24.04.2021

Mesotrópicos prompts reflection on the links between our natural environments and colonial histories, how these have shaped the present cultural moment and continue to inflect and hamper the struggles for socioeconomic and gender-based equality as well as environmental justice.

The exhibition Mesotrópicos: Ficciones transitorias y tempestades afectivas (Mesotropics: Transient Fictions and Affective Tempests), at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Panama City, Panama, prompts viewers to look down, to consider the territory underneath their feet, and then to think outwards on the geopolitical and affective relationships between the countries that make up the Central American isthmus and neighboring Caribbean islands. Organized by the Honduran artist and curator Adán Vallecillo and composed of artworks made by 31 artists from Panama, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, and Mexico, Mesotrópicos takes up both floors of the museum, with a handful of works installed outdoors. Both individually and collectively, the works weave together ideas relating to place-based histories; colonialism and its cultural and economic effects; environmental history; architecture and domestic space; and migrations of living beings, ideas, and visual forms.

The exhibition is also self-reflective, prompting questions about what contemporary art means in a region that may be borrowing the term from elsewhere and how it participates in a regional history of art. It signals this self-awareness through quotes on the walls that bring in the voices of artists and thinkers from the region, as with Madeline Jimenez Santil’s assertion: “No existe arte contemporáneo en nuestras geografías, pero ficcionamos ese concepto y sus lógicas de producción, circulación, y consumo.” (There is no contemporary art in our geographies, but we make a fiction out of the concept, and its logics of production, circulation, and consumption.) Alluding to its participation in a type of exhibition historiography, Mesotrópicos refers to the show Mesótica II, organized by curator and cultural producer Virginia Pérez-Ratton in San José, Costa Rica, in 1996, as an important antecedent. A groundbreaking showcase of work by artists from Central America, Mesótica II was a sort of rejoinder to Cuban curator Gerardo Mosquera’s indication, following research for the exhibition Ante América (1992)—co-curated with Rachel Weiss and Carolina Ponce de León—that art from Central America was simply unknown and therefore not part of Ante América.[1] Mesótica II was a catalyst, and it was followed other exhibitions that considered art from Central America from a regional perspective, including Estrecho Dudoso in Costa Rica (2006), and the Biennial of Visual Arts of the Central American Isthmus (BAVIC), which began in the late 1990s but has not been held since its last edition in 2016 in San José.

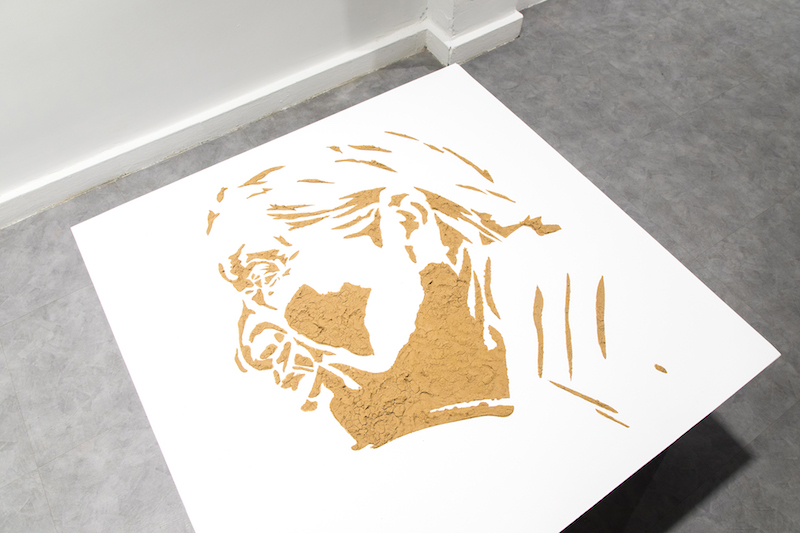

It’s impossible not to view this exhibition through the prism of the COVID-19 pandemic. Not only is it one of the few exhibitions I have seen in person since the beginning of the pandemic in the Americas in March 2020, but it is notable that its research, organization, and installation by Adán Vallecillo occurred in midst of it. It meant severe restrictions for travel and in Panama strict quarantine orders that lasted into 2021. As Vallecillo explains in an interview video, most of the works were produced in Panama with detailed instructions from the artists, reflecting a mode of working that demanded trust and a relinquishing of control for many artists, and that to his and their credit has yielded a rich showcase with works that partake in a host of shared political, environmental, and social concerns beyond their shrewd arrangement in discrete rooms within the museum. While Mesotrópicos presents artworks across media, including photography, drawing, painting, installation, and video, is it the recurring presence of soil and clay that seems to permeate the experience, underscoring the relationship to place as a physical, tactile entity as much as one connected to imaginaries. Salvadorian artist Melissa Guevara invites viewers to take clay directly into their own hands to make small sculptures to leave behind on a table; in COVID times it feels like a dare to touch something in a public place. Clay is also powerfully invoked in stenciled bas-relief portraits of indigenous leaders, the work La memoria de los cuerpos indígenas (The memory of indigenous bodies, 2021), by Salvadorian artist Marilyn Boror Bor. The stenciled portraits convey the dignity in the two face’s features while alluding to the topography of these Indigenous women’s territory: the Lacandona Jungle that spans northern Guatemala and southern Mexico. In both cases, the labels indicate, the clay was procured locally, from the indigenous territories of Guna Yala, in northeastern Panama.

The approach of Mesotrópicos to matters of gender and feminism is sly and sassy, proposing through the paintings of Rebeca Martínez Monge and the outdoor installation by Madeline Jimenez Santil a sexier way to challenge gender roles—and perhaps another way to think about “affective tempests.” One of Monge’s skilled, caricaturesque paintings casually defies the stereotypes of “nudes reclining” so pervasive in the history of western art, while challenging the at-times facile connections drawn between women and nature. Jimenez Santil’s site-specific installation spells out the words “call me mamacita” with letters shaped out of dirt on a raised semi-circle of soil, literally sowing the idea that she might like being called “mamacita,” asserting personal and sexual agency. Its installation outside the museum literally welcomes the viewer, setting the tone for an exhibition in which many artists challenge, or at least expose, colonialist and heteropatriarchal narratives that have shaped the region’s culture and history. Alongside a graphic mural by Panamanian artist Andrea Santos painted on the museum’s exterior walls, and Mexican artist Vanessa Rivero’s totem figure, these outdoor installations foreshadow an exhibition whose works point towards their rootedness in their respective environments, as well as a showcase in which the curator, without overt signaling or self-congratulatory gestures, invited more women than men to participate.

Stories of complex movement and migration emerge strongly in a group of works exhibited on the second floor, anchored by the central installation Siguiendo el camino amarillo (Following the yellow road, 2012) by Honduran artist Leonardo Gonzalez. The contrast of the small yellow kids’ backpacks, strewn about a heap of dirt, flirts with the reductive but considered in light of its title, powerfully evokes the hope of the yellow brick road from Frank Baum’s The Wizard of Oz with the hopes for survival of so many Central American children migrants who arrive at the U.S. border. The packs function as uncanny markers for the thousands of young people who carry them on their backs; the soil alludes to the ground they traverse and climatic conditions they face; and the title conveys the elusive character of what supposedly awaits them at the end of arduous journeys. It’s discouraging to realize that this work is nine years old and so little has changed. Salvadorian artist Beatriz Cortez’s installation Inframundo (2019–21), presents visitors with five small anaglyph lightboxes, each displaying a photograph documenting a performance, which in turn relays complex histories of violence in El Salvador, on the one hand, and biological U.S. imperialism, on the other, including near-comedic approaches to dealing with plants first imported to the U.S. Between the 3D glasses that are required to appreciate the photographs, the layers of performance, and the histories that each photograph invokes, there’s a lot going on. However, Cortez’s research reveals that reality can be as absurd as fiction, as with the story of aquatic hyacinth plants deliberately imported to the U.S., then declared an “invasive species” whose spread authorities tried to curb through the relocation of hippopotami. In the same room, Guatemalan artist Esvin Alarcón Lam’s Injerto [Graft], is an installation pointing towards the history of botanical expeditions and the movement of plant species such as bamboo as well as the proliferation of at times–Orientalist imagery, but unwittingly also draws attention to the politics of transferring plants into white-cube exhibition spaces, and to the history of Asian migration and immigrant communities across the region, including in Panama.

It is in Raíces (Roots, 2015), a series of photographs of performances by Guatemalan artist Regina José Galindo, that these ideas are conveyed most powerfully, synthetically, and effectively, yielding one of the most arresting pieces in Mesotrópicos. Installed as a grid of 3×7, each picture shows a different figure, man or woman, lying belly-down on the ground, on grassy beds or dirt. Their arms appear startlingly truncated. Upon closer observation, it becomes clear that they are buried in the soil, hugging the large roots of trees. The wall text explains that these are all immigrants whom she photographed in Italy, embracing the roots of trees with whom they share a place of origin. Their performances are made only more powerful by the awareness that such a view, of bodies on the ground with arms as if cut off, corresponds to more gruesome visions which Central Americans were used to seeing for decades. It is in the reclaiming of this visual language that Raíces so powerfully transcends.

Some works, at least in their presentation, miss out on the opportunity to speak to such complexity. Inés Verdugo’s photographs of sugar bricks pocked with holes carved by insects, the remnants of a house structure she built from them, feel too removed, too clean against their seamless white background. They miss out on the opportunity to speak of the complex historical narratives embedded in the gesture of building a house from sugar. Whose house? Whose sugar? Whose labor? I wished for a more generous form of documentation of the artist’s intervention.

Other works that lingered in my memory include Donna Conlon’s Black Mold (2021), whose delicate ink drawings of black mold stood out for their simplicity and delicacy. Exhibited in light wood frames without glass, these works on paper speak directly to material deterioration while allowing the possibility of their own decay. Guatemalan artist Andrea Monroy’s textiles, splattered with a natural dye that looks like blood, allude to centuries-long textile practices among indigenous groups, especially women, but also to the many cycles of violence they have endured. Tony Cruz-Pabón’s animation Nube de azúcar shows a figure walking, covered in scraggly undefined objects that slowly untether and fly away. Are they clouds? Plastic bags? Dead bodies? Wares for sale? The weight off one’s shoulders? With simplicity of means, this animation captures qualities of contingency omnipresent in Central American urban centers. Installed in a corner up high in a dark room, it also feels like stumbling on a secret.

Mesotrópicos prompts reflection on the links between our natural environments and colonial histories, how these have shaped the present cultural moment and continue to inflect and hamper the struggles for socioeconomic and gender-based equality as well as environmental justice. Well into the second year of the pandemic it also serves as a reminder of the powerful effect of seeing multidimensional artworks placed into conversation with each other, and of a strong curatorial vision unfold in off-screen space.

Tamara Diaz Bringas, “La primera guerra de las bananas. MESóTICA II / Centroamérica: re-generación,” textos errantes (blog), July 9, 2019, https://wp.me/p5EwDS-fK

Comments

There are no coments available.