15.09.2022

Through a historical journey, Mónica E. Kupfer makes a critical review of the path that women have opened in art institutions.

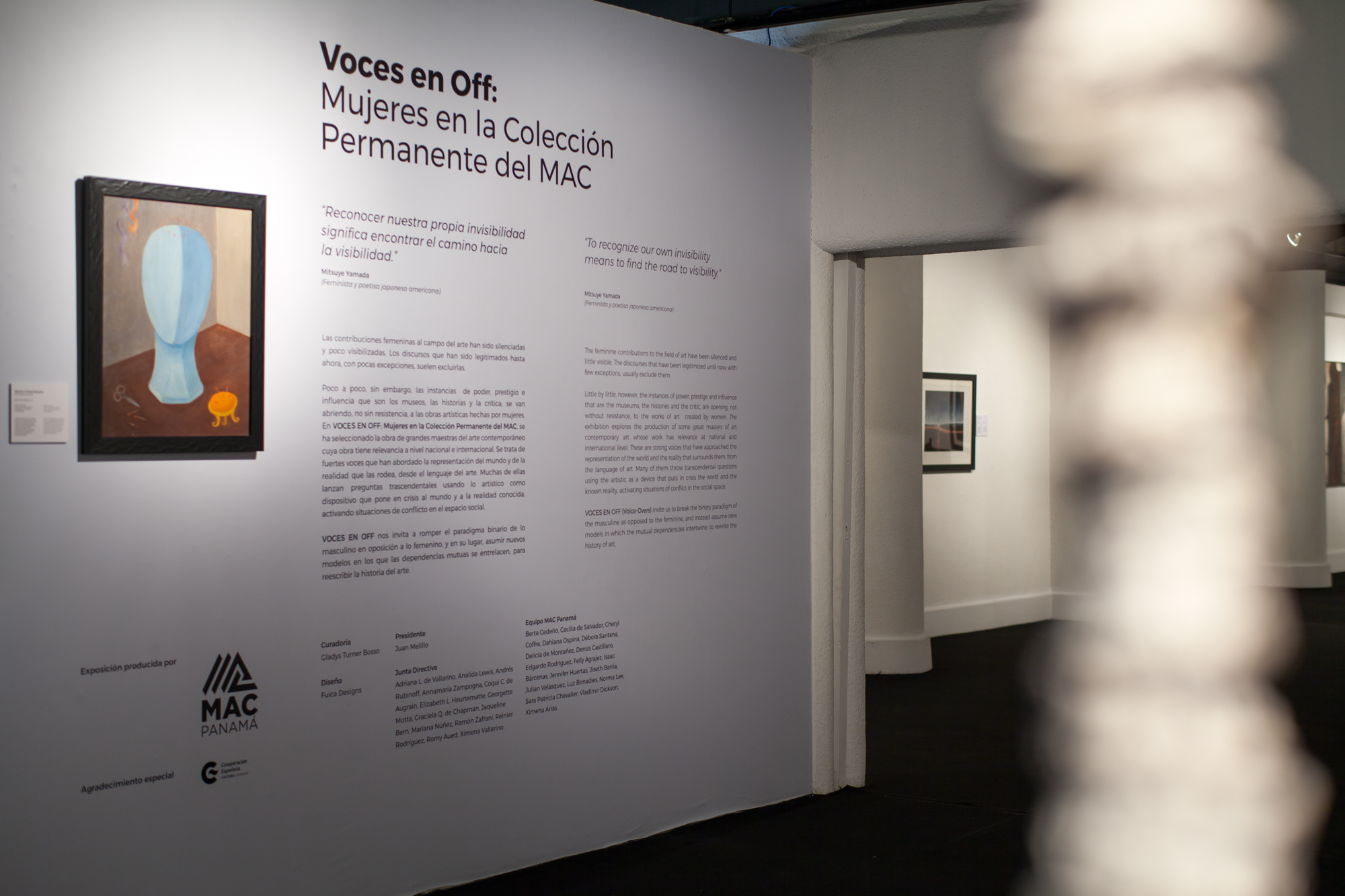

An error declared as a historical fact in a recent article in Terremoto magazine announced that “in the Panama museum, to date, there has not been a single exhibition exclusively of women artists.”[1] The comment caused immediate reactions. Especially because the MAC Panama is a museum where women artists have found support throughout its 60 years of existence (first as the Instituto Panameño de Arte or Panarte, and since the 1980s as the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo). As for a “women-only exhibition,” we only need to recall the exhibition Voces en off: Mujeres en la colección permanente five years ago, curated by Gladys Turner Bosso, with works by seventeen women artists from ten countries.[2]

That false statement brings to mind a long list of events and exhibitions. In recent decades, the MAC has presented not only important retrospectives of Panamanian artists such as Teresa Icaza, Coqui Calderón and Sandra Eleta (which, moreover, were curated by women), but also solo shows of well-known national and international women creators like Cecilia Paredes, Isabel De Obaldía, Amalia Tapia, Alicia Viteri, Claudia Gordillo, Maya Goded, and Iraida Icaza, to name a few. For my part, in 2011, I presented at the MAC the book Las mujeres en las artes de Panamá en el siglo XX [Women in the arts of Panama in the 20th Century]; and, in 2013, the exhibition Perceptive Strokes: Women Artists of Panama, which I curated for the IDB Cultural Center in Washington, D.C., featured a significant number of works on loan precisely from the MAC´s permanent collection.

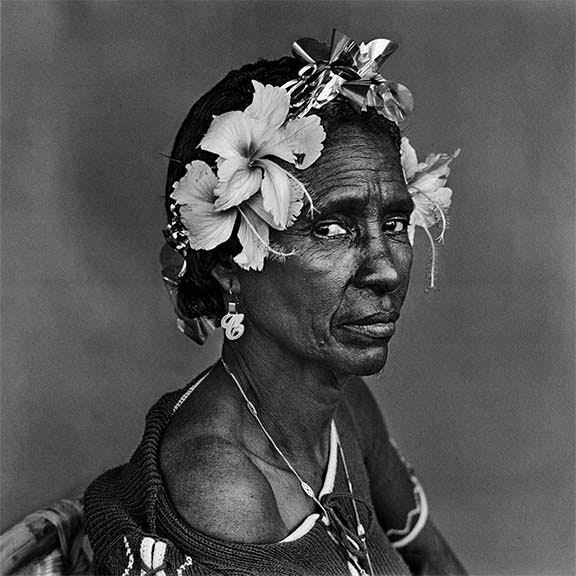

There are several women artists who have marked milestones in the history of the MAC for reasons that go beyond their gender. In 1982, Sandra Eleta exhibited Portobelo viene al museo, a multidisciplinary event whose inauguration included not only her extraordinary series of photographs of people from the town of Portobelo on Panama´s Caribbean coast, but as part of the audience, a large number of its Afro-Panamanian inhabitants, who were also her friends and neighbors. That night, which would be described in the newspaper La Prensa as a “small revolution” at the MAC, Eleta also presented her first “audiovisual” work, a clear precursor of video art in Panama.

Two years later, Alicia Viteri made an impact with her exhibition Espacios pictóricos, which incorporated a huge mural 3 meters high and 7 meters long, centered on the themes of carnivals and funerals. Moody, enveloping lighting together with the sound of music and urban noise produced the sensation of being immersed in the installation and artistic action, the first work of its kind in Panama. So much so that the life-size human figures painted on the mural seemed to blend in with the crowd in the room. That same year, Panamanian sculptor Susana Arias exhibited striking large-scale ceramic sculptures that revealed an innovative way of understanding and self-expression with clay. And around that time, among the foreign artists invited to the MAC were Liliana Porter from Argentina, Ana Mercedes Hoyos from Colombia, Leonilda González from Uruguay, and Olga Dondé from Mexico.

Despite the list of exhibitions that have highlighted the artistic work of women, it remains a reality that, over the years, the Panamanian museum, like so many other similar institutions, has presented more exhibitions of works created by men. In fact, when Panarte was founded in the 1960s, there were few women artists in Panama who exhibited their works in public, among whom painters such as Coqui Calderón, Olga Sánchez and Trixie Briceño stood out. However, a significant number of women not only formed part of the founding group of the institution, but continued to be essential members of its board of directors. In addition, of the twelve executive directors the museum has had in its 60 years, ten have been women and a large percentage of the exhibitions—of all kinds—have been the product of the work of women curators.[3]

In contrast to that early period, during the 1970s, with a new local creative generation and an increasing number of invitations to foreign artists, Panarte presented a total of 22 solo exhibitions by women. There were too many to list, but outstanding among them were Sandra Chanis and Olga Sinclair from Panama, as well as Carmen Wenzel and Marta Chapa from Mexico, and Olga de Amaral and Maria de la Paz Jaramillo from Colombia. In 1979, it was two women—Viteri and Calderón—who founded the Panarte Graphic Arts Workshop, which today promotes the work of a new generation of Panamanian printmakers.

The MAC has also been the stage for politically and historically motivated exhibitions, with a significant participation by women artists and curators. In November 1989, the museum showed the bold exhibition entitled MANiobras, with works in which Isabel De Obaldía openly attacked Panama’s dictatorship. A few months later, Coqui Calderón exhibited her Serie Panamá, composed of paintings that alluded to the years of political protests and military oppression. In 2014, 1964: Arte, Política, Panamá commemorated fifty years since the tragic clashes between Panamanian students and U.S. soldiers during the riots on January 9, 1964. And in December 2019, thirty years after the fact, the U.S. invasion of Panama by the United States was commemorated with an encompassing, moving, educational, and necessary exhibition entitled Una invasión en cuatro tiempos, curated by three women. Highlights included a performance and installation by Panamanian artist Ana Luisa Tejera, titled Bla-bla-bla, as well as the incorporation of books, photos and memorabilia from that military confrontation, the result of an open call to the public for contributions to the show.

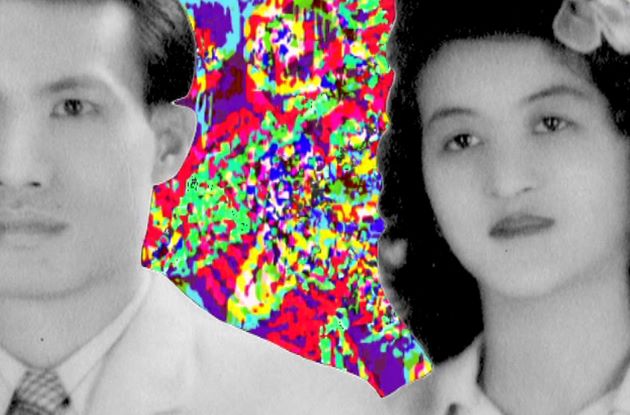

On the other hand, the Panama Art Biennial, founded in 1992 and held eight times until 2008, was an event whose jurors, selected artists, and award winners came from diverse communities that converge in the Panamanian and Latin American cultural ecosystem. In the early years, artists such as De Obaldía, Haydée Suescum, Lezlie Milson, Ana Elena Garuz and Fabiola Buritica, among others, received awards and honorable mentions. The Biennial was also inclusive and progressively innovative in terms of the presentation of new artistic media. The 1998 Biennial marked a turning point when the sculpture prize was awarded to Iraida Icaza for an assemblage whose central element was a photographic composition.

Since the 1990s, the solo exhibitions with innovative works at the MAC have included Suescum’s large-format paintings on paper (1995), De Obaldía’s exceptional glass sculptures (1993 and 2003), Milson’s overtly feminist installations (1999), Iraida Icaza’s photographic show El museo olvidado (1999), and Emily Zhukov’s three-dimensional pieces (2001). Other noteworthy women have participated in group exhibitions, including Donna Conlon, Rachelle Mozman, Ana Elena Garuz, María Raquel Cochez, Pilar Moreno, and Mira Valencia; as well as new artists in recent exhibitions, such as Ana Sofía Camargo, Giana De Dier, Laura Fong Prosper and Risseth Yangüez.

Over time, group exhibitions at the MAC have also featured greater diversity in terms of social and cultural inclusion, beyond gender. The 1964 exhibition (2014) included graffiti artists and muralists; Expresión furtiva (2015) highlighted art inspired by skateboarding; Panachina (2016) featured work by Panamanian artists of Chinese descent; Los rebeldes: la tradición in(di)visible (2018) showed the contribution of Afro-Panamanians to the arts and popular traditions; Dulemar: Una mirada contemporánea al arte y la cultura gunadule (2019) opened the field for the artistic expressions of native peoples; and the presentation by artists Lolo and Lauti of an interpretation of the opera Carmen with members of Panama’s drag and trans community (2019) represented an opening for LGBTQ artists.

Among the exhibitions in recent years, Mesotrópicos (2021) brought the Panamanian public up to date with the “new social and geopolitical imaginaries of the region” of Central America, the Caribbean and Mexico, with works by 30 artists including numerous women, such as Lucy Argueta, Patricia Belli, Donna Conlon, Regina José Galindo, Priscilla Monge, Vanessa Rivero, and Andrea Santos. And during the first half of 2022, the MAC showed Guardar semillas en el cabello, an exhibition that combined works from the MAC’s permanent collection with art from “communities that historically have had difficulties in gaining institutional visibility,” such as women, indigenous, Afroamerican or LGTBQ artists. During the same period, La pisada del Ñandú (o cómo transformamos los silencios) offered an exploration of the effects of colonial processes and the construction of social and gender identities, with the incorporation of material from transvestite, trans and non-binary archives, which contributed to questioning the local imaginary on sexuality and binary gender.

There is no doubt that the history of art in Panama, as in so many countries, has been dominated by cis men and, more specifically, by painters, who have a greater number of exhibitions and works in public and private collections. The process of correcting both historiographical errors regarding the suppression of minorities or discriminated groups (such as saying that there have been no art exhibitions by women) and historical errors, like the systematic and structural exclusion of such groups, is imperative. At the MAC Panama, without necessarily leaving aside well-established artists, the program has increasingly focused on –and will surely continue to promote in the future— the investigation of art produced by a diversity of collectives and individuals, as well as by creators from marginalized communities, demonstrating and exploring their artistic values as well as their social, sexual, political and historical implications.

Maya Juracán, “A Future Without the Need to Name Ourselves”, Terremoto: A Burning Song, n. 21 (Mexico City, October 2021-January 2022), p. 108.

In response to a letter from Gladys Turner, Terremoto removed the erroneous information from the digital version.

The limited space of this article does not allow me to list all the individual directors and curators. For more information, visit the MAC-Panama website.

Comments

There are no coments available.