04.05.2019

By Albeley Rodríguez-Bencomo

January 23, 2019 – May 26, 2019

Amarillo, azul y roto. Años 90: arte y crisis en Ecuador [Yellow, Blue and Broken. The 90s: Art and Crisis in Ecuador], whose title alludes to the Ecuadorian tricolor flag, as a symbol of the torn, interrupted nation, is an exhibition that is presented at the Centro de Arte Contemporáneo (CAC) of Quito until May 26, 2019. The curatorial discourse was developed by two practicing artists, who also happen to be visual anthropologists, teachers and researchers of the Visual Arts Degree of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador (PUCE): Pamela Cevallos and Manuel Kingman.

The framework of this curatorship is supported by a thorough investigation of more than five years of dedication—with the support of the PUCE during three years—by its authors. Through this inquiry, approximations from various angles were made in relation to the conformation of “the contemporary” in the Ecuador of the twentieth century’s nineties, the transformations and ruptures caused by the various dimensions of the crisis of those years, the links with the Ecuadorian artists, the works that they produced around that same decade, as well as the dissertations carried out in dialogue and discussion with other researchers of the field, from which the coming publication of the book Modernidad y contemporaneidad: arte ecuatoriano en la década de 1990 [Modernity and Contemporaneity: Ecuadorian Art in the Decade of 1990] was born, same that compiles twelve essays.

The nineties were characterized by the fall of the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union, also by the entry of fierce neoliberal policies that produced a profound socio-economic shock on the international scene. But, additionally, policies of apparent amplitude towards the cultural heterogeneities and the deceitful erasure of the frontiers in favor of the globalization process anchored to international agreements and treaties came to redraw the geopolitics through the commercial.

In Latin America, while commemorating the 500th anniversary of the “discovery of America”—the scar of the modern/colonial project in this geography visible through the aforementioned neoliberal projects—, several countries, such as Venezuela and Argentina, experienced thunderous economic disasters caused by financial crises, which plagued the region of convulsive changes.

In the Ecuadorian case, the context was discouraging. The crisis unleashed twenty years ago by the Feriado bancario [Bank Holiday]—as it was known in Ecuador—of March 1999 gathered a precedent process of invisible financial debacle that brought as consequences the economic setback of the majority of the Ecuadorian population; bringing with it the largest exodus of Ecuadorians ever experienced in the history of the country, the disappearance of the Sucre—the national currency—, dollarization, and, in the face of great socioeconomic instability, important uprisings of various indigenous peoples, street agitations and the expulsion of several presidents from their seats.

Looking through the lens offered by Amarillo, azul y roto, the reality of the Ecuadorian art field revealed the absence of an institutional framework that would accommodate the new manifestations of art, the arrival of alternative spaces, and a growing break with respect to the media originating from the fine arts, through the emergence of proposals of performance, video art, installations and other artistic languages and practices, as well as an expanded conception of traditional media. But, above all, the widespread irritation gave way to a determined political involvement of individuals and artistic collectives in the production of questioning discourses, and at the same time unusually creative, all of which this exhibition reveals very clearly.

Without title, two expository chapters, arranged in the pavilions 3 and 4 of the CAC, organize the exhibition by approaching it with different aspects. In one of them, Pavilion 3, the proposal Banderita Tricolor (1999) by the artists Manuela Rivadeneira and Nelson García, who formed the company Artes No Decorativas S.A., relates the call extended by that “company” to various artists to reflect different positions in relation to the Ecuadorian flag. This piece is presented in the exhibition, with an elaborate load of cynicism that the artists showed then, through video art, and a generous archive material arranged in glass cases where, among other documents, the legal record, published in the press, of that company that was as much of a ghost as the companies that cheated the Ecuador of those years.

Likewise, in the woodcut engravings: 121 honorables y otras atrocidades (1999), Juan Pablo Ordóñez recalls the action in which the Cuenca artist offered, at an irresistible price, a—symbolic—market of deputies, through the repeated image of a faceless subject wearing a tie, with the splendid smile of a politician, made without ink and barely visible, which narrates the ease with which they came to buy consciences in the Ecuadorian Congress. Both artistic strategies used institutional frameworks to carry out their proposals, whilst unveiling the mechanisms used to cover up the acts of corruption that forged the crisis in their country with their legal records.

A documentary video by Alberto Muenala, shows the historical value of the mobilization carried out in 1992, in which eight thousand indigenous people, from different towns, arrive in Quito from Pastaza, after having walked 500 kilometers to present their claims for progress and an independent education, as well as a decentralized administration. It is a moving video with a unique aesthetic value that accounts for the determination of several organized cultural groups and their ability to be heard.

This video has as companion, in its anteroom, an exceptional graphic of the trajectory of the eminent Ecuadorian artist Pilar Flores, who joined the complaint for the forced disappearance of the Restrepo brothers that occurred during the presidency of León Febres-Cordero in 1988. The powerful image collected by Flores from the mother of these brothers, Luz Elena Arizmendi, along with the phrase Por nuestros niños hasta la vida [For our children for life], later became the emblem of other manifestations in memory of the disappeared.

After the examples mentioned in this chapter of Amarillo, azul y roto, I will summarize the intention of the curatorial discourse for the Pavilion 3, with an approach that allows us to recognize the events of the time, from a group that obeys the need to make visible those politicized questions before the speeches of power and the nation, the corruption, the protests by the disappeared people, the demand for respecting human rights, and the transforming indigenous risings.

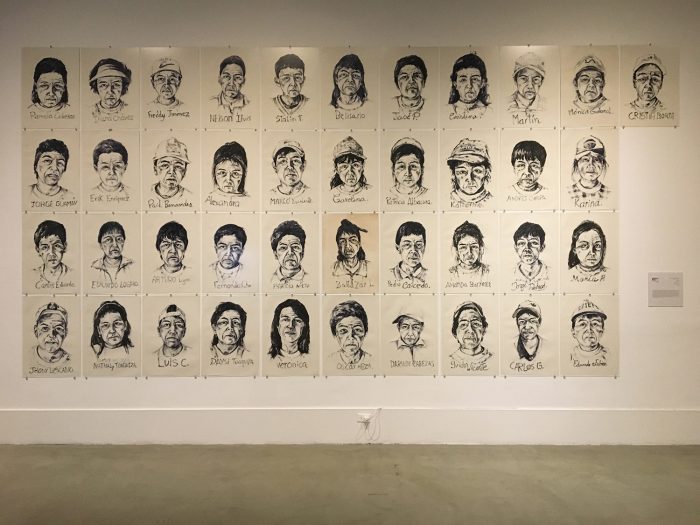

In the other pavilion, Pavilion 4, works such as Marco Alvarado’s Aprendiendo de los maestros (2001) are presented. An extraordinary piece, loaded with corrosive and erudite humor, playing with appropriationism, to point out the faces of corrupt bankers—Alvarado mockingly calls them masters—who “appropriated” the financial capital of the Ecuadorians. Marco Alvarado appropriates the strategies used by paradigmatic artists of contemporary art—Barbara Kruger, Marcel Duchamp, Cindy Sherman, Andy Warhol—to portray with their language the faces of those bankers.

The video recording of the performance Hasta la vista baby (2000), by Ana Fernández, recounts the disappearance of the Sucre, the national currency that existed since 1884. This action consisted in carrying out a funeral march on the day when the Sucre ceased to be the official currency of Ecuador (September 9, 2000). Fernández was at the head, acting as the Sucre. The march managed to gather with great symbolic efficiency the suffering and indignant experience of the Ecuadorians—numerous artists and inhabitants of Quito—who, throughout the circuit, washed the flag and expressed themselves through singing, crying, laughter and shouting.

The proposals of Pavilion 4 are shown to revisit more humorous approaches, and to relate the new ties of the Ecuadorian art with the public space and the unofficial spaces that, in the context of the crisis, were opened from the autonomous administrations.

Both nuclei can be explored as a hilarious narrative of the Ecuadorian crisis of the nineties, a sensitive narrative but, sometimes, carried out with fine humor, which is woven from that tragic experience that has apparently been overcome.

The exhibition makes it possible to assess the importance of several pieces that had not been publicly appreciated, for they could never be exhibited before, as well as an over-all vision that builds a little explored narrative of the Ecuadorian reality of the crisis years and its becoming.

The exhibition, furthermore, boasts the quality that each of the selected pieces is accompanied by a story that contextualizes them in detail, both from its artistic value and from its relation to the moment under discussion.

This is an exhibition whose importance is not limited only to the Ecuadorian borders—in which the faces of that moment, like that of former President Jamil Mahuad, have reappeared in the current political landscape, while the Waoranis have achieved a ruling in favor of the defense of their territories, and against the extractive policies—, but it allows to read economic, cultural, social and political phenomena that, far from being mere matter of a recent past, function as a wake-up call on the similarities and contrasts with our present, in all of present-day Latin America, where the tensions of the crises deployed by neoliberal policies, conservative and sharply obituaries, are the order of the day.

Quito, April 29th, 2019

Comments

There are no coments available.