25.07.2022

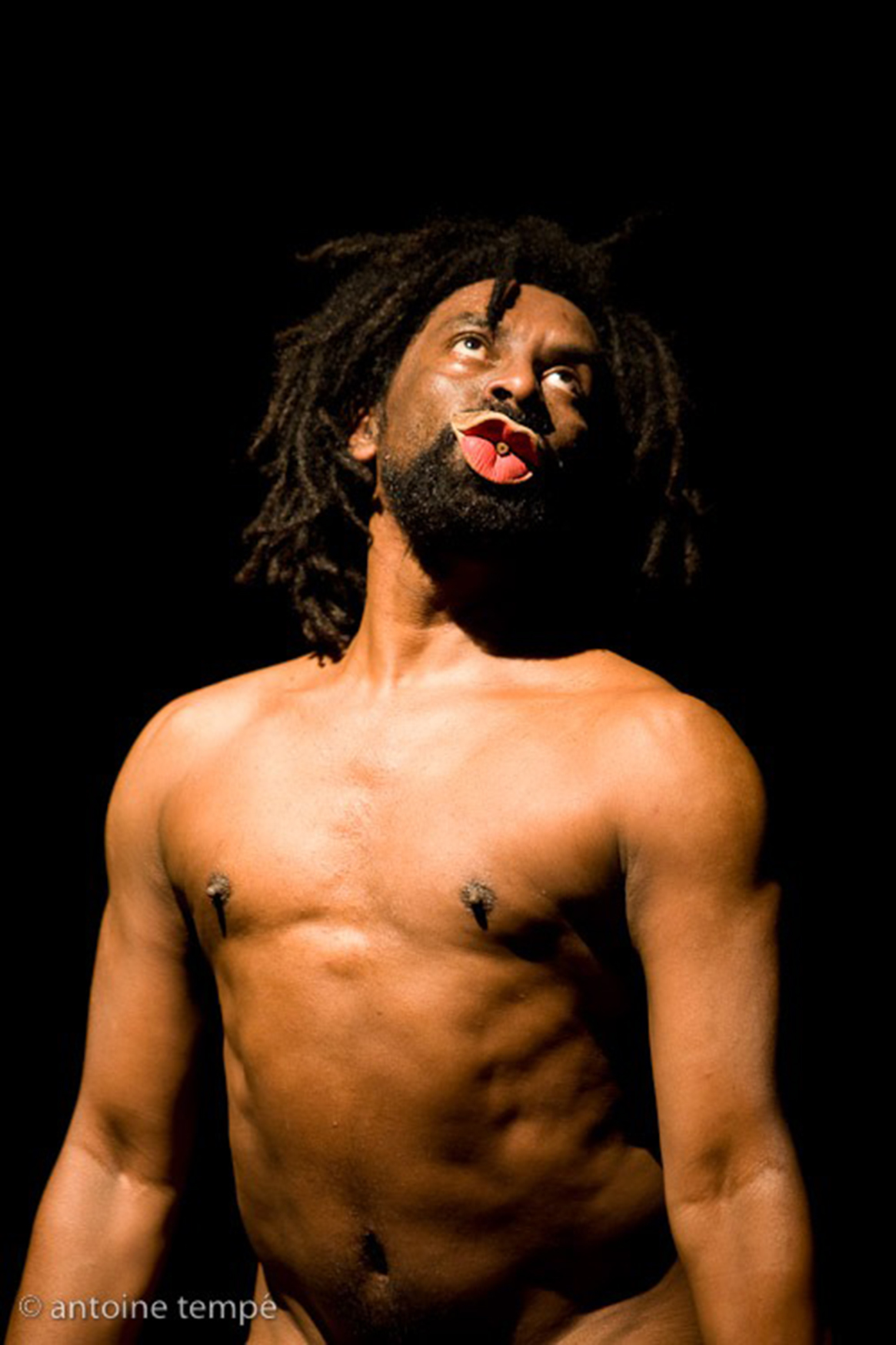

Pleasure, cosmoperception and black wandering, a choreographic essay

Introduction – Beatriz Lemos

If there is an erohistoriography of the dissident body, it is probably through movement and wandering. By refusing colonial imprisonment, we travel routes in order to share certain secrets. Thus, some exchanges are only possible between us. Only between us. Determined, we are.

The union of our desire is one of those secrets shared along the routes. And it is then that we understand that eroticism has to do with freedom.

To talk to Luiz de Abreu is to traverse this path, or rather, it is to walk while dancing, creating randomly precise or Cartesianly loose movements. It is to experience, between sensibility and reason, the challenge of the new, witnessing the reinvention of a body.

Our meeting starts with an editorial provocation made by Terremoto and, thus, it continued up to this point, dodging time, technology, deprivation, imagining for us the possibilities of wandering that have not yet been tested. Because if we are going to cross the tide, let it be with affection, let it be to meet again. And there is (almost) nothing more veiled, more taboo or silenced, than speaking and practicing autognosis on the autonomy of desire.

For many years, Luiz de Abreu’s art has been helping us to understand the fantasy of race from the perspective of the erotic and the traps that racism imposes on Black bodies. It is a body of work that confronts racist legacy head-on as a mechanism that exposes the codes of power structurally present in Brazilian society. Therefore, the conversation between Luiz and I arises in our lives as an invitation to reflect on pleasure beyond racial trauma. In doing so, I think we are able to imagine escape routes that make freedom possible.

If there is an erohistoriography of the dissident body, it is probably through movement and wandering.

Even in contemporary dance, where we aim to work in a non-colonial place of the body, the eye remains the leader of the creative process.

This body that sees beyond the eyes, that thinks beyond reason and finds its own ways to escape the traps of manipulation, is the same body that carries a memory of times that are not ours. Times past and times to come. A memory that dwells among organs, arms, and legs. In the film Ôrí, historian Beatriz Nascimento says that the Black body in dance will always be the liberated body. And so in the candomblé ceremonies as well, because when the orisha[1] dances, they summon the freedom of an entire people. Do you believe in an ancestral memory of movement? I understand that escape is a latent state that guides our bodies. But is there something like an inheritance that goes from a gestural repertoire to respiratory frequencies or body temperatures, that drives or pulses racialized bodies?

All Black bodies in the diaspora come from the same experience of slavery. Transformed into an object and dehumanized, it creates forms of resistance, for it is a repository of memory, a library of Black knowledge. It is in this body that all our knowledge resides. It is this body, constantly translated and transformed, that creates other Africas. Thus, thinking in the field of African religions, which are made of dance, music, animism, and not only of a concept of the divine, the body is necessary in all its powers to connect with the orisha and the entities. And gestural memory is derived from there.

The Black body of the city is always alert and in a state of dilation. I have spoken of this body in a constant state of performance as a political action. This is how I situate myself in the world.

This gestural memory of escape is transmitted from generation to generation. To be a Black body walking down the street, for example, it is necessary to know certain strategies and codes that show through appropriate clothing, the slowest and most harmonious gestures, good looks, haircuts, and nowadays, walking with a Bible under your arm. Everything is like a choreographic composition of daily life that has as dramaturgy a survival manual for the Black body.

This body that sees beyond the eyes, that thinks beyond reason and finds its own ways to escape the traps of manipulation, is the same body that carries a memory of times that are not ours. Times past and times to come.

Lately I have been thinking a lot about the right to desire, especially the discernment of desire. How stimuli act in our body and promote the potency of life—or rather, the life drive itself. And because they are so fundamental, they are intrinsically related to self-knowledge and the politics of conscience. When I bring up the right to discernment, I am referring to the mechanisms of control that forcibly induce subjectivities that deviate from the norm of social codes of conduct, idealizations of society, family, work, love, the functions of a body, etc. Lastly, do we desire what we really want to desire?

About 20 years ago I went to an exhibition in São Paulo of African pieces from a German museum. There, I saw a statue of Shango with breasts. It was a male and female body. Sometime later, I went to Germany and was able to visit this same museum, where I also found Peruvian, Mexican, and African pieces. I arrived at a place where there was a one-meter-long African boat. The museum security asked me if I wanted to touch the boat. So I did. There I could feel the DNA of my ancestors. And I could only feel it because of the white security guard’s permission. As I walked through the museum, I saw a picture of some Englishmen with their feet on top of a trunk containing gold, diamonds, and African art pieces. I asked the curator, “Did Germany steal these African pieces?” And he replied, “No. We did not steal them. We bought them from the British.”

Returning to the statue of Shango, that masculine and feminine Shango, I kept thinking about that idea of the body that was stolen, bought, and expropriated by the colonizers. But that statue of Shango tells me that there are other possibilities and other ideals of the body, sexuality , gender, eroticism, and sexual potency. Other ideals of the human, which constructs multiple body configurations to reinvent desires.

Orishas are ancestors who have been deified.

Comments

There are no coments available.