07.03.2022

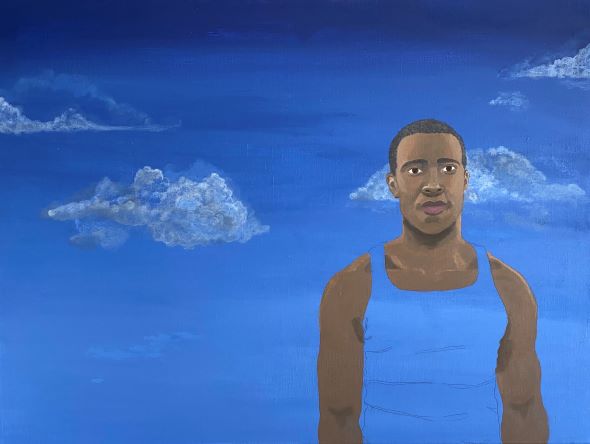

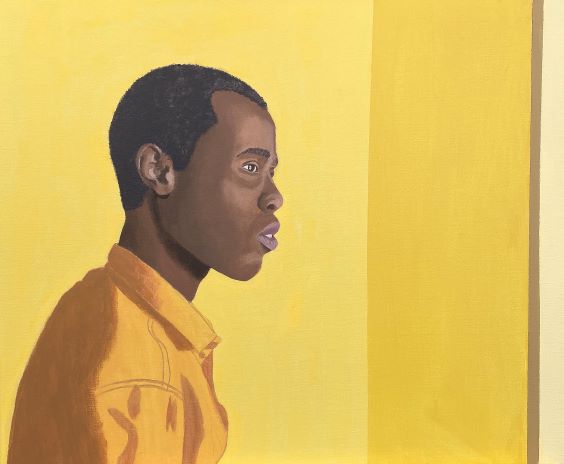

Nohora A. Arrieta approaches the work of Brazilian artist Tiago Sant’Ana with a question: what does it mean to be free, to be, completely, and thus being to open infinite horizons for our practice as critics or artists or writers?

1.

How many times have I died

in the longest night?

In the longest,

thickest and quietest night

how many times have I died

in the Calunga night?[1]

Tiago Sant’Ana was born in Santo Antônio de Jesus, in the Recôncavo Baiano, in 1990. Like several of the municipalities surrounding Baía de Todos-os-Santos, Santo Antônio de Jesus has a soil made of dark and clayey marzipan; sticky during the winter and dry in the summer, good for planting sugar cane. In Segredos Internos: engenhos e escravos na sociedade colonial (Intimate Secrets: Mills and Slaves in Colonial Society) (1988), Stuart Schwartz reports that in 1587 there were 36 sugar mills in operation in the region. It is said that at the beginning of the sixteenth century, Bahia was the second largest sugar producer in the territory which today is Brazil, only surpassed by the neighboring captaincy of Pernambuco, and that half of the population of Recôncavo were African slaves who worked in the plantations.

Sugar gave Recôncavo and Brazil their raison d’être. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Brazilian sociologist Gilberto Freyre described the plantation as the “origin of the nation.” In his essay Casa grande e Senzala (“Masters and Slaves”) (1933), he sets up the sugar plantation as the space that creates harmony between masters and enslaved. Intellectuals contemporary to Freyre, among them José Lins do Rego, author of the novels of the “sugarcane cycle,” contributed to the creation of a “nostalgia” for the plantation. In Menino de Engenho (Plantation Boy), Lins do Rego describes the sugar mill of his childhood as “a corner of heaven”.[2] This imaginary of the plantation lingers on not only in the texts of Freyre and José Lins do Rego, and in the picturesque illustrations of mills that might adorn the walls of a luxurious café in São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro.

The nostalgia for the plantation and the violence of its legacy live on in the illegal logging of agribusiness in the Brazilian Amazon and in the incursions of the military police in the favelas—in the politics of death.

2.

The night doesn’t pass

and I’m in it

dying again

and nameless again

Santo Antonio de Jesus, São Francisco do Conde, Cachoeira… The Recôncavo is strewn with the ruins of old sugar mills and the stories of lords with names such as Alexandre Gómes de Argolo, baron of Cajaíba, who is said to have thrown more than one rebellious slave into the sea alive so that the fish could feed on fresh meat. Tiago Sant’Ana grew up surrounded by those mills, their ruins and stories, and in 2017 he began a series of performances to interrogate them. Four of those performances, Refino #3, Refino #4, Passar em branco, and Açúcar sobre capela were presented in his first solo exhibition, Casa de Purgar, curated by Ayrson Heráclito at the Museu de arte da Bahia (Bahia Art Museum) in March 2018. Casa de purgar was the name of the room in the sugar mill where molasses was crystallized and “pure” or whiter sugar, which was exported, was divided from “impure” or muscovado sugar, which was consumed locally. Casa de purgar was shown for the second time at the Paço Imperial (Imperial Palace) in Rio de Janeiro in August 2018, and it was there that I saw it.

The declaration, which did not involve the inclusion of the Afro-descendant population in a national project, was quickly revealed to be a fragile freedom.

There is something of that fragility in the performances Passar em branco and Açúcar sobre capela. In the first, Sant’Ana irons a wrap of white cloth in the ruined room of a sugar mill. In the second, he covers the ruins of the chapel of the Paramirim sugar mill in São Francisco do Conde with 100 kilograms of sugar. The exhausted face, the ironing and sifting arms recall the slave labor without which Brazil would not exist. But almost every piece of art is an invocation of the present and Sant’Ana’s pieces are no exception; the allusion to slave labor also alludes to the precarious labor conditions the Afro-Brazilian population have suffered since the times of Isabel. The pieces inhabit a conceptual horizon that has been set out by black intellectuals: Clóvis Moura or Lélia Gonzalez have broken down the ways in which the mãe preta (the enslaved woman who took care of the masters’ children) or the mulatto woman were turned into characters in a plantation narrative that naturalized slave, domestic, and poorly paid jobs as the only labor option for Afro-Brazilians.[4] In Refino #1, Sant’Ana beats 100 tons of sugar to the point of exhaustion. In Refino #2, he sits in a room of an old sugar mill and is covered by 100 tons of sugar. In these performances, sugar exhausts or covers Sant’Ana’s body, and names the violence of a system and a country where a young black man is killed every 23 minutes.

Although Sant’Ana’s work can be read against the backdrop of the plantation experience as inherited by a black man, the truth is that the language proposed by his pieces intervenes into an entire national imaginary, one that has been inherited by all: colonial history, the slave past, what does it mean to be Brazilian? In Refino #3, Sant’Ana’s uses his hand to cover a page of a book bearing an image of three enslaved people moving a manual mill with sugar. The image is signed by Jean Baptiste Debret, a French traveler who lived in Brazil between 1816 and 1831 who portrayed the colonial daily life and the slave system often in a picturesque light. In Refino #4, the same hand wipes the sugar from the image, first slowly, then forcefully, almost desperately: how can we narrate the past in a way that acknowledges the wounds and instigates us to recognize ourselves, collectively, in it? How can we interrogate the archive in order to be? The poetic, oblique way in which Casa de Purgar returns to the plantation and its narratives ask questions that could suggest (collective) paths to escape.

3.

I have died so many times

but I am always reborn

even stronger

brave and beautiful

– being is all I know.

In the photographic series Sapatos de açúcar, Sant’Ana, dressed in white, wades into a river. In one of the photographs, the artist looks unperturbed at the camera while holding two shoes sculpted in sugar. In another, he completely submerges himself so that only the shoes are visible. The series builds a tension between the fragility of the shoes, which could disintegrate completely upon contact with water, and the fact that this minimal tragedy does not occur because Sant’Ana holds them up. It is in this (hopeful) tension that some pieces of Baixa dos Sapateiros acquire a poetic and liberating condition. The video Ao res do chão follows a group of Black men as they walk through the rooms of a colonial mansion. They are all barefoot, bare-chested, and each carries a pair of shoes on his shoulder. One could say that these men carry the fragility of being what they are in Brazil. But the final scene is a balm: each one abandons his pair of shoes and leaves the stage with a slow, determined, barefoot step, as if the precarious symbol of freedom (the shoes) were not necessary for what they, as Black men, can claim.

This and the other epigraphs are stanzas from the poem “Na noite Calunga, do bairro Cabula”, by the Afro-Brazilian poet Ricardo Alexio.

Gilberto Freyre, Casa grande e Senzala. Formação da familia brasileira sob o regime da economia patriarcal (Masters and Slaves: The Formation of the Brazilian Family under the Patriarchal Economy) (Recife: Gilberto Freyre Foundation, 2003); José Lins do Rego, Menino de engenho: romance (Plantation Boy: Novel) 27. ed. J. Olympio, [1940] 2012; Thomas Rogers, The Deepest Wounds: A Labor and Environmental History of Sugar in Northeast Brazil (University of North Carolina Press, 2010).

I frame my thinking about flight or escape in terms of the theories of maroonage proposed by Edouard Glissant, Kamau Bratwhaite, and other thinkers of the diaspora.

Clóvis Moura, Sociologia do Negro Brasileiro (Sociology of Black Brazilians) (São Paulo: Ática Publishing House, 1988); Lélia Gonzalez, “Racismo e sexismo na cultura brasileira” (“Racism and Sexism in Brazilian Culture”) Revista Ciências Sociais Hoje (Social Sciences Today Magazine), Anpocs (National Association of Graduate Studies and Research in Social Sciences) (1984); 223-244; Lélia Gonzalez, “A mulher negra na sociedade brasileira” (“The Black Woman in Brazilian Society”) in Madel T. Luz (Org.), O lugar da mulher: estudos sobre a condição feminina na sociedade atual (The Place of Women: Studies on the Status of Women in Today’s Society) (Rio de Janeiro: Edições Graal (Graal/Grail Editions), 1982).

Jota Mombaça proposes an illuminating discussion in this regard: “The Cognitive Plantation” Afterall, August 2020-January, 2021.

Robin D. G. Kelley, Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination (Beacon Press, 2003).

Comments

There are no coments available.