14.06.2021

Miguel Imbaquingo, co-founder of Tawna Films, reflects on the colonial gaze that has left its mark on the memory of the Ecuadorian Amazonian peoples and on the little resemblance to their reality. He thus proposes using the seventh art for the region to produce their own cinema as one more way of self-determination.

Runakuna wañushkata

wiñay kawsaymi rimanchi.

Llankashkakuna wañushkata

kapchiymi rimanchi.

Kay chikannaya wanchina butanikata.

kallari kawsaymi rimanchik.

— Chris Marker

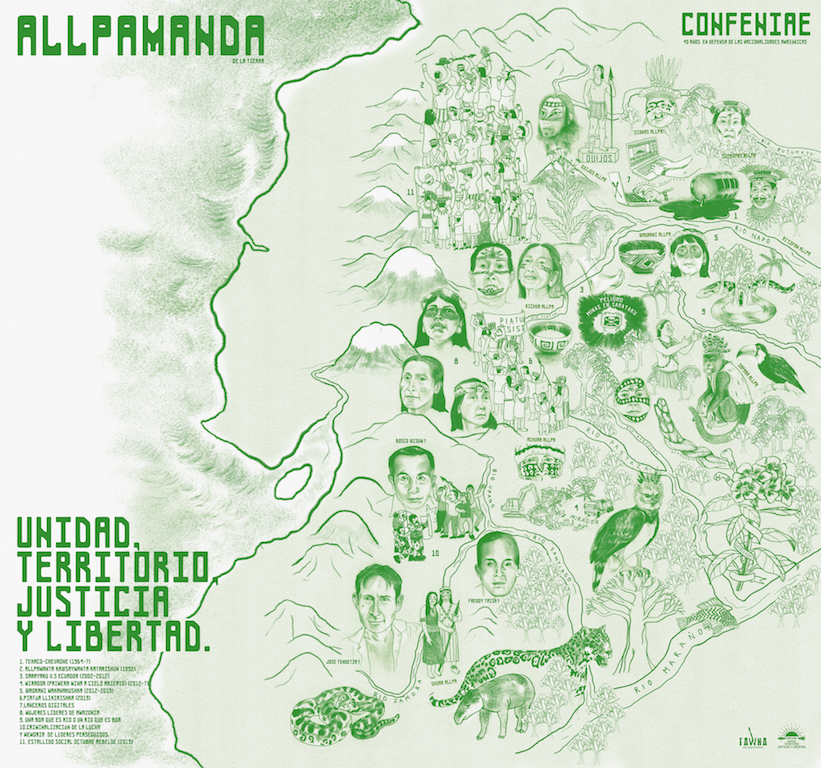

Currently, the majority of Indigenous peoples of the Ecuadorian Amazon live scattered in remote jungle areas, which means that we possess a large portion of the world’s existing biodiversity. The Ecuadorian Amazon is home to 11 nations which identify as Indigenous peoples, each of which has its own language and culture.

Our first approach to orality occurs in the family, through language learning. Knowledge is acquired through communication and oral transmission using the building blocks of learning: images, sounds, dreams, and language.

Tawna: Cine desde Territorio proposes the construction of its own way of looking, to produce audiovisual narratives from a different mode of thinking. It aims to decolonize knowledge and propose alternative ways of filmmaking that can serve as tools of communication producing representation and self-representation out of political, aesthetic, and cultural resistance. We want our perspective to generate a distinct form of filmmaking, a cinema in which we cease to be objects and become subjects with our own voices.

Representation through Otherness has been one of the many ways we have been oppressed and stigmatized through our portrayal in film.

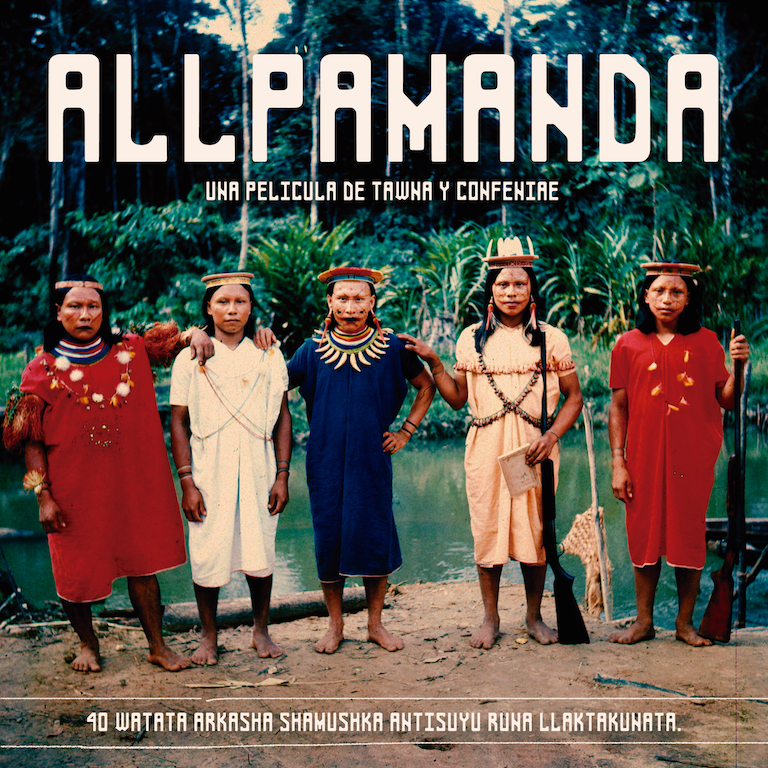

We didn’t have the opportunity to represent ourselves with dignity or decide how we wanted to be represented to society. An example of this is the film Los Invencibles Shuaras del Alto Amazonas [The Invincible Shuaras of the High Amazon], directed by Carlos Crespi in 1926. Considered to be the first indigenist film made in Ecuador, it presented the world of the Indinegous peoples from the perspective of the director’s gaze.

The young people of today’s Amazonian communities question the imaginary that has been imposed upon us, rejecting the gaze through which we continue to be perceived and through which we continue to be colonized by means of the same cinema of exotic images and ethnographic perspectives of our people, of our grandfathers and grandmothers. We believe that it is possible to break this gaze by making our own audiovisual productions, our own cinema from the land. A self-critical, rebellious, experimental cinema that is, above all, in our own language.

Among our people, orality is the underpinning of our word, as now we hope cinema from the land will be. This argument should be understood as a response to the claim that video cannot substitute orality. The concept of orality is the existing space out of which we can develop our own meaning and the significance of regional content; it does not solely entail methods of transmission or transmitted content, but also includes the very mechanisms through which and within which both are constructed and developed, as well as their uses. Cinema and orality complement each other in the transmission of culture, the defense of the social struggles of our Indigenous peoples, and the safekeeping of their historical memory.

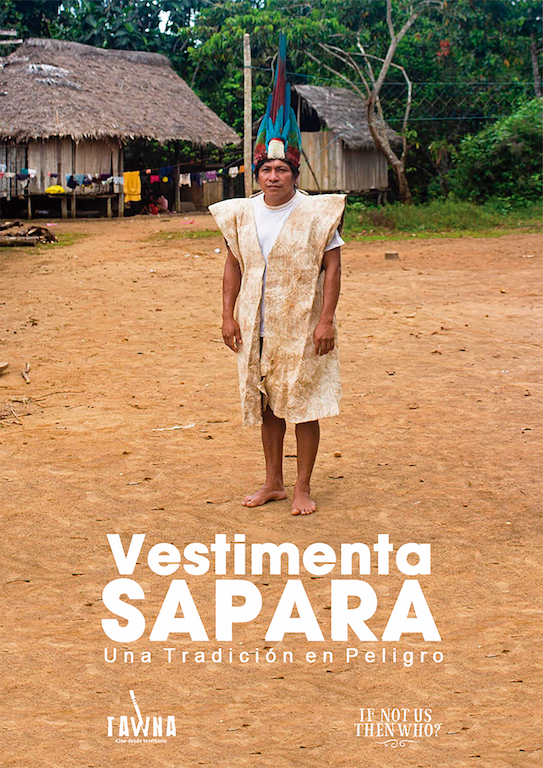

Though a recent development, the acquisition of cinematographic techniques as another tool of audiovisual communication for the peoples and nations of the Amazon has revolutionized the transmission of ideas within communities in the Amazon to make the fight in our land visible. The extractivist policy of the Ecuadorian state towards the Amazon where our Indigenous nations live has, over the course of hundreds of years, unleashed historic struggles in defense of our ancestral land. Among the fights to protect the freedom of our jungle are those of the Kichwa people of Sarayaku against the state, those of the Piatúa Kichwas against hydroelectric companies, that of the Nankinst against the Chinese miners, and that of the Sápara Nation in opposition to the oil concessions in their territory. These fights have received international attention and have become examples for other Latin American peoples and nations. In contrast to state-distributed “information,” the audiovisual records that have followed the struggles of the peoples and nations have served to demonstrate the truth about what has happened and continues to happen in our land. Cinema has been fundamental in making these conflicts and resistance visible and has been a means of continuing the cultural heritage of orality without losing touch with the historical roots of our Indigenous peoples.

Therefore, film is a fundamental anchor in the process of reviving our cultural networks and territorial resistance. Many different forms of audiovisual aesthetics have been developed in order to keep attention on our memories and on the fight for our land.

We can name several documentaries made in the Amazon that have been instrumental in our resistance struggle: Los descendientes del Jaguar [The Descendants of the Jaguar] by documentary filmmaker Eriberto Gualinga; Allpamanta Hatarishun Kawsaymanta [For Land and Life, Let Us Rise] by Alberto Muenala; Piatúa Resiste [Piatúa Resists] by Yanda Inayu y Miguel Imbaquingo. All of these are audiovisual works that have generated political and social responses in the country. Furthermore, at Tawna we are currently in the process of registering our next films Allpamanta, Tsitsanu, and Sachama kuti tikrana, which is a challenge for us—continuing to build ourselves through audiovisual narratives.

The debates about the definition of cinema from our peoples and nations have always been open and continue to be a point of contention, principally because they are considered from an academic perspective—a perspective and cinematographic gaze that does not understand the context and realities of the peoples and nations of the Amazon.

It should also be noted that these perspectives continue to be used in the majority of productions that come out of this region putting labels on our audiovisual production from the land.

The cinema produced by Indigenous peoples does not enjoy access to the same spaces of dissemination, nor is it included in the same privileged cultural and artistic arenas as the main official programming of the country’s film festivals. This ensures that our directors and stars are kept at the margins.

Another important characteristic of resistance that cinema from the land engages with is the production of work in our own language directed at our own communities where the films are made. In this way we are able to continue our oral tradition, appropriating the contemporary languages of sound and video in order to do so. These audiovisual productions respond to our own forms of communication and interpretation that grow out of our syncretisms and worldviews. Acceptance of such terms as “Indigenous directors” or “Indigenous cinema” reflects how others who have inhabited this intercultural and pluriverse society from colonization look at us.

In any case, to conclude this analysis of cinema from the land, it is important to reflect on the need to continue generating discomfort without expecting hypothetical academics to speak for us. Introducing our own politically and aesthetically impactful initiative into the cultural world strikes us as an interesting challenge for the cinematographic production of the peoples and nations of the Amazon. That is to say, let us continue to weave together and feed our self-representations with the rebellious colors of our own visuality and sonority.

Land autonomy and self-determination!

Here, from our shores opposed to the representation of the Amazon, landscape becomes home, and the static past is a living memory revitalized with the passage of time.

Chay ukumanta shamunchi, kunanka ñukanchi llankaykunata rikuchinata munanchi. Rurashkanchi tukuy runakuna sinchi hatarisha paktakta yachasha shamushkakunamanta, shinallata ñukanchi runa malta warmikuna kaymanta ñukanchi runakuna yuyaykunata, medio audiovisualpi allichisha sakinata munanchi.

El “otro” es la mirada hegemónica de les realizadores hacia nosotres, desde sus puntos de vista de la representación de nuestros elementos simbólicos y sincretismos que han interpretado y presentado a occidente desde sus propios sistemas de representaciones.

Comments

There are no coments available.