13.11.2023

Curator and independent researcher Manuel Vásquez-Ortega writes about the work of Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe; Yanomami artist from the territory occupied by Venezuela.

The idea that what is dead cannot be named seems impossible to affirm in a world understood through Western epistemological constructions, recurrently referential to the past, and elaborated over centuries of written, rationalized and shared history under a series of progressive parameters that allow us to understand our time and the chronological ways of existing in it. However, in a reality that runs parallel to our existence, other forms of us can state the premise that introduces us, and thus carry the weight of what the impossibility of naming what has perished implies.

Hence, following the ancestral convictions and beliefs of the Yanomami groups settled in the Venezuelan Upper Orinoco, the indigenous artist Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe affirms that “only what is alive can be designated”; a certainty that he has captured in the development of a vast body of work in which, through drawing, graphics and painting, he has developed a repertoire of scenarios and non-human beings that inhabit the foliage of the Amazon jungle: animals, plants and creatures of an environment that, marked by the poetics of its details, renders an account of a reality different from ours, located in landscapes that escape the conventions established under modern representation systems. An existence so dissimilar to the Westernized life experience that it surpasses the notions of everything that we have assimilated as real and excluded as imaginary; with these limits being created by colonial representational and linguistic determinisms that influence the ways in which we perceive the world, and that therefore give structure to the cognitive categories in which we operate, making it pertinent to ask ourselves: What was the world like before language?

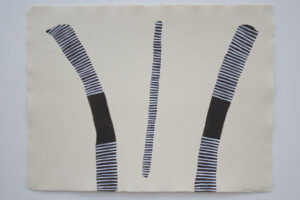

In the culture of the Yanomami people living in Venezuelan territory, there are no forms of systematized writing, nor ‘complex’ tangible manifestations of art, and their own historical records do not go beyond oral tradition, a resource of documentary value that has allowed a successive transmission and compilation of data that today gives us access to certain knowledge of life in the jungle. However, these communities have developed a series of body drawings—non-scriptural—used in the shamanic and celebratory rites of their groups, as well as festive customs, in which they incorporate symbolic elements that, understood as instruments of communication, allow us to discern an aesthetic interest and a need for plastic manifestation. Images that prove that all humans, as social animals, develop symbolic behaviors by giving social value to a displaced element. Even so, from the generalized Western paradigm, we tend to think about the way representation works “in terms of our assumptions about how human language works”. That is to say, we are inclined to assume that all processes are carried out under the logics of representation established as “human”, only because they are socialized and understood as a convention.

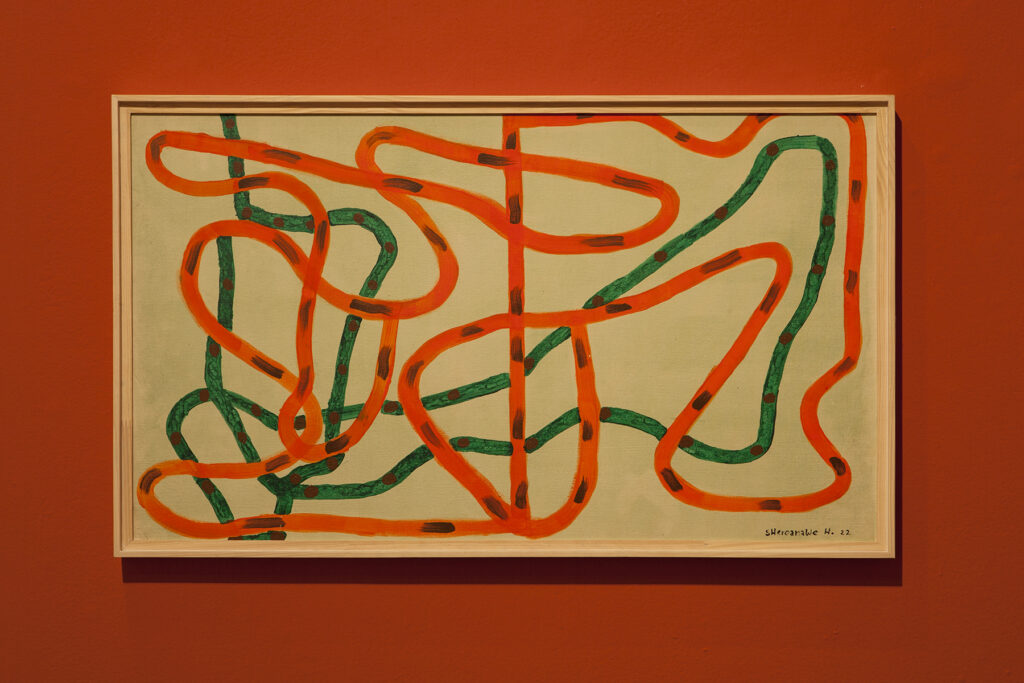

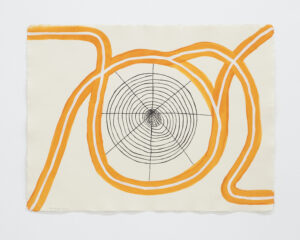

Based on the ornamental customs of the Yanomami bodies, Sheroanawe’s drawings are transferred to paper to present a different way of meaning, in which the artist continues with the primal expression of a language freed from the linear, causal and theological sense with which the “universal” history of the West has been constructed. On the contrary, the images created by Hakihiiwe function as passwords to the world inhabited by the artist, whose contemplative process allows us to access the ancestral memories they contain, activated through story and repetition. Representational modalities brought from his way of thinking about the jungle, “that permeate the entire living world and that have little explored properties, very different from those that make human language special.”

(How other types of beings see us)

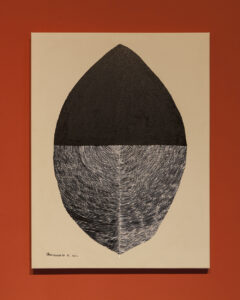

As an expression of ethnic attributes, the language embodies the essence of the community that practices it. This is how studies of indigenous speech allow us to understand—to a certain extent—the link between the way they conceive their statements and sentences and their ways of believing, thinking and acting. Because, although the way other types of beings see us matters, the ways in which they communicate with us (and us with them) also matter. For this reason, understanding the logical categories and heterogeneous temporalities of Yanomami stories involves much more than their translation into Spanish. And although, “within the broad syntax of the world, different beings adjust to each other”, when trying to mediate through words, the linguistic displacement between these cosmogonic limits becomes insufficient, as it cannot encompass socialized meanings existing only in the original language. Thus, we find ourselves in front of a feather of a helmeted curassow in Titiri Mahekii Ishi Ishi [Black Feather of the Night] (2022), about which Sheroanawe comments—in Spanish—that:

A long, long time ago there was no night. It was pure day. They went hunting during the day, they looked for food during the day. Until the head of the community fell into a deep sleep. A helmeted curassow arrived and began to make love to his wife. A lady went to warn him and said: “Wake up, wake up! They are making love with your wife.” So he got up and grabbed an arrow, and went to the mountain where this animal was singing. He got closer and closer to the sounds and pierced the bird’s chest; its feathers fell out. And so the night came.

The complexity of this dynamic of meaning extended to language, images and objects, allows us to determine – always in collective terms – a series of conventions about what’s real (socialized value) and what’s imaginary (what exceeds what is socially valued). Even so, the normalization of the oppositions between these two behaviors means that when we approach indigenous mythologies, we judge a narrative—such as the Yanomami origin of darkness, the product of the act of a bird that copulates with a woman—under the rational criteria of an imaginary behavior, which the “oscillation between images makes susceptible to displacements, outside the cycle that ensures the satisfaction of a natural need”. That is to say, it exceeds what is socially recognized by our “realistic” culture.

But the images are not necessarily concepts, and therefore, they are not isolated in their meaning. For this reason, the works of Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe go beyond the traditional semantic schemes of symbol and connotation, to propose a contemplative experience, expanded, multidirectional and deeply related to its context, the jungle. As a tool to approach his reality, the drawings present in his individual exhibit Parimi Nahi [The Eternal House of the Shaman] (Abra Caracas Gallery, Venezuela, 2022) show a universe of images lived by the artist and told from their names: Mashitha weheti [Drying soil], Rerekerimi [Long-legged insect], Isharomi shinaki [Jay’s tail], Opo moshi [Tobacco caterpillar], among many other details whose phonetic richness is combined with the sensitivity of Hakihiiwe’s stroke; a refined language in which the union between memories, imagination and their representation strategies confirm that, in order to combine richly, it is necessary to have seen a lot – and we can add that, in order to deeply understand the environment, one must relate deeply to it.

Together, the drawings, paintings and monotypes presented by Sheroanawe in The Eternal House of the Shaman make up an archive expressed from the perception and construction in which the Yanomami develop their existence: linked in harmony with nature. Very distant from the Western perspective under which landscape art has been understood, characterized by an objectification of natural elements that—whether intentionally or not—is close to colonial companies that find a resource for exploitation in nature.

(The archive of signs)

Since archives are the law of statements, these are “neither the mere transcription of thought into discourse, nor the sole set of circumstances.” Hence the complexity of Sheroanawe’s work, in which the archive structure functions to give order and decibility to this system of meanings and relationships between images, symbols, stories and meanings in which the artist opens himself to the world and the world opens itself to him. This ordering system of Hakihiiwe’s archival intentions becomes more notable in previous works, such as the series of drawings Kamie ya uriji pi jami Parawa ujame theperekui uriji terimi thepe komi kua [Where I live, in my jungle and in the Orinoco River, all these animals also live] (2018), in which the artist selects, classifies and orders imagined images: those converted into “sublimations of archetypes rather than reproductions of reality.”

In this operation in which the image (drawing) and the word (name) allow a process of synergy typical of human imagination, Sheroanawe uses the most primitive functions of language, not only to facilitate recognition among an existing group, but to constitute a new one: an us whose condition is formed from shared aesthetic judgments, “as a certain dynamic and unstable encounter, which, without always coinciding, points, aspires or tends to produce a significant, and as such, collective communication.” A group that manages to see the world through the artist’s images which, being understood as passwords, follow one of the most precious virtues of language: preventing us from dying. This is how, in its intention to name the living, Hakihiiwe’s work allows us in turn to know the fragility of a reality threatened with its disappearance and the consequences on nature of the centuries of excesses of modern subjects.

Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe, Hi i hipe amakuripe [Logs with iridescent traces], 2021. Acrylic on cotton paper.

In Hakihiiwe’s work, the life of signs does not exist only in the present, but also in the imprecise and possible future. And, after being long seen as a resource made available for human use, the Amazon jungle currently faces the results of the exploitation of a habitat at maximum risk. Subjected to the genocide resulting from the gold rush and the current circumstances of illegal mining in the Venezuelan Amazon jungle, the numbers of the Yanomami population decrease drastically as time goes by. As a consequence of this situation, the shared living memories of this people are more than ever at risk.

For Eduardo Kohn, in the life of signs, the future is closely related to absence. Thus, demonstrating that signs represent what is not present (or what may no longer be present), the work of Sheroanawe Hakihiiwe gains a vindicative value in the face of the fragile existence of the Yanomami groups in Venezuela. Hence, “in an active world, in a resistant world, in a world to be transformed through human force,” Hakihiiwe’s work acquires the category of imagined archive of an entire living community. An archive of suspended time, in which the premise that links being to name makes more sense than ever: because we cannot name that which is lifeless, and even less so if it has been killed by us.

29.03.2024

Projector

Ana Pi

23.03.2024

Opinion Cartografía sentimental de la brutalización en curso Argentina, Latinoamérica

Duen Sacchi

22.03.2024

Marginalia

(Español) La Revuelta

Comments

There are no coments available.