14.12.2019

Santiago, Chile

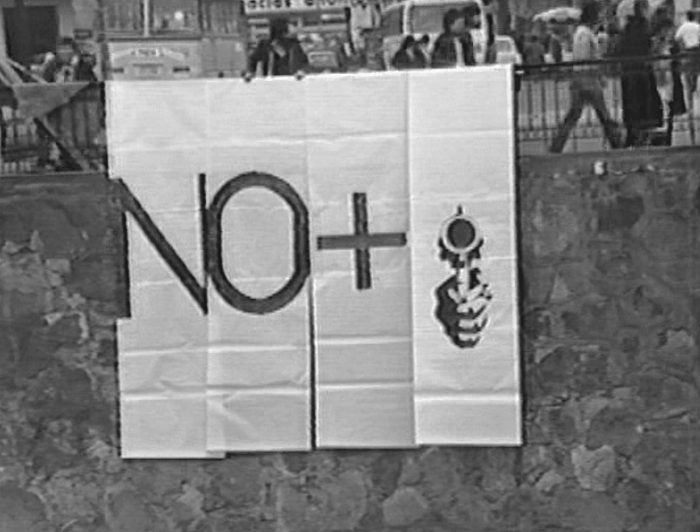

Autore no identificade. 5 de octubre de 1988. Manifestantes celebrando el triunfo del plebiscito que destituyó al dictador Augusto Pinochet se apropian de la consigna «No +» del Grupo C.A.D.A, fotografía análoga 35 mm., Plaza de la Dignidad [Baquedano], Santiago, Chile. Imagen cortesía Lotty Rosenfeld

The still ongoing outbreak that began in Chile during October 2019, also called “The Revolution of 30 Pesos” or “The October Revolution”, is a massive and spontaneous civil movement that emerged from the protests organized by high school students. The source of the students’ unconformity is the same as that of all Chileans: the growing precariousness of life–especially for the working class and for the lumpenproletariat—under the neo-liberal socio-economic model, where the privatization of basic needs as education, pension, health, and transport, together with the complacency of the political apparatus towards the business oligarchy, subject the Chilean people to increasingly adverse conditions. The tipping point was an increase in subway fare of $30 Chilean pesos (CLP) beginning from October 6, scaling the regular ticket to about $830 CLP at peak hours; an unsustainable cost for several families considering that the legal minimum wage in Chile is $301,000 CLP.[1] The high school students articulated a massive dodging of the passage fare by calling users to jump over the turnstiles as a horde during certain times of the day and at strategic stations, planning those days of dodging through chats of online role-playing games and social networks.

The tension severely escalated during the week of Monday, October 14, when the government’s response to the persistent mass dodges was to order Carabineros [police officers] and Special Forces to increase vigilance and repression: they closed station entrances preventing passengers from entering or leaving; law enforcement officials violently assaulted youth and adults identified as dodgers; entire stations were closed off, trains were ordered not to stop at stations involved in the civil action[2] and the operation of the subway was cut off without justification (especially on the lines towards the Conurbano). These provocative measures fueled social protests: protesters tore down the stations’ barriers continuing with mass dodge, some even destroying the entrance turnstiles since Thursday 17.

The growing repression as an answer to the social movement broke out with a day of demonstrations and barricades in the main streets and in the capital’s peripheries on Friday 18, which led right-wing president Sebastián Piñera to declare a State of Constitutional Exception and, even, a State of Emergency in certain territorial areas of the country. This had not happened since the dictatorial period. The current constitution, approved during the civil-military dictatorship, allows a suspension of civil liberties due to a “serious alteration of public order, damage or danger to national security”, punctually restricting the rights of free transit and assembly in addition to the safeguard of the public order under the institutional designs of the president, in this case unleashing the military armed forces to the public sphere.

Susana Hidalgo. Viernes 25 de octubre de 2019. Manifestantes durante la llamada «Marcha más grande de Chile» (más de 1.2 millones de personas) izando la bandera de Chile y de Wajmapu, fotografía digital, Plaza de la Dignidad [Baquedano], Santiago, Chile. Imagen cortesía de Susana Hidalgo

C.A.D.A. Circa septiembre 1983. No +, acción de arte, ribera del río Mapocho al costado del puente Los Carros, Santiago, Chile. Imagen cortesía de Lotty Rosenfeld

In addition to the anti-democratic measures of the dictator S. Piñera–considering freedom of assembly and civil demonstration as prerequisites for politics–a curfew measure was also established between Saturday 19 and Saturday 26 of October, implying that every citizen should enter a private enclosure between said hour in the afternoon to said hour in the morning; otherwise, we risked being prosecuted or chased by law enforcement. However, the brave social movement throughout the country did not stop questioning these measures through the strategy of the “cacerolazo” (or non-violent sound protest by beating kitchen pots on public roads), as well as concentrations and marches in epicenters such as Plaza de la Dignidad [3] [Dignity Square] and Plaza Ñuñoa [Ñuñoa Square], which displayed graphics, graffiti and countless barricades in different parts of downtown area and the periphery of several cities. Despite the mobilization’s effervescence and the general confusion about the country’s situation, as the board of the Arte Contemporáneo Asociación Gremial [Contemporary Art Guild Association] (ACA) we manifested on Saturday, October 19, clarifying: “We reject the violence and repression employed on the civil movement that has emerged to protest this unsustainable situation of multiple cases of abuse, and we firmly oppose the state of emergency, the militarization of the public sphere, as well as the curfew and any measure that compromises democracy, in the same way, we repudiate the eventuality of a future state of exception in the country.”

On Tuesday, October 22, we convened an extraordinary board meeting of A.C.A. to consider how we could face the democratic crisis through civil action and artistic practices. A point of reference was the work of the Colectivo Acciones de Art [Collective Art Actions] (C.A.D.A.), a Chilean artistic group active during the dictatorial period, internationally recognized for its way of innovating with art languages through a series of interventions in the public space. Towards September 1983, during a moment of social outbreak after 10 years of military civic dictatorship in Chile, C.A.D.A. began to push the slogan “NO +” through certain public interventions, including one on the banks of the Mapocho River on the west side of the Los Carros Bridge and on the northern portal of the Cerro Santa Lucia: a quickly appropriated slogan by different protesters and organizations due to the open invitation contained by phrase to be completed by the different maladies experienced by the social body.

A.C.A. 23 de octubre de 2019. Respuesta al No + (C.A.D.A.), acción de arte/protesta, Avenida Libertador Bernardo O'Higgins (Alameda), Santiago, Chile. Imagen cortesía de le autore

Comisión Acciones de Movilización A.C.A. Viernes 25 de octubre de 2019 «Marcha más grande de Chile». [Sín título](Conocidos popularmente como Amortajados), acción de arte/protesta, intervención en el Monumento a José Manuel Balmaceda (1949) de Samuel Román en frente de la Plaza de la Dignidad [Baquedano], Santiago, Chile. Fotografía por Jaime Dames

On Friday, October 25, A.C.A. convened an Expanded Extraordinary Assembly that took place in the building Balmaceda Arte Jóven from 10:30 a.m. In this instance, several problems related to the political crisis were discussed together with the role of the arts and culture in the construction of a new constituent project for the country. Among the various initiatives that emerged from this instance, the Comisión Acciones de Movilización [Mobilization Actions Commission] was created, which began immediately after that meeting with a series of interventions on monuments in public space with reels of raw cloth created to cover them. As part of the mass march that took place that day–later known as “The biggest march in Chile”–the commission moved through different points in the center of the metropolis protected from police repression thanks to more than 1.2 million protesters. The commission toured the following monuments in the following order, fully or partially understanding them: a) Monument to José Manuel Balmaceda, b) Monument to Rubén Darío, c) Unidos en la gloria y en la muerte [United in glory and death], d) Commemorative Column of the Centenary of the city of Santiago, and, d) The Fountain of Neptune. The aesthetics of covering those human figures appealed, on the one hand, to a delegitimization of the institutional power—that which represents the logic of the public monument and the patriarchal conception of the binary bodies of the historical male hero and the female nymph under the discretion of the imaginary of European mythology. And on the other, representing a macabre reference to corpses when covered in a crime scene or the morgue. These interventions attracted the attention of protesters, who came to take pictures with the covered monuments that were popularly baptized as the “shrouded.”

*

Delight Lab is an interdisciplinary artistic group that experiments with light projections on different architectures and surfaces. Founded in 2009 with a digital projection on the facade of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Santiago, this group is made up of the sibling duo Andrea and Octavio Gana, later gaining the support of producer Marco Martínez. The group takes as reference the work of different Chilean artists who have used the public sphere as a medium for different activations such as Lotty Rosenfeld[5] and Patrick Hamilton.

The work of Delight Lab establishes a marked tendency towards artistic activism after the murder of the Mapuche weichafe (warrior/rebel) Camilo Catrillanca in Temucuicui, on November 14, 2018. The night after his political assassination, after an intense day of mobilizations throughout the country, the collective projected the face of the weichafe on some buildings in Plaza de la Dignidad, adding the verse «QUE SU ROSTRO CUBRA EL HORIZONTE» [MAY YOUR FACE COVER THE HORIZON] written by the poet Raúl Zurita. During the first days of the State of Emergency declared by the dictator Sebastián Piñera, this group created a new series of projections on the facade of the emblematic Torre Telefonica next to Plaza de la Dignidad. Through their networks, they broadcasted: «[Delight Lab] declares its support for the just social demands and rejects the declaration of the State of Emergency and the presence of armed soldiers in the streets.» It is worth mentioning that this building, since its inauguration in 1996, is a milestone in the neo-liberal developmental discourse promoted by entrepreneurs during the democratic transition.

Delight Lab. 25 de octubre de 2019. [Sin título], intervención lumínica sobre la Torre Telefónica, Plaza de la Dignidad [Baquedano], Santiago, Chile. Fotografía por Gonzalo Donoso

1.- Saturday, October 19; first curfew day, the group projected the word “DIGNIDAD” on Torre Telefónica.

2.- Sunday 20th; the group emphasizes the plea for “DIGNIDAD!” [Dignity!]

3.- Monday 21; in collaboration with the designer Werner Fett, an intervention was carried out in two parts: “NO ESTAMOS EN GUERRA! ★ / ESTAMOS UNID@S! ✊” [WE ARE NOT AT WAR! / WE ARE UNTIED!][6] in response to dictator S. Piñera who declared that the armed forces were at war with an internal enemy.

4.- Tuesday, October 22; the collective decides to reprimand the plea to the national emblem to sovereignty at the hands of reason or force, through the following slogan: “¿Dónde está la RAZÓN?” [Where is the REASON?]

5.- Wednesday 23; the collective pays tribute to the first five murders of this dictatorship paraphrasing the verse of R. Zurita previously used after the murder of the weichafe C. Catrillanca: “QUE SUS ROSTROS CUBRAN EL HORIZONTE [MAY THEIR FACES COVER THE HORIZON] / Romario Veloz / Alex Nuñez [sic] / Kevin Gómez / Manuel Rebolledo / José M. Uribe.” [7]

6.- Thursday 24; the collective pays tribute to a series of interventions made between 1979 and 1981 by the artist Alfredo Jaar during the dictatorship, known as Estudios sobre la felicidad [Studies on happiness]. Delight Lab asks an open question, both to the Chilean people and to dictator S. Piñera: “¿QUÉ ENTIENDE UD. POR / DEMOCRACIA?” [WHAT DO YOU UNDERSTAND BY / DEMOCRACY?]

7.- Friday 25; last night of curfew, the collective refers to the slogan about the awakening of Chile that circulated through all the protests in October: “CHILE DESPERTÓ / POR UN NUEVO PAÍS” [CHILE WOKE UP / FOR A NEW COUNTRY]. This awakening’s testimony is directly related to the insistence of law enforcement in firing pellets pointing the eyes of Chileans, which resulted in a total of 232 recorded cases of loss of eye vision due to lacerations perpetrated by these institutions.

*

Among the artistic actions carried out in a state of exception, various artists privileged body art and performance as mediums; many of them interested in the sex-generic dimension that underlies the oppression of the armed forces and inequality in Chile. Added to the provocation, the brutality in the force to repress and detain protestors, and the discovery by human rights organizations of different illicit torture centers in places such as the Baquedano metro station and 43rd Carabineros Station[8] in Peñalolén, political-sexual violence, and rape was another way in which corrupt law enforcement officials sought to intimidate protesters and bystanders, specifically women and sexual dissidents. To date, the National Institute of Human Rights records a total of 79 complaints of sexual violence, of which 4 include rapes. Many of the women and dissidents who have been sexually violated—through threats, undressing, humiliation, “squats”, touching, harassment and rape—must remain anonymous to avoid being re-victimized by the torture experienced. However, some women, such as the journalists of the newspaper La Estrella de Arica, Estefani Carrasco and Patricia Torres, gave courageous testimony of the harassment experienced on October 23 to ensure this type of heinous crimes against humanity don’t happen again. Similarly, openly gay medical student Josué Maureira publicly denounced before the media how he was brutally beaten and raped by the service baton of a carabinero at the 51st Police Station of Pedro Aguirre Cerda in the early hours of October 22.

Chilean performance artist Cheril Linett uses body art to question the abuses of the hegemonic power, proposing transfeminist emancipation strategies through desire. Developing a scheme of experimentation and body research of Artaudian type, which she calls the “lubic beast”, the artist has performed a series of individual and collaborative exercises that culminated in a collective performance entitled yeguada latinoamericana.[9] This performance caused a stir in the local countryside through a series of public interventions with feminized bodies (biological and dissident) in different martial and religious ceremonies, as well as in institutional establishments of the country. Through the sorority of feminized bodies and gender violence that emerge from it, C. Linett activates spaces of intersection between art, activism, dance, dissidence, trans/feminism, photography, theater, media and performance: a space for critical questioning on the stage of body action, institutionality and the boundaries between art and politics in contemporary Chile.

“¡Estado de rebeldía!” [State of Rebellion!] was the slogan with which the collective of the yeguada latinoamericana came out to protest in those days of the state of exception. On the first day of actions, on Sunday, October 20, the yeguada took the streets wearing black clothes as a sign of mourning for the lives of the murdered protesters, raising their left fist and exhibiting a horsetail that fell between their buttocks. They activated the posture we call «war position» to face the intimidation of police and military armed with tear gas and pellets and bullet rifles. On the second day of mobilizations, on Tuesday 22, the yeguada is activated during protests outside Torre Telefónica, this time incorporating flares as well as the “hood”, or balaclava, that aids protestors in the frontline—stalling the repression from police cars—by hiding their identity and protecting them from the tear gas. On the third day of activations, on Friday 25, the yeguada returned to the street wearing the horsetails with a pink dress that alluded to the conventional notions of femininity in association with weakness. In addition, a stencil with pink road paint was made on different points of the city center with the slogan “State of Rebellion”, subsequently making a version of the “war position” lying on the road. The first of these stencils was held outside the National Archives building—an important meeting point for feminist protests during the dictatorship around 1983. The next two were held outside the northern entrance of Cerro Santa Lucia and outside the Pontifical Catholic University from Chile, making a final streak in Plaza de la Dignidad. These three days of actions in the public sphere make up a work titled Estado de rebeldía.

yeguada latinoamericana (dir. Cheril Linett). 30 de octubre de 2019. Orden y patria II, performance colectiva en el contextos de distintas movilizaciones sociales, Santiago, Chile. Fotografía por Lorna Remmele

A few days after the state of emergency ended, the yeguada became active again in the public space: this time directly addressing the carabineros in Chile for the sustained sexual aggressions and violations that continue in contexts of civil repression. That time, the yeguada wore wreaths of flowers that spelled each of the letters of the word “VIOLADORES” [RAPISTS], raising the black dress above their heads in a gesture of anonymity and violence, also showing breasts and genitals when lowering the underwear to their thighs. While several companions were kneeling in submission to each end, the bearers of the crowns were in the middle of the body composition lying on the floor with their backs to the ground. The yeguada took this action to Plaza de la Dignidad, and also descended to the closed Baquedano metro station, used as an illicit torture center by police and military. They activated this action in the Monument to the Carabineros Martyrs of Chile (1989), and also outside the 1st Carabineros de Santiago Police Station, the latter on whose facade the flower crowns were installed. Since before this action and during their actions in the public space, the police are in constant tension with the yeguada, especially resentful of the visibility that this last action acquired in the media and social networks. After working in the public sphere, many times we were arrested by carabineros or followed to our homes; they were especially interested in intimidating C. Linett. On Friday, November 8, the performance artists with her partner, a friend, and a passer-by were beaten with blunt elements by a group that presented features belonging to the extreme right just outside their home and operations center of the yeguada. This is not over yet.

——

Aliwen is a critic, curator, teacher, and researcher on issues of art, anarchy, decolonialism, and sexualities. Mapuche warriache, champurria and trans*. Member the Directiva de Arte Contemporáneo Asociado A.G.. Holds a Bachelors Degree in Theory and History of Art of the Universidad de Chile, Monbukagakusho 2020 Fellow of Japanese government to carry out postgraduate studies in artistic curatorship and transculturality. Human rights activist, especially for people from the LGTBIAK + community and people living with HIV/AIDS. Collaborates with media such as A*Desk, Artishock, and The Clinic.

We must consider that a large number of people in the country, including those who write, do not work under the figure of a contract and many times our salary is significantly less than this figure. Mobilizing only one person during the working week by subway –once during valley hours and the second during peak hours- implies under this logic about $1,580 CLP per day and $7,900 CLP per week, or $31,600 CLP per month. This figure responds to more than 10% of a monthly legal minimum wage, and we must add that the majority of workers are the livelihood of more than one person and that several must spend more than this amount on daily transport to their workplace due to their place of residence; especially when they live in the periphery and must arrive at the city center to be able to work.

However, protesters decided to take a risk and sit on the sides of the subway tracks, so they forced the standstill of the subway cars and managed to get inside.

Formerly known as Plaza Baquedano, the name of this square was changed by the social movement in a cyber action in which the name was updated in all applications, pages and internet systems where this was possible, on Monday, November 11.

“NO + Abuses”, “NO + ACRE”, “NO + False Democracy”, “NO + Indifference”, “NO + Military Torturers”, “NO + Misery” “NO + Order and Nation”, ” NO + [Blood] ».

Member of the group C.A.D.A. as well as founding member of the A.C.A.

Both the lighting collective and the designer W. Fett decided to include the icon of a raised fist, which was perceived ambiguously in sex-generic terms.

Currently, the list of those killed by the brutality of law enforcement in Chile during this latest social mobilization scales to 24 confirmed people, while many other cases of deaths in strange circumstances are still under investigation.

In the early hours of Monday, October 21, the National Institute of Human Rights reported that a group of three adults and a minor were “crucified” suspended to an antenna using handcuffs in this compound.

Comments

There are no coments available.