Issue 14: Look Who's Talking - Costa Rica Guatemala Nicaragua

Patricia Belli, Miguel A. López

Reading time: 12 minutes

08.04.2019

Curator Miguel A. López and the artist Patricia Belli make a critical and historical review of Belli’s artistic productions in order to recognize and reflect on the powers of art as the axis of mediation and discussion among agents within the dizzying contexts that Latin America goes through, as well as elucidate what effective resistance can mean today.

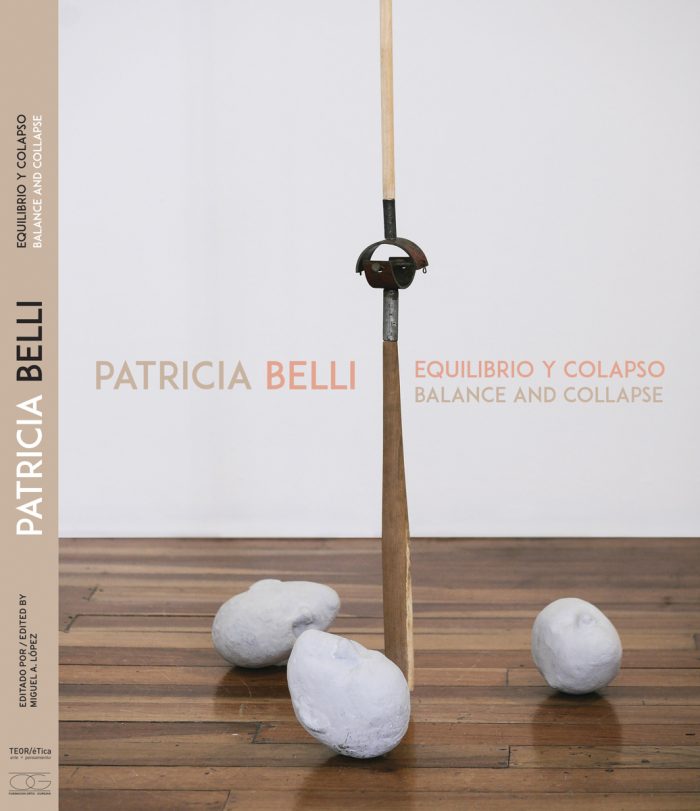

The presentation of the monographic book Patricia Belli: Balance and Collapse in December 2018 marked the closing of a three-year research project promoted by TEOR/éTica (San José, Costa Rica) around the work of artist and educator Patricia Belli (Managua, 1964). The project was the first of a TEOR/éTica initiative dedicated to review and document the trajectory of women artists who have transformed contemporary art in Central America. In addition to the book, it involved an anthological exhibition and the organization of its photographic archive that traveled through three countries. Belli has been one of Nicaragua’s critical art engines since the mid-eighties. Her work claims the power of the vulnerable body, but also its rage and libidinal energy, as authentic forms of resistance.

Miguel A. López: We just presented the book Patricia Belli: Balance and Collapse that accompanies the anthological exhibition of your work, which I had the privilege of curating. After Costa Rica, the exhibition traveled to Fundación Ortiz Gurdian (Nicaragua) and Fundación Paiz (Guatemala) during 2016 and 2017. This process allowed us to explore not only the complexity of your work that emerged in the mid-eighties but also the difficult processes of war and political conflict that the his- tory of Nicaragua has been through. What did this exhaustive review of your work mean to you?

Patricia Belli: It has been very beneficial. I can see more clearly where I want to go and what mistakes I do not want to repeat. I see my early work and feel a need to return to the exploration of myself, my emotions, the unconscious, and the symbols. Those times of adolescence and youth were beautiful, artistically speaking. My life was an emotional disaster and art—or creativity—was my refuge and healing. Then, almost two decades ago, I was putting distance between my intimate processes and what I was saying. That is, when I felt I had clearer things to say—not just things to feel and materialize—I started to change my strategy involuntarily.

Now I feel that the pretense of objectivity is a dress that does not fit me. I want to immerse myself in my fantasies and honor the scared and exiled girl of the world that I was. That also implies resisting contemporary aesthetics, the logic of ‘less is more’ and the idea that formal solutions have to be not only effective but efficient. I want to allow for processes focused on the discovery before the search for products.

MAL: In a context like Nicaragua, where the artistic infrastructure is so fragile, it is difficult to generate instances that allow us to study and make visible the important contributions of numerous artists. There are many outstanding debts, many necessary revisions, but few resources and spaces. What stories do you consider important that can be narrated?

We need to listen to each other to open the way to transformation.

PB: Just because of the causes you mention—the lack of publications and re- search—I feel that I do not really know Nicaraguan art in depth. What I can say are my wishes based on my limited information. As you know, in Nicaragua it has been prioritized to study artistic practices that echo the Western avant-garde movements, and even these, although they have been recognized, have not been sufficiently discussed or theorized. But the situation is even more serious when thinking about other artistic manifestations such as so-called “primitivism,” a self-taught painting style that emerged mainly in the Solentiname Islands with the accompaniment of Ernesto Cardenal. These works in the seventies and eighties enjoyed enormous popularity and were a currency of the Sandinista revolution. This is still minimally studied. Likewise, the woodcuts by María Gallo during the 1980s or the watercolors by María Lourdes Centeno since the 1970s are far from achieving the attention and analysis they deserve. The situation is different with recent contemporary art that, although we know better, is not really the subject of complex discussions.

I would love to know, before the history of art in Nicaragua, the stories of the artists, because making the decision to be an artist in this country as a life project is an immense thing. Although there are many clichés, bohemian, and machismos, there also was—and there is—nobility, convictions, intelligence, and poetry. I would say, these are more developed than the artistic production itself, and It would be nice to know more about these.

MAL: Based on what you mention, what motivates you to continue with an artistic exercise in the context of Nicaragua? From that, what concordance, correspondence, or relationship does this individual motivation find in the artistic communities of the Central American localities where your exhibition took place? Taking into account that the region is marked by fragmentation and poor collaboration between institutions in each country.

PB: I am from Nicaragua, and I live there. It’s not that I have alternatives, but I do not imagine living elsewhere, without the presence of black humor and Nicaraguan frankness. Even the cultural traumas—like our wars and the colony—are stories that shape us and that I consider important for conscious creativity.

My exhibition went through three countries, mine, Costa Rica and Guatemala. I know a little about the artistic communities of the three capital cities, Managua, San José, and Guatemala City, because Space for Research and Artistic Reflection (EspIRA), which I started almost 20 years ago, has worked with artists from all over the region. Your question forces me to generalize and reduce my perceptions about these artistic communities, which is an interesting exercise. They are—we are—obviously communities that reflect their respective societies.

San José is the farthest of all for me, not in emotional terms, but in terms of its production. Its—relatively— broad community of artists weaves discourses that in many cases are linked to globalization or speak of the nation-state, questioning or discarding its causes and effects. Guatemalan artists, for their part, treat these and other issues by passing them through the holes of their wounds: Guatemalan art is very visceral, or very sad. In Nicaragua we have similar concerns—adding the Sandinista Revolution as another great protagonist—but, in addition to passing the issues through the wounds, we also laugh a lot.

The three communities have very different dimensions, and the Nicaraguan is the smallest by far. Here, there is no degree in plastic or visual arts, and I think that has resulted in a lack of technical skills that in turn generate a disinterest in the trade. This is no small thing because, on the one hand, it limits the execution of certain ideas, but, on the other, it unfolds in languages that do not bind to any discipline and that generate an important conceptual freedom. It also generates a dirty, poor, and cheerful aesthetic that is quite sui generis.

That said, I have to emphasize that the artistic communities of the three cities have very strong emotional ties, achieved by decades of exchanges. These ties are not alien to the idiosyncratic coincidences of small postcolonial cities and the generalized urgency of configuring ourselves as our own centers and overcoming the complexities of the periphery. Certainly, the collaboration between institutions is scarce, but the relationships between the artists feed on themselves and achieve some results that, little by little, change the panorama and our own gaze towards ourselves.

The policy of repression and persecution of the government of Ortega and Murillo has included hundreds of dead and missing, numerous arbitrary arrests, and much intimidation against citizens, the media and human rights defenders.

MAL: Curatorial operations that respond to local emergencies also have a global impact, which means affecting at different scales the ways in which the narratives of the present are being configured. After the exhibition, you were invited to EVA International in Ireland and then commissioned new work for the 10th Berlin Biennial, We Do Not Need Another Hero, under the general curatorship of Gabi Ncgobo, your work in Berlin incorporated your experience associated with the repression of the government of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo (current leaders of the Sandinista National Liberation Front) against citizen protests in Nicaragua in April 2018. How was that process?

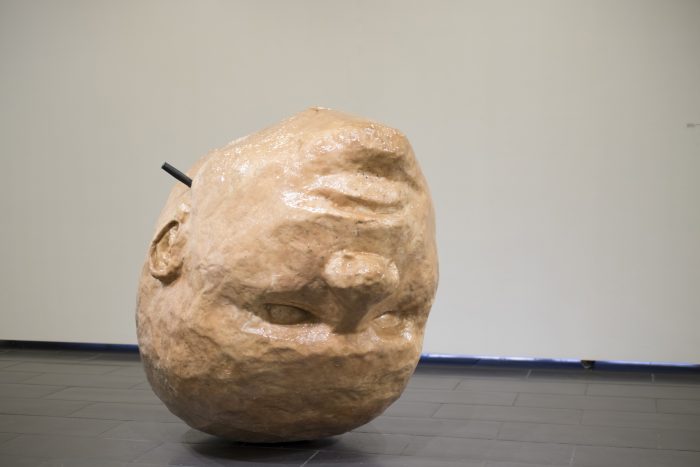

PB: The curator Gabi Ncgobo asked me to propose a new work for the Berlin Biennial to exhibit it along with some historical pieces of mine from the nineties. For this, I presented Unbalanced, which meant five months of work. They are some sculptures with audios downloaded from the internet that collect moments of the excesses of this government in a murderous dictatorship. What seems important to me is not to expose the facts—because journalists do this better—, but to create, through real audios (speeches by leaders, shouts from people in the street, ripped voices claiming rights, and other more abstract sounds), tensed emotional lines between the governmental arrogance and cynicism, outrage, lament, and fear, without sentimentality but with emotional forcefulness.

Presenting this work in Berlin needed an introductory paragraph to mention the situation in my country, because very little was known outside of Nicaragua about what was happening. Even to a European audience, Nicaragua may sound like an abstract term. That’s why the tone and texture of the voices are the map. When you join with those wobbly heads on the floor, it generates a sordid atmosphere that also involves the public in the initial gesture of kicking them. So, even if the public does not speak Spanish, sensations and emotions build violence. Maybe it was a scream in the desert, but it was a necessary cry for me and for someone interested to come and listen. This was also the most ambitious project I have faced in material and technological terms (12 fiberglass heads with electronic audio systems), not counting the emotional tax associated with the fact of processing that horrendous period of repression in Nicaragua. The work helped me understand the horror we were going through.

This installation also allowed me to understand the sculptures with molds of heads that I had been working on for the last three years, whose first appearance was Porfiadas (2015). The technique of counterbalanced heads—that returned to the original place after being moved or impacted—in Berlin became something else: they were like soccer balls since they were activated when people kicked them or moved with their feet. There I knew better the meanings that these could detonate when, finally, they began to talk about death.

Participating in EVA International and the Berlin Biennial, or more recently the invitations I received for residencies in Mexico or Paris, are privileges that three years ago, before the exhibition and the book, I could not have imagined. A different channel of communication has been opened. It scares me a little because I feel it reduces the margin of error, of trial and play. They are sudden changes in the scale of production and I am barely in the process of learning to manage them and articulate them with my desires and fears.

MAL: I want to dwell a little more on the political situation in Nicaragua. Between the first presentation of the exhibition, in 2016, and the launch of the book, in 2018, things changed drastically. The policy of repression and persecution of the government of Ortega and Murillo has included hundreds of dead and missing, numerous arbitrary arrests, and much intimidation against citizens, the media and human rights defenders. The impunity of all this has installed a climate of frustration and impotence in the Nicaraguan population. In general, I believe that Latin America is going through a very difficult moment where democratic frameworks are profoundly weakened. How do you think the perception of your work changes in this new context?

PB: Yes, things have changed a lot. The mechanisms of violent repression in Nicaragua were imposed as state policy in April 2018, and their constant change of tactics keeps us in terror and in suspense. In that context, the appreciation not only of my work but of art in general has been completely transformed. At first, the pain and stupor were very intense, and the emotional response of the population was like a generalized sense of nonsense that obviously embraced art. Before the threat, death, danger, vulnerability, injustice, there was no room for complex reflections because it was necessary to respond immediately—that is, with pints, posters, and clear and solid slogans. It was not appropriate to sow anxieties but to shout truths. In that context, the metaphorical and contemplative world of my work became extremely untimely. Foolish even.

When the murders of the first months decreased, the sudden pain was giving way to other forms of suffering, indignation, and struggle. In that framework, the ideas of balance and collapse became again relevant. Some of my works were updated to the letter, as in the case of Porfiadas, in which instability and violence are alive and respond to human actions. I feel that the hardness of the context was installed in the works themselves, as if something happened in them, almost premonitory, which perhaps announced this sinister end of the year. It is possible that everything will change again tomorrow.

MAL: Finally, I want to ask you about education, since one of your most important efforts in the last two decades has been to create experimental educational pro- grams like EspIRA, in Managua, that has allowed us to critically train new generations of artists in Central America. How does this political crisis force us to rethink the role of education and art?

PB: I am lucky to be able to answer this from a position that the crisis has strengthened. Still, I have been working with the EspIRA groups for years: the solution is dialogue. I say that I am lucky because this has been the tool that, within the association, has allowed us to face the crisis. It is part of the dialogue and leads to a dialogue. I’m not talking about consensus, but listening and sharing our emotional responses, interpretations, and explanations about things, be it about art or a popular uprising. This transcends education and art. It is a matter of human relationships; without dialogue, we lock ourselves in our individual gaze and deny others, even deny the others. We need to listen to each other to open the way to transformation.

Comments

There are no coments available.