Reports - Chotin' I Prácticas curatoriales - Caribbean Latinoamérica Panama

Reading time: 8 minutes

08.12.2023

Ana Laguna; curator, researcher and independent writer reflects on Chotin’, the first meeting on curatorial practices in Latin America and the Caribbean held in Panama last October. An important initiative to rethink curatorial practice within institutions and their margins in the region.

In a small museum in a small Central American country, Chotin’ Prácticas curatoriales desde Centroamérica y Caribe (Chotin’ Curatorial Practices from Central America and the Caribbean) takes place for the first time. The MAC Panama, the MCA Chicago and the MoMA PS1 lead this curatorial meeting, under the curatorships of Carla Acevedo-Yates (MCA Chicago), Elena Ketelsen (MoMA PS1) and Juan Canela (MAC Panama), and in this edition with coordination by Jennifer Choy (MAC Panama).

If we were inhabiting an ideal world, this would have been a good start for the text. But I cannot mobilize a writing exercise on this project without establishing the context and situation that was experienced in Panama during Chotin’ and that continues to be experienced weeks later.

On October 20, 2023, the National Assembly of Panama approved a mining contract-law that had been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court of Justice; this heated up the protests against mining that had been happening for a few days. With a speed that has never been seen before, that same day, the president signed it and it was published in the Official Gazette, completing the process to make it permanent. This became the straw that broke the camel’s back. Today, as I write this reflection, we can say that several of the representatives who voted in favor of this have come out, apologizing to the people and admitting that, in fact, they did not read the extractivist contract that they supported and that puts biodiversity, water, and the sovereignty of the country at risk, and that will displace families from their homes.

The protests intensified, crowds multiplied throughout the country and repression by the police was at its maximum level. It should be noted that the magnitude of these protests had only been seen in the Civilist Crusades against the dictatorship at the end of the 1980s, when the same party that currently rules the country was in power.

So, this is how Chotin’ begins…

MAC Panama explains:

Chotin’ is proposed as a series of meetings to share experiences, reflect, and generate alliances around curatorial practices located in Central America and the Caribbean, expanding to Latin America, and also including practices developed from the US with a focus on the region. The main objective is to generate a place for meeting and exchange with key agents from other museums and projects, articulating a space for reflection, discussion and debate around the particularities of curatorial practice in our geographies.

It consisted of a closed program that was later complemented with activities open to the public. This meeting was the first of its kind in Panama. The topics for the different conversations were chosen based on the problems that arise from working with the characteristics of Latin American contexts: scarce budgets, working with the public and in a community manner, new museologies, the constant lack of equipment, environmental, social and political factors.

Early on Monday, October 23, we all woke up so we could get to the museum before they closed the streets—and, in the case of the guests, before they closed the bridge they would have to cross to get to the city, or they would be trapped on the other side. As the days went by, we were able to understand the times with which we could work and how we could move from place to place to try to comply with the program, which was presenting a great challenge. This made clear the adaptive skills necessary to work in these territories.

This was a very relevant way to start the day’s session called “How do we do what we do?” This session would address issues related to the particular circumstances when developing curatorial practices in contexts with diverse limitations.

This first session included interventions by Gladys Turner, a Panamanian curator, who showed us a study carried out through surveys for Latin American artists, from which it was concluded that many artists perceive curators as inaccessible.

This intervention by Turner began a discussion about what is expected of a curator. And, also, about how the system can be restructured so that artists can have a dignified life.

It happens that in the artistic world there are two extremes, clearly divided, but one does not work without the other. In art, in most cases, the people who maintain power are people from the upper social classes, a situation that is constant in the different institutional teams. Curators change, artists pass through, guides come and go, but the boards of directors remain the same. However, these people with power in the art world would not have that world without the artists, curators, guides, or any other employees of their institutions.

This first day, after two other interventions by Adan Vallecillo and Marina Reyes Franco, the question of context remains: what is ethical today, how time is managed and the reconstruction of memory, and how small institutions, NGOs and self-management projects remain open.

So, how do we do what we do? Well, resisting. Doing collaborations with other spaces to divide the costs. Being on alert 24/7 because we don’t know what can happen from one second to the next in our fragile contexts. Taking care of each other. With radical tenderness and enjoyment, as Patricio Majano mentions. With affective collaborations. With generosity, in the words of Reyes Franco. With empathy. Acknowledging each other. Finding ourselves in each other and working as a community. Even if, at some point, we have to surrender to the reality of hosting weddings, business events and renting out our spaces in order to keep the lights on.

Elena Ketelsen, when talking about communities, makes very clear the difference that we have to understand between “working with the community” and “working as a community.”

One works “with” the other seeing them from afar, while the second means working together and from a place of conversation and understanding.

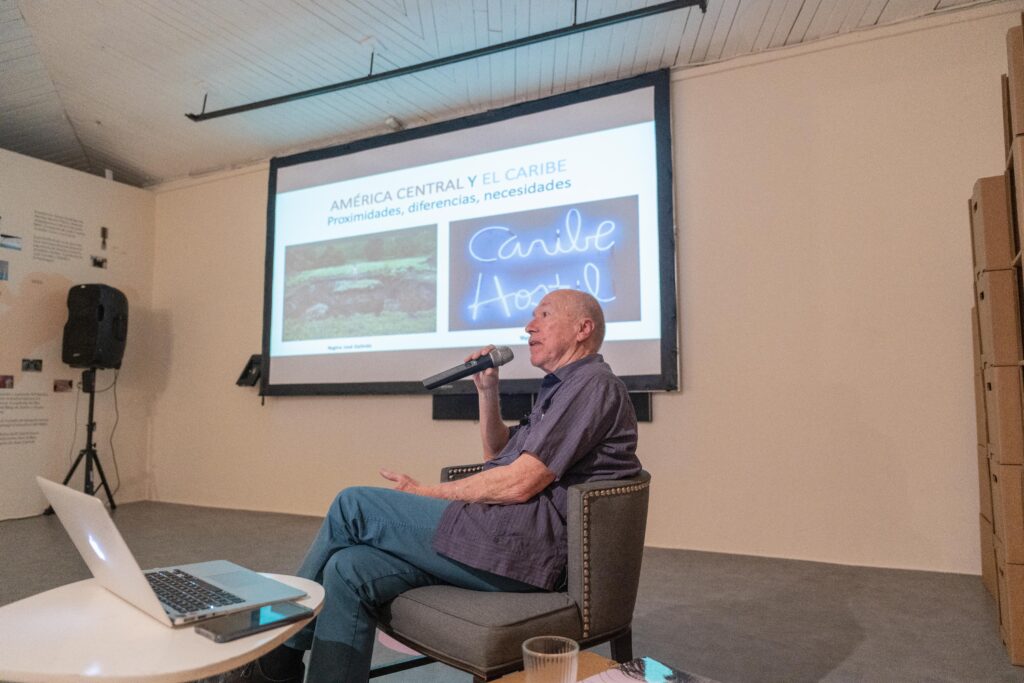

But this still leads us to the importance of knowing where we speak from. In his keynote lecture, Gerardo Mosquera establishes the foundations of the Latin American and Caribbean context, and proposes that curatorship has to be responsive to a circumstance. One has to understand by situating oneself in the context.

The following days, although public events were cancelled, closed meetings continued where Ketelsen, Maya Juracan, Adrienne Samos, Keyna Eleison, Carla Acevedo-Yates, Daniela Morales and Paula Piedra from TEOR/eTica, Sara Hermann, Emiliano Valdes, Maria Lucia Aleman, Ericka Flores, Manuela Moscoso, Diane Lima, Patricio Majano, Esperanza de Leon, Yina Jimenez Suriel, Pablo Jose Ramirez and Pablo Leon de la Barra intervened.

Throughout all these days of conversation, some questions remained with me. What is ethical? What is ethical when you ask where the money comes from? Or, what is ethical about continuing to participate in a program instead of being on the streets? That’s why, during this program, there was constant conversation about everything that was happening, since we all witnessed protests and anti-riot forces ready to attack people who were marching peacefully. At night, for the locals it meant going to protest – and it still does –, each of them joining groups where they are most needed. Esperanza de Leon made it very clear when she commented on her fight in the protests in Guatemala. We have to understand and recognize where we are helping the most and when it is time to step back and look for other ways to collaborate according to our abilities.

It wouldn’t be strange to feel imposter syndrome when listening to these people. Am I good enough to be there? With people who have held biennials, created spaces, made multiple publications? And that was when Keyna Eleison spoke of “the first time.” Being the first ones, changing the discourse. In Panama, a country with a single 61-year-old contemporary art museum, with a ministry that has only existed since 2019, we are now experiencing many first times, first curatorships, first racialized people as curators, firsts and more firsts. And then, exhaustion sets in—if I am the first with this title or with this opportunity, I have a great responsibility not to be the only one and to do it well, always well. It was Sara Hermann who in her speech said that we have to learn to fail better, because making mistakes is inevitable. Eleison, on the last day, names the space as “the house of error.”

How do we ensure that what we do is not fleeting, and that the teams remain and grow together? How do we go from being the first ones to not being the only ones?

Hermann says that there may be healing in our training. Perhaps due to the collective effort to heal a cultural, collective memory, and ourselves?

On one of the days, we talked about the bubbles in which our bodies are found and how these represent an institutionality. “They want our ideas, our work, our research, but they don’t want us, what we represent.”

What is the purpose of what we do? Trying to find meaning in this profession, I think, will be something that we will spend our lives doing, because just as there is no exact definition of what curatorship is, there is no concrete answer to this question today. However, we can find relief in understanding our responsibility and our place of enunciation.

I write this reflection today where I provide more questions than answers to seek relief from now, from this present, and assuming my responsibility as a curator. As a curator who defines herself as Afro-descendant, woman, Latina. As a curator who, for now, works from institutions. As a curator who has a lot left to learn.

[1] Chotin’ comes from the Panamanian word chotear, which, according to the Panamanian Spanish Dictionary written by Prof. Margarita Vasquez (specialist in Panamanian Literature), means: when two people greet each other by joining their open hands. For example: “Chotea las cinco” (“High five”).

Comments

There are no coments available.