests that when the Inuit say the earth is wobbling, their use of language is not metaphorical. On the other hand, and indeed metaphorically, what ought to wobble and spin on its axis is Western understanding of other cultural interpretations of ecological phenomena, in order to preserve life on Earth. SITElines organization Managing Curator (who is not curator of this latest biennial) Candice Hopkins, a member of the indigenous Carcross/Tagish nation, from the Canadian Yukon, opened the event with a specific protocol: thanking above all the Native custodians of the lands that surrounded us there, the ancestors; then she called out each participating artist by name.

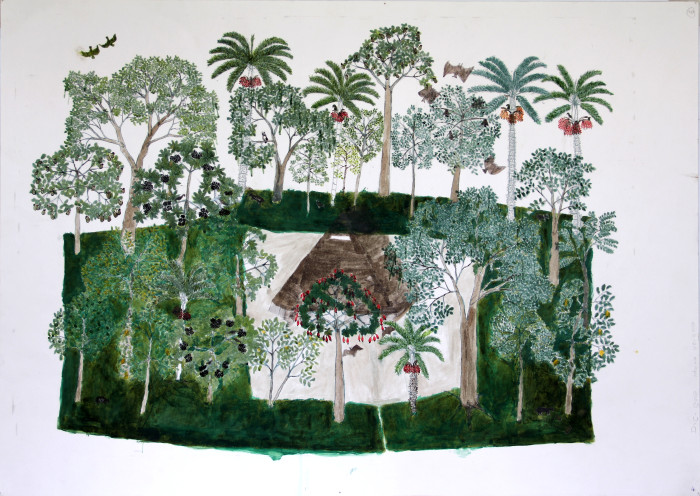

As we made our way around the biennial, we did indeed discover diverse, wide-ranging contemporary production on the part of artists from all over the Americas, several of whom identify as indigenous or of indigenous ancestry. They ranged from Inuit director Zacharias Kunuk’s magnificent film Atanarjuat: The Fast Runner (2001)—which portrays the Arctic’s traditional ways of life and cosmogonies—to Maria Hupfield’s performance-based research on the vernacular materials and forms with which the body adapts to the environment, in It Is Never Just About Sustenance or Pleasure (2016); Raven Chacón’s poetic educational project, undertaken with the Native-American Composers Apprenticeship Project in Arizona, in which the sound artist teaches young Native-American composers to unlearn the string quartet’s possibilities; or Abel Rodríguez, a Nonuya and Muinane indigenous “plant connoisseur” born in the Colombian Amazon’s La Chorrera, whose drawings recreate seasonal cycles in his native land’s topographies, a reflection of his ancestral land-stewardship knowledge.

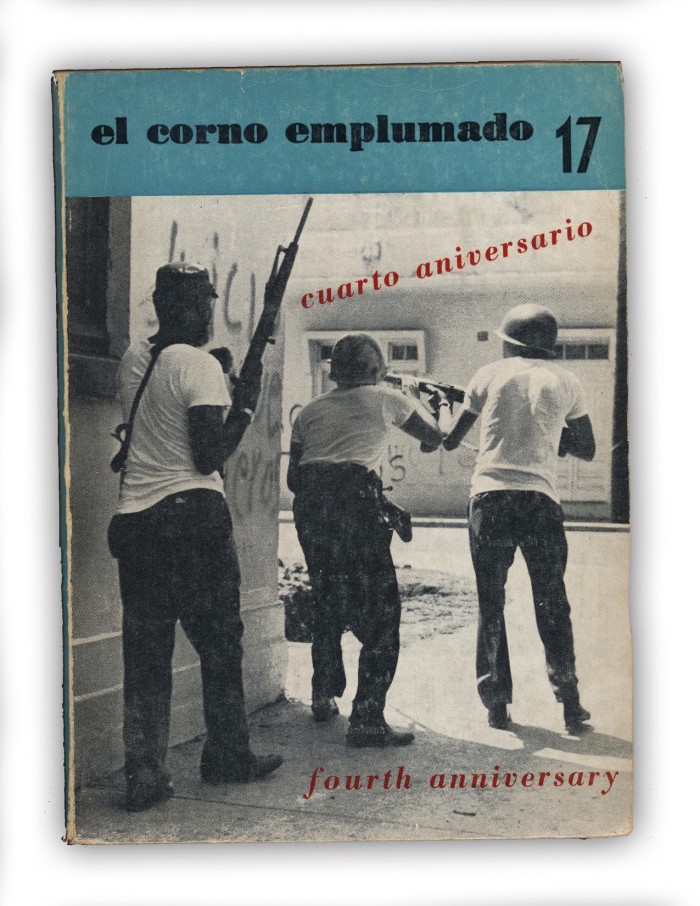

Mixed in with those pieces we happened on historical figures whose prolific work still offers true archival gems to curators, as is the case with Marta Minujin, David Lamelas, Cildo Meireles, Lina Bo Bardi, Graciela Iturbide, Miguel Gandert, Pierre Verger and particularly Margaret Randall, with her fantastic documentation of the independent publication El Corno Emplumado, which she edited in Mexico alongside Sergio Mondragón in the 1960s.

How, therefore, do all these pieces dialogue? If what divides or connects them is much wider than a line, then it may be worthwhile to consider which works all but exclusively belong to the contemporary art realm and which more widely speak of culture.

It’s also important to consider that tiresome but recurring question: who speaks for the Other, and from what place? On display are impressive photographs of entranced Candomblé practitioners from 1950s-era Brazil by the French photographer and self-taught ethnographer Pierre Verger. Also present are Graciela Iturbide’s iconic photos of the indigenous Seri people of Sonora that Mexico’s Instituto Nacional Indigenista commissioned in the 1970s. In both cases, curators leading gallery visits stressed that both Verger and Iturbide had achieved a degree of integration with their portrayed subjects that positioned them somewhere beyond the simple colonialist figure of the artist as ethnographer (as “evidenced” by a photo portrait of Iturbide’s face painted identically to those of her indigenous companions). This assertion is inherently problematic as it alludes to colonial representation schemes that don’t seem to have been overcome completely.

More significantly, one of the exhibition’s principal unifying themes is the archive of the Paolo Soleri Amphitheater, an experimental architectural project Santa Fe’s Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA)—and its visionary founder, Cherokee designer Lloyd Kiva New—commissioned in 1964. The amphitheater mixes regional, vernacular architectural elements with those from classical theatre; it incorporates a biomorphic stage that affords multiple perspectives (as opposed to Western theatre’s sole vantage point) as well as other interesting hybridizations. In their day, these served to complement the equally experimental program of Indian Theater and performing arts that were taught and staged there during the Institute’s “golden era,” a progressive mix of tradition and utopian thinking. Sadly, after the IAIA moved off the Santa Fe Indian School campus, the amphitheater fell into disuse and today stands all but ruined due to prohibitively high maintenance costs. For the installation in the space of the biennial, the curators invited architect Conrad Skinner to show documentation of the history of the amphitheater and indigenous Pueblo artist Eliza Naranjo Morse to create a sculpture in collaboration with her mother –in order to account for two points of view regarding the amphitheater’s symbolism as an arena for discussion. But for some reason, the catalog only documented Skinner’s point of view and Naranjo is virtually eliminated from the publication. In his text, Skinner mentions merely that “New Mexico’s indigenous Pueblos were opposed to the project for twenty years,” yet fails to say why. He then goes on to accuse the campus’s current Native American administrators of refusing to restore the structure. Why is there but one (white man’s) voice recounting this history? The public has no access to written indigenous perspectives on the project nor their evolution over time. The building’s historical importance is perfectly clear and this exercise in visibility attests to impeccable curatorial work, but discussions regarding conservation might better be left as questions rather than passive accusations. What would happen if—instead of clinging to materiality—our Western memory were content to archive memories of the Soleri Amphitheater orally? Would it then cease to be Western?

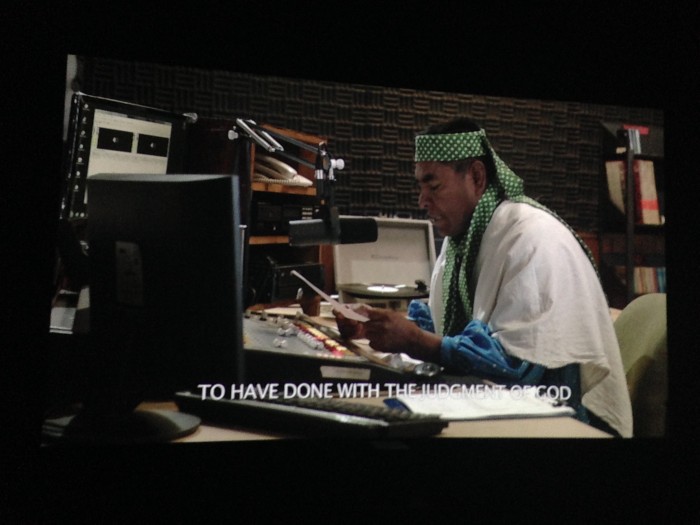

In his film To Have Done with the Judgment of God, commissioned by the biennale, Javier Téllez’s use of language is open to interpretive ambiguity, an outcome of his long investigation into the concept of madness in the West. He commissioned a Rarámuri (Tarahumara)-language translation of the French radio-play Pour en finir avec le jugement de Dieu, written by surrealist playwright Antonin Artaud in a French mental institution in 1947 and which was censored as obscenity in its day. Its text speaks of a journey Artaud made through the Sierra Tarahumara a decade earlier as well as his participation in a peyote ceremony. The play is loaded with hallucinatory, visceral figures and observations on religion and the human condition that attest to a collapsed rationality. In conjunction with local station Radio Xetar, Téllez broadcast the recording throughout the Sierra Tarahumara region in December 2015. The film shows the instant the recording was transmitted, in households and other everyday settings; we see indigenous people grinding corn and performing other daily tasks, nonplussed by the delirium that floats out of the radio. Other scenes recreate Artaud’s travels through the Sierra, past the anthropomorphic rocks at Valle de los Monjes, ending up at a real-life peyote ceremony. Téllez here walks on thin ice, as the staging of these situations implies, again, an instrumentalization of the Other and confronting the great problems of the colonial anthropological gaze from the XIX century to this day. However, his excuse to navigate through these sensitive questions is madness itself, which is supposed to neutralize morality in this case. By negating the white spectator who does not speak Rarámuri (there are no subtitles to the translation of Artaud’s text), meaning is somehow suspended for the Western audience in a gesture at once jocular and demented that reconfigures rationality’s limits. How does a mad man name the world? And who are the true crazies?

Notes:

(1) https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/trinity_evaluations.htm. Last consultation 20 July 2016.

(2) http://news.berkeley.edu/2015/01/16/was-first-nuclear-test-dawn-of-new-human-dominated-epoch-the-anthropocene/

(3) To learn more about the as-yet unresolved issue of Trinity-Project-victim reparations: http://indiancountrytodaymedianetwork.com/2014/03/05/guinea-pigs-indigenous-people-suffering-decades-after-new-mexico-h-bomb-testing-153856?page=0%2C0

(4) https://www.osti.gov/opennet/manhattan-project-history/Events/1945/trinity.htm. Last consultation, 26 July 2016.

(5) http://www.lrb.co.uk/v38/n11/naomi-klein/let-them-drown

Comments

There are no coments available.