09.09.2021

”The exhibition is an open, urgent, and ongoing dialogue that echoes local claims and those of individuals, communities, and neighboring nations in the face of the climate crisis, the food crisis, the loss of knowledge, the destruction of ecosystems and species, and the continuation of colonial relations, among others.”

When I was a child, my grandfather taught me there is a knowledge based on observation and attention to nature. Thus, I learned that the appearance of winged ants shortly after the sunset, the increase in the intensity of the frogs’ croaking, the chirping of crickets, and even the cows grouping together and throwing themselves to cover the dry grass, are signs that anticipate rain. It is the same as the swallows fluttering in circles or the female yagrumo showing the luminous side of its leaves. I was born in the Caribbean, so I also learned that mango and avocado trees are hurricane indicators that almost never fail when they are full of fruit.

From the entrance of the exhibition; the silkscreen prints belonging to the series Doppler Landscapes (2109) by Guillermo Rodríguez, the installation Serpent River Book & Serpent Table (2017) by Carolina Caycedo, and el tejido a mano Silat (2020) by the Thañí group, invite us to reflect on the element of water with representations based on meteorology, hydrography, mythology, and craftsmanship. Later, this invitation is also extended by Guiddo Yanitto with his video Hacer agua (2012) and Amara Abdal with Proyecto Tierrafiltra, a living workshop that seeks to create a water filter with Puerto Rican resources and land. Both address concerns about the attainment of the element, or the making of it; ominous symbols of a future of scarcity.

Nevertheless, it is necessary to clarify that in this post-hurricane Puerto Rico, or at the time of the yagrumo, important self-managed, individual, collective, and community projects have germinated, which continue to position themselves, exploring and educating about sustainable practices and solidarity with the environment even from the point of view of art.

It is pleasing to say that the questioning and counterproposals from the creative and artistic production to the forms of development and evolution of the present, without ignoring the imaginaries of the future, are a constant giving pulse to the exhibition.

And this is also its achievement in and from a country in bankruptcy, almost privatized, full of ruins, and vulnerable to climate change; a country where museums, knowledge-generating institutions that must be in tune with the realities of the places where they exist, have been timid in participating, joining or making visible the community and collective struggles with all their nuances and the role of the artists in them.

Not far from this, surprisingly inside one of the rooms of the exhibition, a huge Cayuco (2019) is presented. This is the result of the research and dissemination project Canoas, cayucos y balsas undertaken by Engel Leonardo on Antillean navigation and the knowledge derived from it regarding the indigenous people and descendants of the region.

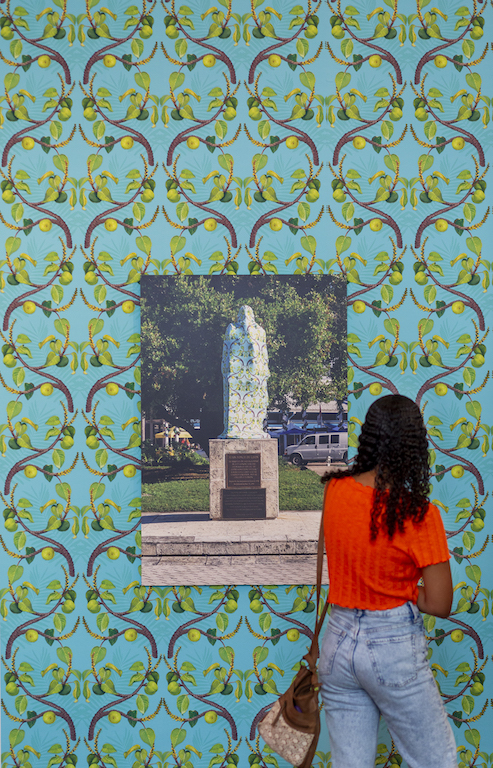

Finally, looking at decolonization, emancipation, and freedom as the hopeful path that the exhibition places before the eyes of its visitors, I must mention the tropical prints and photographs of Joiri Minaya’s in the series Encumbramientos (2019-2021), and Femme Minotaur (2021) by Cristina Tufiño.

As an action and response to the colonial and patriarchal past exalted in monuments still standing, Minaya—using ethnobotany and redefining them—covers them with floral-printed fabrics used by native, Black, and Afro-Caribbean people for healing, casting out evil spirits and protection. The yagrumo, also known by metathesis as grayumo, appears in them. Tufiño’s sculpture of a minotaur with feminine forms—as reflected in the title, sitting on a piece of a pigmented oak trunk that fell during Hurricane Maria—is a sort of monument-homage to her grandmother, family, and matriarchal power. It is striking that the sculpture made of bare clay seems at times to be observing and at others, it seems only to remain serenely in the present moment, perhaps growing or germinating like a yagrumo on something high up that also collapsed.

And then, my grandfather’s reminder: “Everything will change, so it’s important to be in tune with the earth.”

—

El momento del yagrumo

Museo de Arte Contemporáneo de Puerto Rico, San Juan, Puerto Rico

May 30 to September 19, 2021

Curated by Marina Reyes Franco

Participating artists: Allora & Calzadilla in collaboration with Ted Chiang, Alice Chéverez, Amara Abdal Figueroa, Carolina Caycedo, Guido Yannitto, Grupo Thañí accompanied by Guido Yannitto, Cristina Tufiño, Daniel Lind Ramos, El Departamento de la Comida, Engel Leonardo, Evarista “Varín” Chéverez Díaz, Guillermo E. Rodríguez, Javier Orfón, Joiri Minaya, Karla Sofía Claudio Betancourt, Marilyn Boror Bor, Natalia Ortega Gámez, Ramiro Chaves, Ricardo Ariel Toribio, and Ursula Biemann & Paulo Tavares.

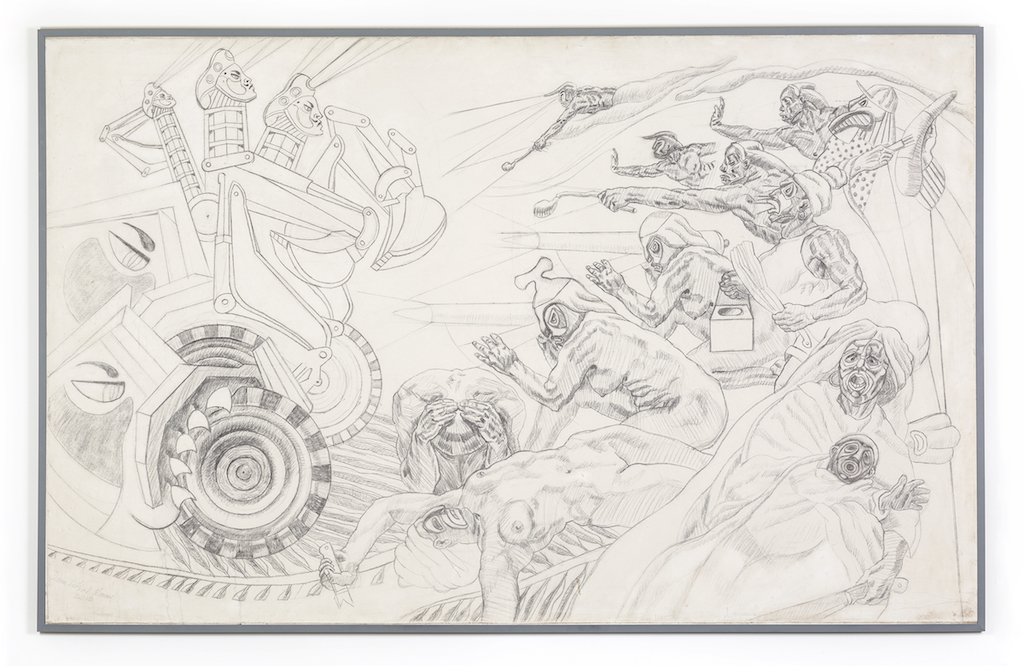

The scene refers directly to the murder of Adolfina Villanueva at the hands of the Puerto Rican Police on February 6th, 1980. It took place in Loíza, a coastal municipality in the northeastern part of the country that was a place of indigenous and maroon settlements that still preserves and celebrates the roots of its Afro-descendant population. As Lind Ramos depicts, Adolfina died during the eviction of her house by a landowner, accompanied by the police squad and road rollers.

Comments

There are no coments available.