Issue 19: Planetary Solidarity - archive body language

Ana García Jácome, Jacobo Zambrano-Rangel, Minh Nguyen

Reading time: 9 minutes

16.11.2020

In conversation with the artist and researcher Ana García Jácome, writer Minh Nguyen and artist Jacobo Zambrano-Rangel discuss Jácome’s practice, the social construction of disability, comparative disability studies in México and abroad, reconceiving its historical and present-day conditions through art, and the possibility of solidarity across difference.

Earlier this year at Threewalls in Chicago, we convened a gathering called Colloquium Under a Palm Tree, where we invited participants to respond to what Cuban anthropologist Fernando Ortiz calls transculturation, or the complex exchange of cultural influences that results from colonial conquest. That evening, the artist Ana García Jácome, whose work focuses on theories and histories of disability in México and abroad, presented on her project It’s Like She Never Existed (2018 – ongoing). Tracing the hidden story of her aunt Coquis who had cerebral palsy, Jácome suggested that the exclusion of disabled people in family histories parallels exclusion in larger, institutional records of history.

When Terremoto approached us for this issue themed Planetary Solidarity, García Jácome came to our minds for a few reasons. For a start, her work expands disability discourse beyond its predominant loci in North America and the West, and additionally prods us to interrogate the conditions that generate such epistemes of knowledge. As for further elaboration, we invite you to read our conversation with García Jácome, in which we discuss her practice, the social model of disability, reimagining its historical and present-day conditions through art, and the possibilities of solidarity across cultural and geographic differences.

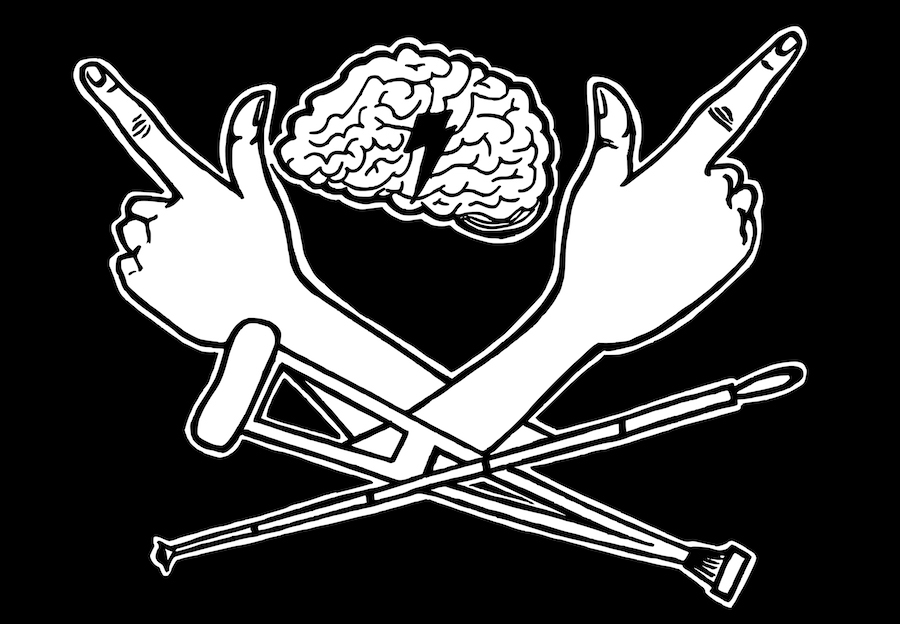

And the problem is not only about access, it extends to the widespread notion that the relationship between art and disability is only about therapy, that art serves as a cathartic outlet for people with disabilities. With that mindset, accessibility efforts become patronizing demonstrations of fake inclusion. Real access is a political stance that is concerned with the active participation of people with disabilities in the entire process: from production to dissemination, from research to consumption and criticism.

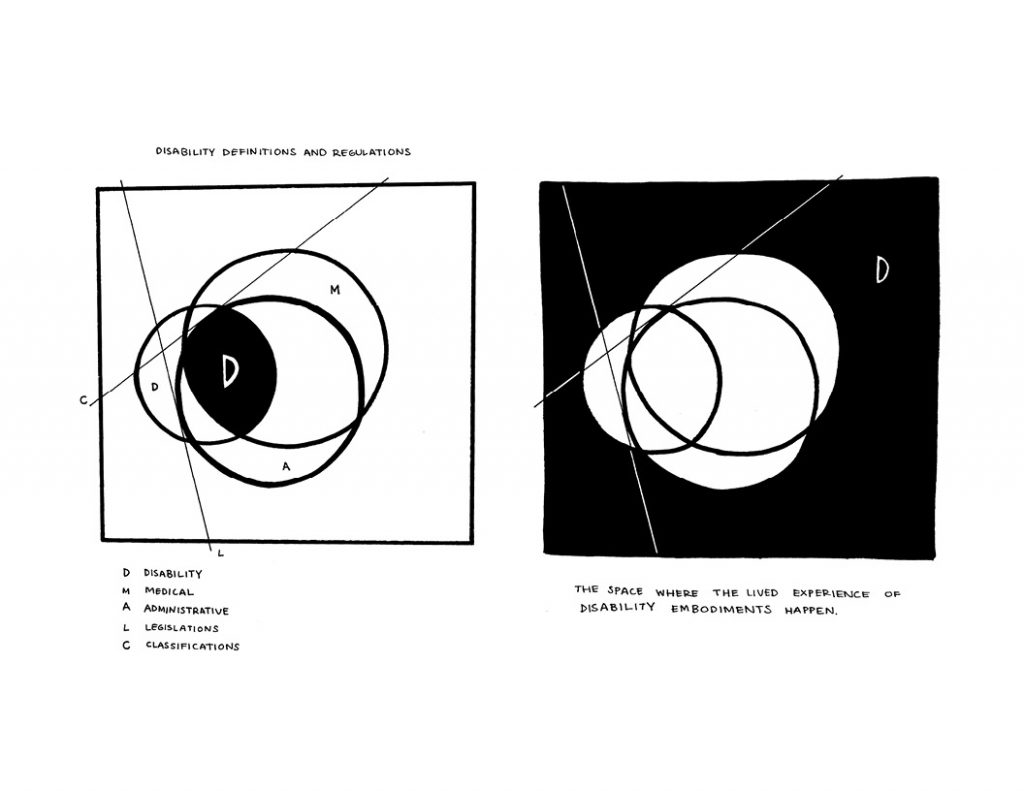

GJ: It’s important to understand the history of disability as a constellation, while also not dismissing the particularities of their specific locales. Semantic and conceptual shifts especially from imperial countries highly influence the language, knowledge and experiences of the colonized, so it’s important to stay grounded in one’s own territory. Let’s take crip and disca culture as an example: crip is the appropriation of crippled, a reclamation of a derogatory word used toward disabled people, turned into a tool for self-identification and community building. In México the word disca works similarly, sometimes even as a translation of crip, but it is also regionally specific, as it departs from discapacidad and the history of that term.

NyZ-R: The [ ] History is a piece of writing, but at times you also stage your research with more poetic agency, or in visual art. Why do you find art a generative field? Or, where do you see the function of artistic practice within the construction, representation, and distribution of scholarly research?

GJ: Art has the potential to be both political and sensitive, by which I mean that it can address things in a way that speaks to intuition and emotion. I believe that when art is relatable, it is a gate toward political consciousness. My early work started as an investigation of my own body, its shape and movement and the spaces where it was allowed to exist. Then I started wondering about others with similar experiences and I turned to the story of my aunt, who had cerebral palsy, to find connections and differences between our experiences of disability.

NyZ-R: Could you please talk more about It’s Like She Never Existed and how that project draws between personal experience and broader historical dynamics?

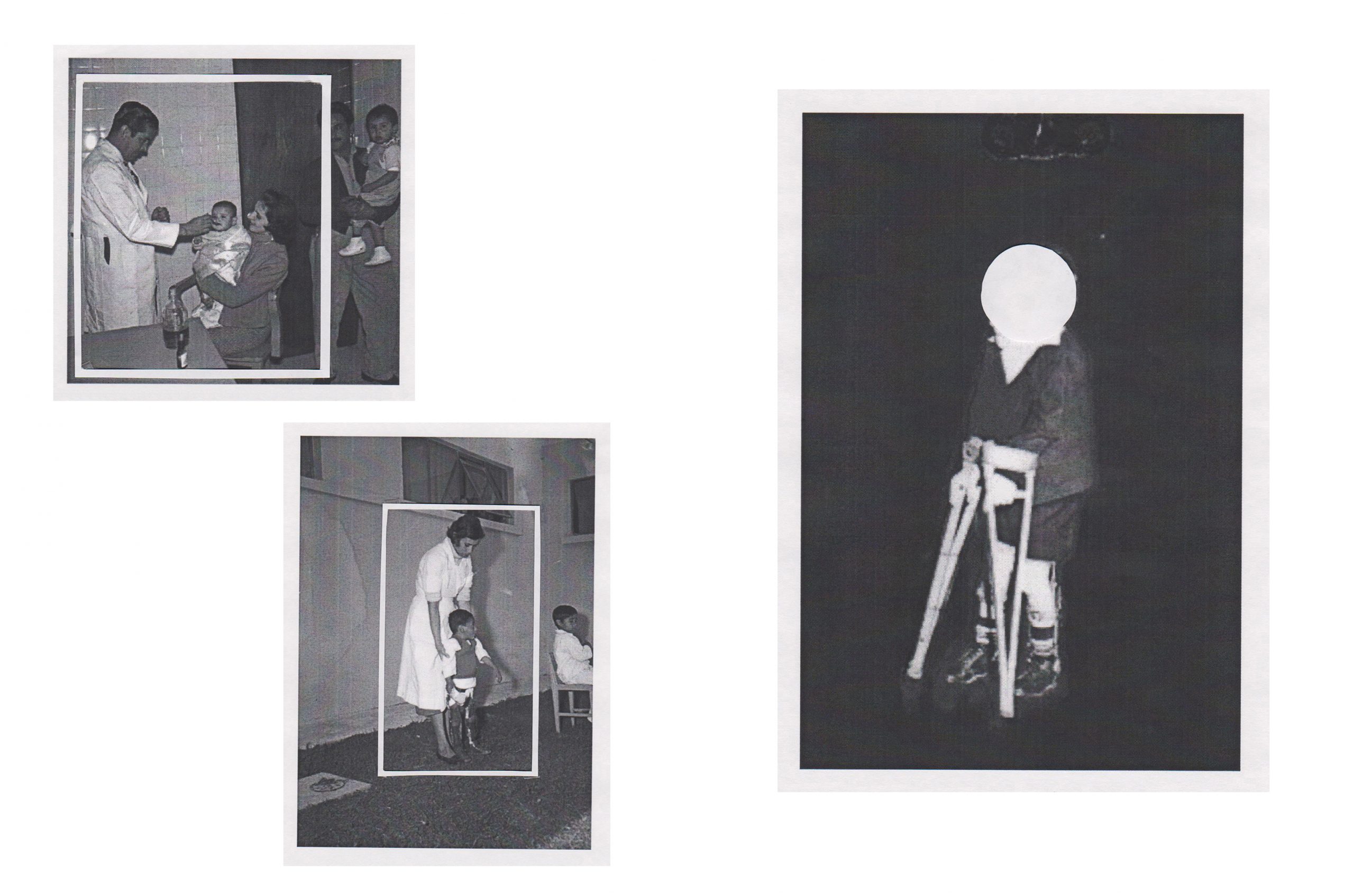

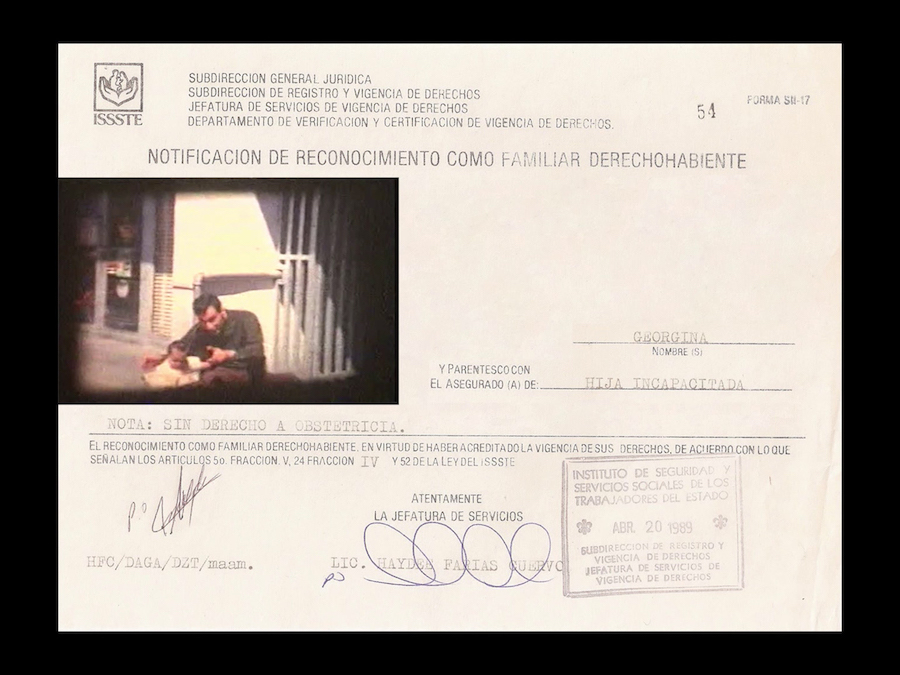

GJ: This project departed from writer and theorist Ariella Azoulay’s concept of potential history, which Azoulay describes as “an effort to create new conditions both for the appearance of things and for our appearance as its narrators, as the ones who can—at any given moment—intervene in the order of things that constituent violence has created as their natural order.” I found myself knowing almost nothing about my aunt and wanted to not only know more about her but also examine why I didn’t know. When working on this project I noticed the different narratives that I was weaving to put together her story: accounts from my family members, images stored in photo albums and film collections, and her personal and medical documents. These different layers helped me connect her life to a wider social context and think of how it influenced the way in which disability was perceived and treated within the family.

GJ: These separate projects are connected by questions of how the Western conception of history is embedded with a narrative of progress. What I found fascinating about Dr. Reinaldo Martinez was that though the “treatment” he tried to validate scientifically was eventually debunked, this “magical cure” he presented reflected the desire for a “less disabled” future, pushed by mainstream institutions and media that portrayed disability as a tragedy. For We Protest Against Polio, I combined real newspaper clippings and photographs with objects I made, like a demonstration banner and medicine vials, into a semi-fictional exhibition. I wanted to develop a potential history from the archived narrative that centered disability instead of the doctor. This work questions the authority of the archive and the validity of historical documents while also asking, what does it mean to protest against a disease?

NyZ-R: Your work, which contends with the historical linkages between disability and disease, are highly resonant today. Has the pandemic shifted your perspectives?

Thinking of disability as a mere bio-physiological trait obscures the big picture and its sociopolitical implications.

NyZ-R: Russell often uses the term cross-disability solidarity. Does this term resonate with you?

GJ: The term disability contains a wide spectrum of body-minds, all with different sensitivities and needs. Access and adaptations (and even theoretical frameworks) that are useful to some won’t be to others. Cross-disability solidarity is the awareness of difference within the difference and the commitment to figure it out. It’s a process that is constantly shifting but to me it’s one of the strengths of disability culture, since it is a practice of building community while acknowledging one’s own strengths, vulnerabilities, and needs.

NyZ-R: Thank you Ana, for your time.

https://open.spotify.com/episode/6t9aZldgIpEZcLMiyrDe7g

Comments

There are no coments available.