15.11.2020

Angélica Chávez Blanco reflects on the cultural policies of the state of Chihuahua, in the north of Mexico, to open questions about their relationship with independent projects in the field of contemporary art that exercise the awareness of the commons in that context.

Before

Peoples of land, barbarians, arid, end of culture,

desert, border, indigenous, industries, nomads,

missions, mines, province.

Nowadays it is complex to talk about cultural policies in Mexico as something suitable, right or wrong. We cannot deny that historically the State, from its federal government to the municipal governments, reinforces social and cultural models based on structures of inequality. More than 70 years have passed since the UNESCO Universal Declaration of Human Rights was signed by Mexico, a country considered the regional vanguard in the signing of agreements, treaties and laws for the defense of these rights. Even so, there are critical scenarios that we must address and reflect.

In the particular case of the state of Chihuahua, we have passed through government models that have positioned culture from a patrimonialist and elitist vision as a reinforcement of social privileges and hegemonic power structures, such as museums or historical monuments. Currently, public policy is based on the Plan Estatal de Desarrollo [State Development Plan], and on cultural issues, on the Programa Sectorial de Cultura 2017-2021 [Sectoral Culture Program 2017-2021]. These plans propose a model of governance, which, unlike the previous government model, suggests a more dynamic mechanism subject to regulations that provide legal support for democratic participation mechanisms in which cultural agents can participate in the design of cultural policies. This model of governance has made it possible to articulate cultural policies between the statewide, private and civil spheres by breaking down the social, political and cultural boundaries of the state population.

However, in spite of these transformations, cultural policies have not managed to cover needs such as the working conditions of the artistic and cultural community, the sustainability of projects or the diversification of support to other sectors. From this perspective, for governments culture represents an expense rather than a right, since from their capitalist logic it is difficult to measure or verify its impact.

Cultural policies require new concepts, methodologies and inputs that allow for flexibility on questions such as: Is cultural action accessible and for whom? Does this make any biographical sense to the people who inhabit this territory? What is the current use of cultural spaces? Do artistic communities know and exercise their cultural rights? What is the socio-political force that the artists exercise? What are the current dialogues between cultural agents and the government? Are new challenges and needs being contemplated according to our time?

It would be necessary to reflect carefully on the possible answers. The truth is that we cannot continue to understand cultural policies in the same way as ten years ago, nor can we continue to standardize their design criteria from a centralist viewpoint. We would then have to rethink from an intersectional perspective how to coordinate between the different sectors in order to reduce the inequality gaps that will come from the massification, technologization and global democratization of culture in the current framework of national and geopolitical rethinking, as is the case with the so-called 4T as well as the signing of the T-MEC.

Probably the first step would be to accept that there is a crisis of cultural representation and that in order to address this crisis it is necessary to demystify the political discourses on democratization, participation and decentralization of cultural goods and services, or what governance proposes as “guaranteeing cultural rights”. What can be done so that these discourses do not only serve as institutional legitimization and really make way for organizations or communities with the capacity to influence the public and cultural problems of their environment? Is it possible to rethink these capitalist practices that lead us to reason in such an individualistic way from art or cultural production? I believe that in Mexico there is a great cultural resistance and the north, because of its rugged geography,[1] has been as well. I would therefore advocate for cultural policies where governments stimulate the generation of common resources so that communities of art and culture workers can collectively develop and sustain their own cultural infrastructures.

Particularly in the field of contemporary art, it is important to observe and take care of the way independent projects are built, since some of these productions are also shaped according to the trends that institutions, the market or digital reproduction dictate. For this reason, not only governments are responsible for creating this relevance within cultural policy, but art workers must also commit to critical exercises on the socio-political impact of our projects in order to take responsibility for their public dimension.

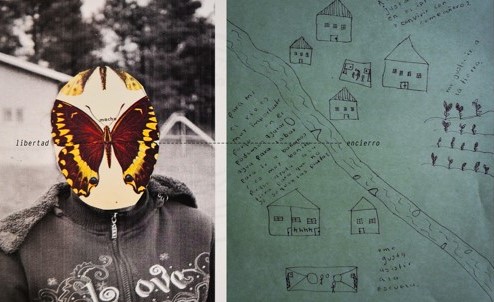

Personally, I find power in the production of contemporary art from the collective and communal processes, for in them exists the possibility of consuming, producing, remixing, thinking and living culture in a full and communal way. I am interested in narrative practices, participatory or intersectional art, horizontal and communal processes of resistance. In this sense, there are various Chihuahua artists who have made an effort and work from these perspectives in order to recover symbolic elements from our context and for our context. Somehow these projects, which illustrate this text, are influencing the strategies that cultural institutions propose to reach sectors that had not been addressed, for example, from the municipal dimension to the particularity of the maquiladora industries and indigenous communities. However, I would like to leave the space open to critical analysis of these proposals and to generate a dialogue about them.

Finally, carrying out these critical exercises implies discussing, questioning, demanding and proposing collectively to create projects that provide necessary, dignified and pertinent conditions for people to generate self-management and symbolic recovery links as well as free and active access: their own interpretation of their cultural geography as a testing ground and exploration of options.

Now

Resisting the industry, rethinking maquila,

Displaced persons, migrants, border crossers, dissidents, provincials.

Our creations are the liminal space to resist

We are at the border, in the contact zone.

The culture does not end where the barbeque begins, Vasconcelos.

The state of Chihuahua is made up of an enormous geographic diversity: mountains, plains and desert. The extreme climate, the distances and the difficulty of access to the communities make this area very rugged.

Comments

There are no coments available.