01.02.2019

By Juan P. Fernández

Oaxaca, México

November 4, 2018 – February 5, 2019

The image repeats itself. It is an encounter. The snake and the dog look at each other. The corn seeds shelter. Questions emerge; however, we seek to avoid deductions. We’re in Oaxaca, the city of resistance—or so it has been called since 2006. Layers of paint accumulate on the walls; the palimpsest goes on. I turn around the corner and find myself again standing before the image. I stop and analyze it. I read: HACER NOCHE. Arte contemporáneo del sur de África [Crossing Night. Contemporary Art of South Africa]. We have the elements. A wreck is upon us, the transatlantic nears in. The archive of memory is activated. In Oaxaca, and in Mexico in general, one cannot break away from the colonial ”legacy”, whose wound lives on: racism, exploitation, dispossession, ecocide… It’s a part of the scenery, the context in which the exhibition is embedded. Crossing Night is an initiative by Idris Naim A.C. and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes of Mexico, organized by Francisco Berzunza (general coordinator), Peet Pienaar, Ery Camara, Josh Ginsburg, Paloma Porraz, Michael Tymbios and Darío Yazbek Bernal. Through a program of exhibitions and residencies, Crossing Night gathers artists from South Africa in a Mexican cultural context.

This type of South-South encounters bear the potential to generate critical reflection from the perspective of the art system, and are the ideal framework to elaborate pending compartencias. In other words, they are platforms to go beyond recurring and hegemonic discourses on contemporary art, where valuable and iconoclastic dialogues can be generated through the prism of the encounter and the sharedness of distant geographies.

The dog meets the snake on a ring of corn

When looking at the venue management, the show is a symbolic paradox: two former Colonial convents (Dominican, 16th century) introduce decolonial critical narratives at its heart. It’s an impressive image which leads us to a breaking point. The wedge is nailed. The crack is widened. What next?

The spaces where most part of the Crossing Night exhibition program is held momentarily are the Centro Cultural Santo Domingo—which belongs to the state—and the privately-owned Centro Cultural San Pablo. The real paradox, however, lies in the appropriation undertaken by the organizers of former instruments of conquest which are today refurbished witnesses of an unclosed chapter in history, which society aims to forget. This is significant to understand the potentialities of some of the works exhibited, beyond obvious criteria like discipline and aesthetics. When relating the works in the show to what these venues represent, a prajñā of sorts may emerge, a sense of cognitive acuity that might set us free from pending traumas.

The viewpoint from which I address the curatorial discourse of Crossing Night, if we are to look past the concepts developed in the works on view, is the common or underlying distance. That is to say, a position that assesses the free and subjective space of reflection that codifies every being in their individual phenomenal experience, added to their psychohistorical one. This distance of thinking activates our own experience and transforms it into knowledge in use.

To avoid the obstacles of its bureaucracy, to walk its halls, to trangress the institution and its symbolic spaces are but steps leading to the encounter. We are inside. The wall reads: The dead are not underground… the dead are not dead. The sentence, belonging to Birago Diop [Le souffle des ancêtres, 1960] is a statement that functions both as an epigraph and exhibition text, saying all there is to say.

Dan Halter’s work, la venganza de 400 años está perdiendo sus dientes de leche [the 400 years revenge is losing its baby teeth] (2018) is a call to action, a humor-filled diplomatic act. A corn cob loses its grain, winks at us. The national identity is dislocated in its foundations. I think of the migrations, the forced exchanges (or displacements?) or teocintle to corn. The seeds symbolically set to balance everything out, to do justice, to break ground. The essay repeats itself. The appropriations become mutual.

In the series of drawings Mgodoyi 5 (1993) by David Koloane, the dogs don’t bark. They look at us, represent us. From this territory, this work allows us to encounter the myth of that night journey through the Mictlán in company of the xoloitzcuintles: a transition. They ceased to embody oppression, refused to be the suburban pets of the apartheid. They abandon their leashes, no longer symbolize state violence, but now become our very reflection. They deambulate, sniff around, know the way, guide us.

We thus find ourselves with two tools in hand: the corn seeds and the dog. The empowerment continues; the absorption of the rite, the healing process. The corporal gesture, the internalized mudra [1], which connects us to the continuity of what is seemingly opposed, such as day and night, life and death, black and white.

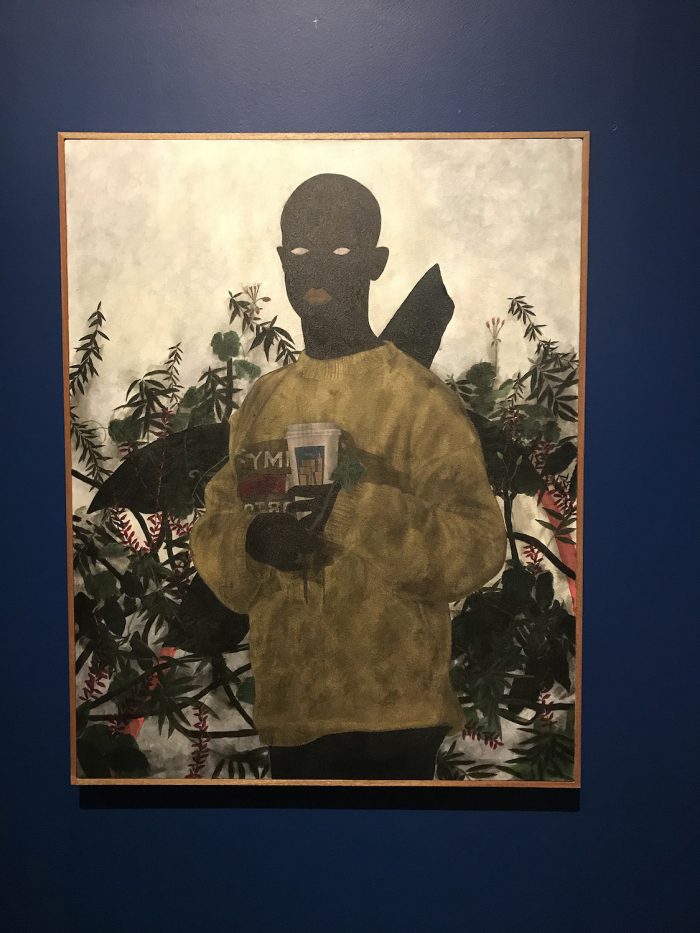

Changing identities as an act of resistance

The game of visibilities can be found in the Eyes Wide Shut (2001) photographs of Santu Mokofeng and Ziphelele, Parktown (2016) by Zanele Muholi, which complete and trace a line with the rejected portraits of Marlene Dumas [Rejects (1994 – ongoing)] and Sabelo Mlangeni’s veilings and saturations in In time, A morning after Umlindelo (2016). A mirror of kinds is unveiled, an intimate exchange of one for the other in the curatorial narrative. We cross the line, change, now find ourselves on the other side. We experience the resistance against the hegemonic, and are now able to recognize from the distance what it is to be socially invisible.

With a second skin like Xipe Tópec, experience is made anew, the narrative acquires new meaning and turns into a practical exercise of knowledge. We venture inside Samson Mudzunga’s big drum [Drum (1996)] inspired by the Venda traditions. We activate the ritual while touching it from within: order is restablished, lost lore returns, the nature of things is recovered, life and death occur simultaneously, are united, dualities vanish. We no longer seek to fragment, but rather assume this continuous transition.

Breaking point and symbolic appropriation, Mandela dead? Or the pineapple in cubes

What social values are shared collectively? How are they inherited and reproduced? The presence of Nelson Mukhuba with his piece Skeleton (1985) is highly symbolic in the exhibition, for the association with the end of his life, when he kills his family and burns his studio before committing suicide (1987), is inevitable. I believe a pertinent insight into the life and work of this artist can be reached through Fanon’s Black Skin, White Masks (1952) and its understanding of the feelings of despair, dependency and insufficiency evident in the personality and behavior of black people in a context of white oppression, where the only visible path leads to an appropriation of the cultural codes of the colonizer.

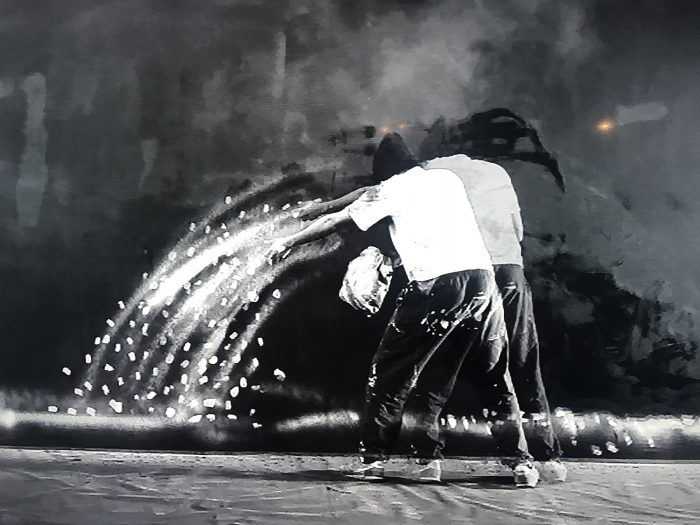

The history of collective brutality narrated in the first person told by Penny Siopis in her film Communion (2011) tells us not only of the transgression and defiance to the imposed order, but also of a series of symptoms produced by the institution of a system of oppression. The fact is that this kind of stories are not only recurrent in Mexico and South Africa periodically. The question is anything but new: What are the possibilities of art beyond the aesthetic appropriation and the symbolic reproduction of a fact or situation? This is to say, what remains after representation? How are the exceeding subjectivities put into use? What is their function?

Cosmic Interlude Orbit

The spectres of apartheid and neoliberal oppression sprout once again and feed the narratives and discourses of contemporary artists of recent generations, such as Kemag Wa Lehulere and Robin Rhode, whose works defy exoticisms and geographies, making them relatable and useful. Black boards, chalk and overwriting symbolize the transitional aspect of history. The installation is enclosed with the gaze of porcelain dogs, laying in a submissive position on the remains of desks, as if awaiting orders in obedience. The classroom is deconstructed in Cosmic Interlude Orbit (2016) by Kemag Wa Lehulere. The piece is a critique of the education systems, Western knowledge and collective amnesia seen in oppressed societies, such as colonized territories.

This ends as it begins, with light, in Robin Rhode’s Harvest (2005). An animation that relates to the epigraphs of this text and Dan Halter’s opening piece, the corn seeds and their potentialities. To germinate, flourish, break the ground, displace hegemonies, activate our components, de-fragment ourselves.

—

* Crossing night / Hacer noche is a large-scale exhibition and an initiative by Idris Naim A.C. and the Instituto Nacional de Bellas Artes of Mexico. The residency program began on October 1, 2018 and the openings were held in various venues in Oaxaca from November 4-10, 2018. This project is supported by Fundación Alfredo Harp Helú, the A4 Art Foundation (South Africa), the Asociación de Amigos del IAGO, and the Centro Fotográfico Manuel Álvarez Bravo and the Secretaría de las Culturas y las Artes del Estado de Oaxaca. More information on the organizers’ website: http://www.idrisnaim.com

Within the dharmic traditions such as Buddhism, a mudra is a sacred gesture generally performed with the hands, there is a variety of mudras, each one with different qualities, usually used in ritual sessions or meditation.

Comments

There are no coments available.