15.09.2017

By Lorena Peña Brito, Zapopan, Jalisco, México

July 27, 2017 – November 6, 2017

Do you like how you look?

Yes. It is you!

You look like that

Do you like how you look?

Svyato, Victor Kossakovsky

The Zapopan Art Museum (MAZ) has sought to give a twist to the idea of “collaboration,” to which end it created the program entitled Doble, designed to open up a narrative proposal that follows a single line of discussion while avoiding any “forced” collective work. The program invites two artists to think at the same time about a particular issue, yet work independently.

Last July, the MAZ proposed that artists Edgar Cobián and Octavio Abúndez take up “duplicity” as a jumping-off point from which to come up with artworks, yet with no contact between them. Sed de Infinito is the program’s first exhibition and presents two projects in one. Divided by a partition within the museum gallery, both unfold as a stratum behind the other; circumstantially, they use identity as an anchor.

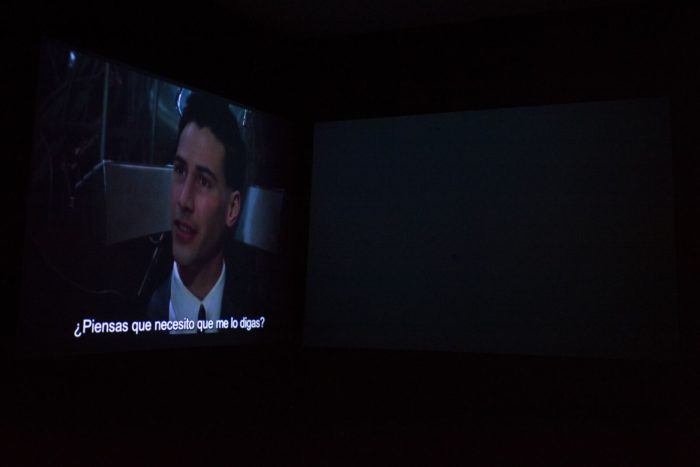

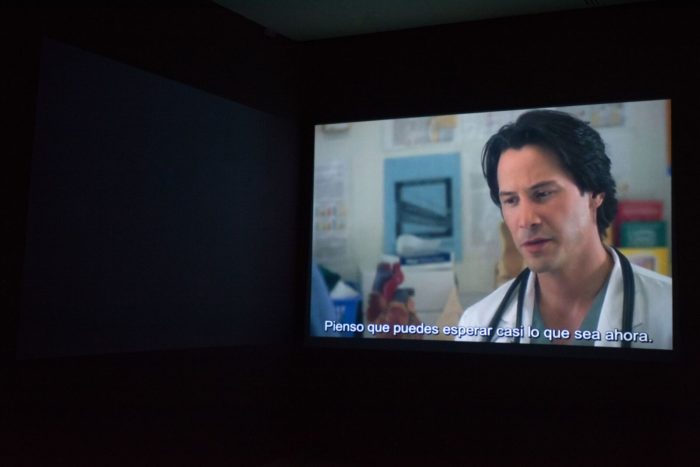

El Sueño (The Dream, 2017) is the project Octavio Abúndez presents. Visitors make their way down a gray hallway where they find traces of the editing process for an unpublished script, then find themselves in a large video screening room. There are two simultaneous projections presenting the same actor, Keanu Reeves, in two different films. It is a montage of film clips used to create a script that unfolds based on the questions “who am I?” and “why am I that way?”. The main character of this exquisite cadaver shifts personalities and ages during the sequence. He questions himself, his double, as if it were his subconscious. In the end it is revealed the exchange was a dream. This piece comes from the series Podríamos Estar Mucho Mejor / We Could Be So Much Better, which the artist began in 2015, that at first seeks to use cinema as the material for a work of post-production and secondly attempts to establish a continuity of works related to dystopia. Its origins are research Abúndez began on films like Terminator, Aeon Flux, Mad Max, Blade Runner, etc. After a period of two years he has assembled an archive that ranges in a number of directions and is articulated based on a memory exercise that makes evident certain characteristics of the consumerism popular culture articulates.

El Sueño is the second layer visitors discover when they come into the gallery. Previously, from outside, they have faced a sort of store window in which they catch glimpses of objects that have been attractively superimposed, grouped and arrayed. Edgar Cobián’s project has no specific name but this does imply his contribution to the show.

In recent years, work by Edgar Cobián reconstructs its own system of symbols, initially based on certain random, but frequent elements: hand and glove, clothing, the language of (cultural) marketing, the presence of something sonic, strobes, the colors of the rainbow and happiness. Over time, the elements that seemed mere random and innocent recurrences, justified with a clean and particular finish, have turned into a container for a political, topical and acidic load. Even technique and manufacture are political because he uses them like a hook. Every element hides a psychological and emotional presence behind it that makes reference to the permeability that the economic and political system exerts on individual characteristics and qualities.

Cobián’s perspective on duplicity involves taking up the idea of the mask from diligence, used to cover something beneath it, like a glove, color or cosmetics. The show is more like an installation that resembles a shop window. Sculptures that share the space configure compositions of opposing essences using wooden rods and ties plus apparel, all jammed together. Old wood, phosphorescent plastic, an Alberto Caeiro poem, fake fur, abstract drawings finished with eyeshadow, a screen-saver that lists qualities that advertising says we should possess. We could get glimpses of ourselves there, through a projection of our consumption patterns. For Lipovetsky, postmodernity is pinned on a no-longer-productive, but instead, consumerist capitalism, the center of a new anthropological model. Revolution and morality have been consigned to oblivion, because now our communities are made up of individualist beings for whom the new is old-hat. Narcissus exists, but not in his reflection; because now there is no image in which to take pleasure. It exists solely as some floating thing. Behind the ideological void and the lack of memory in social connection, there is an incessant search for “oneself,” and from a volatile point-of-reference. The showcases are the new imaginary mirror and they call up the same unceasing question: “do you like how you look?”

Both artists’ projects make their own way before a notion of identity but their starting points meet in critical thinking about the consumerist ideology.

Abúndez has stated his work develops based on an historic reflection. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, there is no longer any possibility of a political-economic system other than the predominant one. The triumph of capitalism and the neo-liberal age gives rise in contemporary societies to the search for a future that frequently hinges on its own impossibility. Cinema has been one of the main references in this search as well as one of the strongest vehicles for sating the desire for narratives that evoke it. Hollywood has taken on both spreading the idea of a promising, progressive future as well as the disaster of otherness. As in work by Cobián, there is evidence the mass media, Hollywood movies, advertising and pop culture have created role models for individuals’ evolution in consumer societies.

In turn, Edgar Cobián sarcastically parodies the way power structures constrict to stand on a handful and oppress yet others in a variety of ways. The creation of identity models attached to acquisitive possibilities are also a form of dominance and oppression. Ways of dressing, smelling, arriving at a politically correct yet “convenient for all” morality—a politics of the cosmetic—is the message of mass propagation; another articulation of the system we feed every day.

It is notable that both artists’ proposals derive from pop culture forms. “Fancy”: film and fashion digested for mass culture. Although from a distance—by which I mean on social networks—this seems like a frivolous, inconsistent and superficial show, there’s something that jumps out at this moment from Guadalajara’s museum scene. The exhibition—particularly Cobián’s project—has been derided on the museum’s Facebook page by an audience more inclined toward traditional forms, that alleges the artworks and their conceptualism are of inferior quality. Nevertheless, this is one of those recent shows whose language and narrative almost anyone can perceive as more quotidian, close and immediate. Its resonance is even close to us, especially Cobián’s project. The nearness of materials and shapes to something we collectively assume as feminine and proper to the LGBTTTQ community. Formally, Sed de Infinito feels more closely linked to shopping centers and stores selling makeup, wigs, platform heels—and all the rest of Avenida Hidalgo’s nighttime paraphernalia—than to a museum. What is it, at root, that has so bothered audiences?

Though the Doble program seems confusing and a bit inconsistent, a show that is so pop on the surface and so critical deep down is a surprise on the everyday Guadalajara art scene. And naturally this Pop perspective has not gone down well at all with the conservative Guadalajara that resists the languages of contemporary art. Perhaps this little show can serve to extend questions about the culture of Guadalajara’s identity(ies) as well as its double discourse (though not its double standard).

Lorena Peña Brito is a curator and cultural manager based in Guadalajara, Mexico. She is currently the director of PAOS GDL, a space dedicated to research and cultural production.

Comments

There are no coments available.