09.08.2020

The series of opinions around cultural policies of the Mexican government regarding a public cultural system in crisis continues, for which Oliver Terrones questions the current centralism that limits any guild possibility in contrast to his experience in Acapulco, Guerrero through the “Cultura Comunitaria” program, thus evidencing contradictions rarely recognized in the discussion.

Erasure, Corrective Art, Drugs, and Cultural Policies: Are We Ready for This Conversation?

Mexico’s debate on cultural policies does not belong solely to a unionized group of a specific art and certain culture. To think of such debate in this way is to reduce it to the occupational interests of just one section. It is not, also, a competition only for those who live off of subsidies and trust funds nor a debate in which the only participants are the country’s three most populated cities or a university’s art museum. Perhaps a centralized, urban guild that considers itself a country’s sole and most important cultural producer should not be in charge of deciding said country’s cultural policies.

A key term within cultural rights is cultural life. In Mexico, we have policies and structures that erase or inhibit the cultural life of certain sectors through extractivist efforts and/or the promotion of artistic, historical, cultural, moral, and aesthetic values that depreciate cultural manifestations, circuits, and dynamics that are outside of the center. In the case of Mexico, this debate goes beyond “high” and “low” culture.

Within this guild, similarly to those groups whose cultural life is inhibited by existing power structures, those who lack the stereotypical “artist” persona—for example, workers that find themselves under the supervision and care (or, more appropriately, oversight and neglect) of the Mexican Ministry of Culture—are also seen as less. No less curious is certain artists’ aversion to consider themselves workers of art and culture. If we have artists that refuse to consider themselves art and cultural workers, therefore preventing this from becoming a worker’s conflict, then what type of conflict is it?

In Mexico there exists a naturalized, colonial, and centralist historical/commercial narrative in which the center dictates and underwrites culture and reduces the rest to a homogenous province, omitting and erasing peripheral productions, circuits, and dynamics, thinking us mere consumers of the praised and produced by the center’s whiteness. It is of utmost urgency, then, to underscore the structures that perpetuate such inequality and what public institutions do or stop doing to maintain said structures. Not being able to pursue a cultural life of one’s own often is accompanied by other social problems, such as access to health care and housing and the negation of basic human rights. If this debate was only about art, we would not have to talk about all this, but as long national public policies are in the picture, this must enter the conversation.

What actions has the Mexican government taken to guarantee the pursuit of cultural rights? Up until now, Cultura Comunitaria seems to be its most developed program that pretends to accelerate and decelerate certain processes under the premise of decentralization of culture, which in turn pretended to advance the decentralization of other public administration sectors but, as is apparent until now, actually has not happened nor is ever going to happen. This program’s conflicts are so varied and of such wide scope that I cannot begin to explain them in one text; I am confident that they can be unearthed in time and by more people. Let us go then go back to the initial question of who are—or who have to be—the beneficiaries of cultural policies in Mexico for the pursuit of their own cultural life.

This past first of July, a team of armed commandos attacked a rehabilitation center—colloquially known as an “annex”—in Irapuato, Guanajuato. They massacred 27 people. In Mexico, rehabilitation centers are often privatized and are not always operated legally or under the supervision of healthcare professionals. I mention this only to highlight conflicts in cultural policies stemming from the question: how does the idea of art serve as a tool for “reconverting” or “reprogramming” a social group?

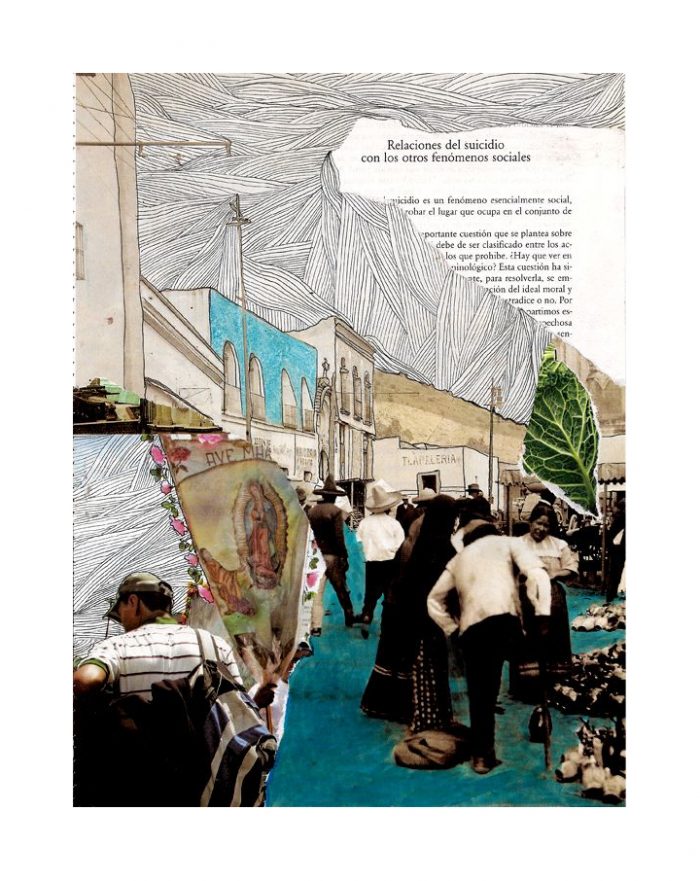

In December of 2019, I was called upon by the program Juntos por la paz [Together for Peace] for an “exercise for the connection between axes” of the program Cultura Comunitaria in Ciudad Renacimiento, one of the neighborhoods with the highest insecurity indexes in Acapulco, Guerrero. Said activity consisted in giving a three-hour art workshop planned only a week in advance, oriented towards fighting and preventing addiction. Concerned that they thought that art could, in three hours, prevent and fight addiction and before clarifying that, because of obvious logistical barriers I could not work any miracles nor ensure that someone would stop consuming psychoactive substances during that time, I accepted. I proposed that I could only outline sociocultural imaginaries in relation to addiction and psychoactive substances, and from there, elucidate more questions than answers. I asked for materials and, with the excuse of austerity, they offered me office supplies and photocopies. Beyond the evident logistical problems, it was expected that I convince a group to stop consuming psychoactives with just one lecture—something outside of any realm of possibility, and certainly, outside of art’s realm of possibility. I seriously wondered if the person who directed this did it out of naivety or another cause. To reduce the gravity of the omissions, they told me that the workshop would only be a discussion with the attendee’s children; and so, this was no longer addiction prevention, but a daycare. After reaching that point, I no longer understood the premises of the program nor the objectives of the express-addiction-prevention workshop; the only process that seemed to be well planned and thought out was the execution of a propagandistic event in which, after taking a photograph, one could say: We are working for peace, preventing addictions in one of Acapulco’s most dangerous neighborhoods. I refused. Days after, I saw photographs of the event featuring smiling helpers (certainly strangers to Ciudad Renacimiento), and I never learned if someone was able to leave drugs or alcohol after those two hours. I suspect it never was so.

Can art be a tool to prevent addiction and the consumption of psychoactive substances? I assume that many readers laugh at the thought of the sheer quantity of alcohol and psychoactive substances that are consumed in dynamics associated with art. I mention this not because said consumption is necessarily associated with or inherent to art, nor because I am trying to criminalize or encourage said consumption. It is simply an exercise in comparison: while we try to prevent a marginalized group from Acapulco’s periphery to consume psychoactive substances through an art workshop, for another group, art does not have this corrective or preventive function, nor will they consume or produce it under such premises. Why are some groups attempted to be corrected or prevented from delinquent conduct through an art workshop and others are not? And, when the discourse says that we all have a right to make art, is this what is being referred to?

Is this the work of art? No, and this is exactly what I have been trying to explain from the start.

Comments

There are no coments available.